It doesn’t matter where it comes from or who plays or what type it is. It’s the mere fact that the music has a quality of people doing it for the sake of doing it.

-Trevor Watts

Over the past five years or so I have been listening to a lot of music from the Northwoods Improvisers, a Michigan free jazz ensemble established in 1976. One of their founding members, bass player Mike Johnston, has been extremely helpful in my education about the Detroit jazz scene, an area on that Big River called Jazz I knew very little about. He recently shared an interesting story about the Spontaneous Music Ensemble (SME).

The first jazz album Johnston purchased was the Polydor 1972 reissue of John Stevens Spontaneous Music Ensemble. This was SME’s third album, originally released in 1969 on the Marmalade label:

He got it in a package along with Keith Tippett’s Blueprint and The Chris McGregor Group’s Very Urgent. Johnston explained:

I was in high school. I then wrote the band (SME) a fan mail letter to some record label address. At the time I think that Julie Tippett may have been playing with the band and also working as their press person. As I recall Trevor told me years later that she gave the letter to him because John (Stevens) didn't like to deal with things like that. So he wrote me back. He also sent me a copy of Amalgam Prayer for Peace and wrote a note on it which I still have… Trevor told me then that my letter in the mid-70s was the only fan mail letter that SME ever received from the U.S.

Through the years, Johnston and Watts developed a friendship. As a result, Watts invited the Northwoods Improvisers to release their first two trio recordings on his ARC label. The first was Fog and Fire, recorded live and released on CD in 1994:

Johnston contributed the nice cover art. This is an impressive debut album filled with lots of youthful fire; however, the long and winding Johnston composition Fog is the most compelling piece. Buy this CD, if you can find it.

When Fog and Fire was recorded in 1976, the Northwoods Improvisers were a total improvising electric garage band. Shortly thereafter they formed a small collective around the idea of playing and taping all live acoustic music. The liner notes state:

Our music is a blend of eastern music, Jazz and collective improvising. This is the first time we have had the chance to release some of our music. We would like to thank Trevor Watts for the opportunity. We hope you enjoy it.

Nearly fifty years later, the Northwoods Improvisers are still active in the Detroit area. Here’s Talon from their latest release Kuhtuhlpa, a live studio recording from August 2011:

This music comes from the same session as the elusive Sagittarius A-Star label’s Primal Waters release and documents the only trio recording of the band after they started playing with Faruq Z. Bey in 2000. To learn more about him, here’s part one of two parts I wrote about him just over a year ago:

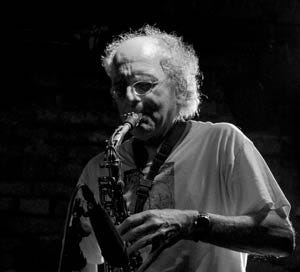

Last week, we explored the world of the SME’s brainchild drummer John Stevens, the one constant throughout the group’s history. In SME’s early years, saxophonist Trevor Watts also played a crucial role.

This week on that Big River called Jazz, our journey is dedicated to the world of Trevor Watts.

Trevor Watts was born in York, England in 1939. He was for the most part self-taught. He played the cornet at twelve and took up the saxophone at eighteen. During his military service in the Royal Air Force from 1958 to 1963, he was stationed in Germany, where he met drummer John Stevens and trombonist Paul Rutherford. After demobilization, he returned to London, and in 1965 with Stevens, he founded the SME, a group that became one of the foundations of the British School of improvisation.

In January 1966, SME began an intensive six-night-per-week residency at the Little Theatre Club in London and the following month recorded their first album Challenge:

In 1967, Watts left the group to form his group, Amalgam. However, he would later return to the SME and remained active until the mid-1970s.

