There are some cultural things that are indigenous to certain areas, and undoubtedly they wear off on the individual, become part of the individual.

-Abdul Wadud

As I look back on our journey, except for our stop to welcome spring two weeks ago, eleven of the last twelve legs of our journey featured Midwest musicians with roots in Chicago (Maurice White, Phil Cohran, two on Eddie Harris, Paul Butterfield, the great Nessa Records, Muhal Richard Abrams, Donald Garrett’s The Sea Ensemble, and Useni Eugene Perkins’ Black Fairy) and Ohio (Chicago’s Idris Ackamoor and the Pyramids at Antioch College in Dayton and Abdul Wadud in Cleveland). The lone outlier was George Russell. Although it was not calculated, I’m sure it was not by chance - after all, I am from the Midwest with midwestern sensibilities.

In retrospect, it does appear as a conscious effort to bring light to jazz happening in places other than New York City and the West Coast. Without the limitations imposed by those scenes, midwestern musicians were able to grow music organically that was in some ways, I feel, deeper and more open. This freedom appeals to me.

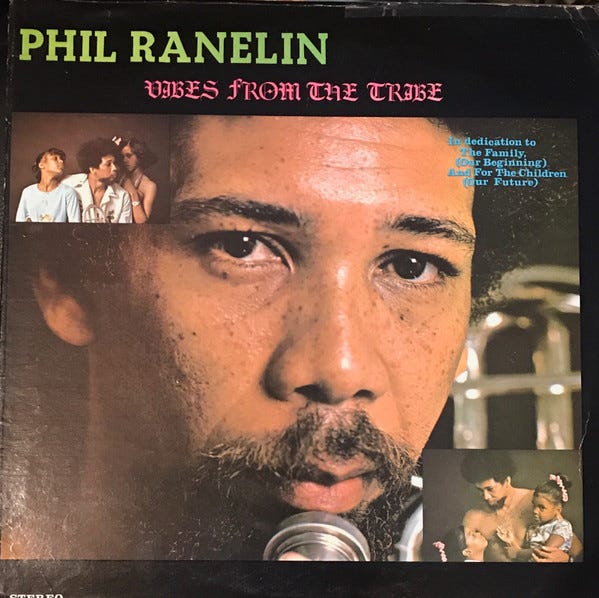

Another midwestern area of emphasis on our journey recently is Detroit (Berry Gordy last November and Joe Henderson last December). Last September, I wrote about the important collective called Tribe, founded in 1972 by trombonist Phil Ranelin, saxophonist Wendell Harrison, and Harrison’s first wife, Patricia. You can read more about Tribe here:

One of my favorite Tribe releases is Phil Ranelin’s Vibes From the Tribe:

The last song on side two is called He The One We All Knew (Parts 1 & 2). It was recorded on September 23, 1975, at Superdisc in Detroit. Along with Ranelin, the track featured an early version of Griot Galaxy with Faruq Hanif Bey on saxophones and congas, Ken Thomas on piano, Ralph Armstrong on bass, Tariq Abdus Samad on drums, and Daud Abdul Kahafiz on sitar. This was Griot Galaxy’s first recorded appearance. Although the band fell apart in 1984, it changed the face of Detroit jazz forever.

Recently, Northwoods Improvisers’ great bassist Mike Johnston shared with me that it’s a mystery why Griot Galaxy never became as recognized as Sun Ra or the Art Ensemble of Chicago. “They were a singular unique ensemble in their own right largely focused around Bey’s compositional selections and concepts. They were a consistently exciting band to see and hear.”

Improvisation is a matter of the truth of the moment - not style. I am inspired by Faruq Z. Bey’s uncompromising honesty and dedication to the spiritual power of music. I hope that he will find greater and more coast-to-coast recognition and with that a much greater appreciation for his wonderful music.

Over the next two weeks on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll explore the world of Faruq Z. Bey and Griot Galaxy.

Jesse Davis was born on February 4, 1942, and raised in Detroit. He started out playing the upright bass and throughout high school studied with jazz scholar James Tatum, who taught in the Wayne County Community College District, Oakland University, and in the Detroit Public School System for more than 30 years. In 1972, St. Cecilia’s church in Detroit commissioned Tatum’s Contemporary Jazz Mass, which he recorded using an ensemble of local singers backed by his trio and local musicians. He released the album in 1974 on his JTTP Records label.

If you listen to Tatum’s Communion, you can get an idea of the music young Davis was hearing and learning:

In 1987 The James Tatum Foundation For The Arts, Inc. was founded by a coalition of concerned educators and civic leaders who recognized that in the Metropolitan Detroit area, there were many artistically talented youth whose potential was not being nurtured to development. I’m not sure if the foundation is still active - does anyone know??

When Davis was 19, he joined the Service. It was in the Air Force that he first considered switching to saxophone saying, “I heard John Coltrane play My Favorite Things on the soprano saxophone. I realized I couldn’t play that on the bass. So I got a saxophone.”

After his military service, he returned to Detroit. Two key events in 1967 moved Bey to finally give up the bass and start studying saxophone. The first was the death on July 17th of John Coltrane. The second, a week later, was the Detroit riots. He told the story that it was while mourning Coltrane’s death during the riots that he had a spiritual epiphany to take up the saxophone.

He studied with Leon Henderson, the creative force behind the Contemporary Jazz Quintet and brother of legendary saxophonist Joe Henderson. If you listen to the Contemporary Jazz Quintet’s Bang!, released by Strata Records in 1973, you can hear the influence it had on Bey’s compositional style:

Leon Henderson was a big proponent of the Schillinger system of musical composition, which was popular during that time at the Detroit Conservatory of Music. Schillinger’s mathematical processes and systematic, non-genre approach to music also had an impact on Bey’s compositional style.

During the post-riot, Black Power time in Detroit, Bey attended a Moorish Science Temple and changed his name to Faruq Z. Bey. In an article he wrote for the Detroit Metro Times, Kim Heron wrote, “He’d [Faruq] become part of an artistic, spiritualist, pan-American, political milieu; he’d eventually become a sort of poster boy for that set.” Here is an early photo of Bey by Leni Sinclair:

Also during this time, he joined a performance ensemble led by tap dancer Aaron Lawson Thompson. In 2004 Bey recalled the ensemble:

We had this thing where we would do poetry. It was like a multimedia thing. We would do poetry and tap dance, we’d play hand drums, saxophones, you know that kind of thing. That’s where I started playing [saxophone]… And out of that, we developed - were trying to develop - as a Sun Ra type of large ensemble. The First African Primal Rhythm Arkestra. It was a very long, and involved name. You know it was one of those total improvisational things.

Bey spun off from this ensemble to form a band he called Griot Galaxy, which by the 1980s emerged as the heavy-hitter Detroit jazz band.

Following the example of a West African storyteller or griot, who spins tales of the past that have meaning for the present and the future, Griot Galaxy tells a story that reminds us of our shared history and at the same time invites us into a very personal, unique world of sound and vibrations. In a WCMU interview with Mike Johnston for his Destination Out radio program, Bey recalled how the group’s name came about:

That was my idea. I had been studying traditional African forms. I read about their African oral historians in West Africa, who were also musicians in the community. The Griots were freer and more open. They were the avant-garde of their community… They had a certain recognition in the community… Being influenced by Sun Ra, we will be the griots of the galaxy - the entire galactic quadrant - we were the oral historians of that.

Throughout these early years, from Tatum’s spiritual teachings to Henderson’s more Schillinger approach, Bey was