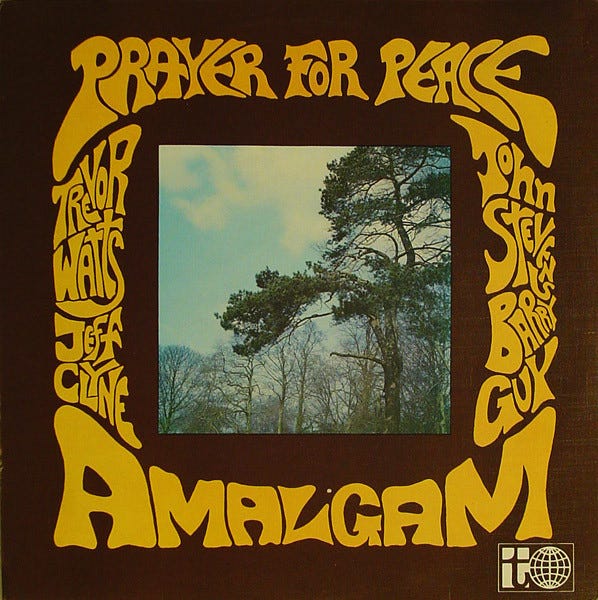

Amalgam was a much more structured group, working under the influence of U.S. avant-garde, European improvisation, and rock. Their first release was the seminal Prayer for Peace, which marked the first time Watts put his music on wax. It was recorded at Advision Studios in London on May 20, 1969, and released by Transatlantic Records:

Amalgam features the trio of Watts, Jeff Clyne on bass, and John Stevens on drums. On the closing, title track Clyne is replaced by Barry Guy, whose warm, buzzing arco bass makes the ideal foil for Watts's mournful Ayleresque melody. Here is the wonderful Prayer for Peace:

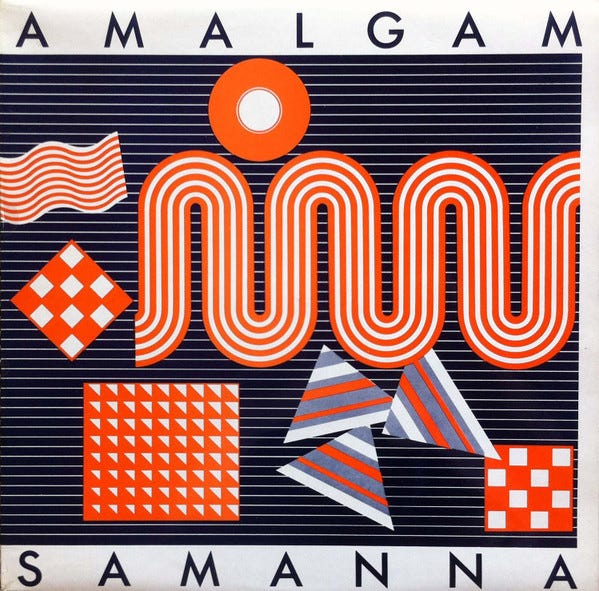

By the mid-1970s the trio had expanded to a quartet and Amalgam’s sound had also changed to a more jazz-rock approach, which you can hear on their 1977 record Samanna:

From this album, here is the rocking Berlin Wall:

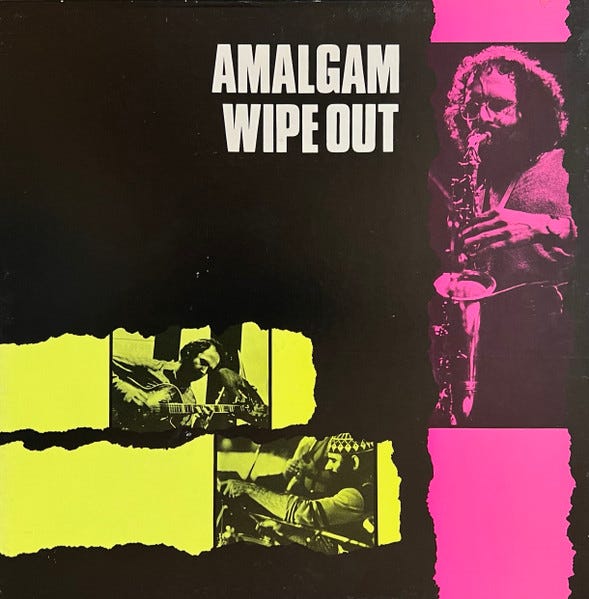

In 1979, Amalgam released their final album, Wipe Out:

This was a 4 LP box set with a booklet sold via mailorder from Impetus Records for 10 pounds. Wow, can you imagine that: only 10 pounds? This release documented Amalgam's final tour.

Also during the 1970s, Watts was part of groups with Pierre Jarre, Bobby Bradford, and Stan Tracey; however, perhaps his important relationship was with Barry Guy and his London Jazz Composers Orchestra, a partnership that lasted from the band's formation in the 1970s until its dissolution in the mid-1990s.

The London Jazz Composers' Orchestra's first album was Ode, composed by bassist Barry Guy and conducted by his teacher, Buxton Orr. It was recorded as part of the English Bach Festival at the Oxford Town Hall in 1972 and first released as a double album on the Incus label - a solid start.

I first heard the London Jazz Composers' Orchestra in the late 1980s, when I was in the service in West Germany. I had been reading about them in The Wire magazine and when their album Zurich Concerts was released, I snatched it up. This is a beautifully produced double live album featuring recordings of two large-scale compositions, one by Guy, and the other by guest artist Anthony Braxton. The Guy work was recorded on November 11, 1987, and the Braxton work on March 27, 1988, both at Rote Fabrik in Zürich. The album was initially released on LP in 1988 by Intakt Records. From that release, here is Polyhymnia:

In 1976, Watts also formed the Trevor Watts String Ensemble and in 1978 the Universal Music Group, but neither group gathered much steam.

In the 1980s, Watts became increasingly fascinated with the fusion of jazz and African music, especially in his group Moiré Music, which he has led since 1982.

Northwoods Improvisers’ Johnston interviewed Watts for an August 1982 issue of Coda magazine, and Watts had this to say about Moiré Music:

I call this group Moiré Music, a French word which is used for watered silk. I think it also means two lines that make up a third… Some of it is similar to a Steve Reich thing, but it’s very different really and it isn’t influenced by him. Primarily it’s got a lot to do with Africa. I think a lot of music Terry Riley and Steve Reich do has a lot to do with Africa, and with jazz and with improvised music in general.

The band’s configuration changed frequently from large instrumental ensembles with a multi-person percussion section to chamber trios. One configuration I like is the Trevor Watts Moiré Music Drum Orchestra. In 1991, that group released a great live album originally on Watts’ ARC label, Trevor Watts' Moiré Music Drum Orchestra – Live In Latin America Vol. 1. It was rereleased in 2013 on CD by FMR Records:

I particularly like Sobira with the Kalimba intro and solid groove throughout.

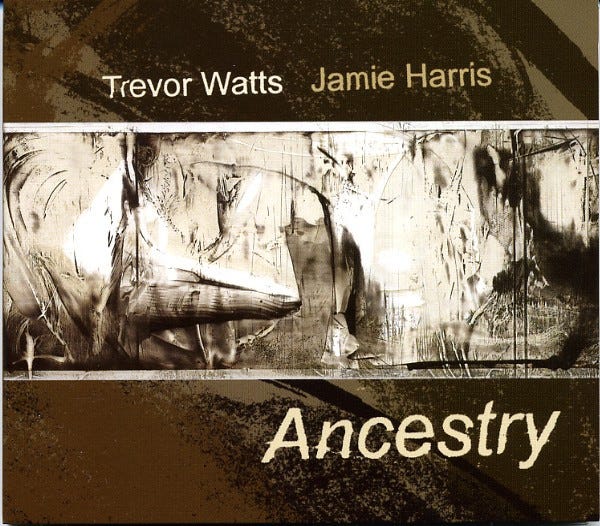

Here’s one more for the road. In 2004, Watts and percussionist Jamie Harris recorded a session that was edited and equalized at ARC Studios in Hastings, England. In 2007, Mike Johnston returned a favor and helped arrange for the session to be released as Ancestry on the Entropy Stereo Recording label, formed in Michigan by Mike Khoury in 1997:

In 2017, Watts and Harris also released an album recorded on May 20, 2005 in Maribor, Slovania:

Although you might not know it since his name isn’t mentioned as often as it should be, Trevor Watts is still performing. In that August 1982 Coda interview, Watts shared this when asked why his music wasn’t reaching people on a large scale:

I think it has got to do with living in England and why we’re not heard even on the continent of Europe let alone in the States or Japan. It also has to do with not leaving this island very often and people not having any actual idea of what we are doing because even if a record does come out it’s only a thousand copies and that’s very small.

In many ways, this is still true. Although many of us are late to the table, the internet has helped us all discover, share, and enjoy his music. When I think about it, I am always surprised that when these albums first came out back in the 1970s someone was hip enough to buy them, like Mike Johnston.

Recently, in a discussion with Johnston, he shared this about Trevor Watts:

For what it's worth I have always loved Trevor’s music. He has always pursued his own direction in music and moved deeply into a world music sound at the same time it was popular for most of the European players to play free music without rhythm. He's a kind person and a great saxophonist.

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of the British label Incus.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….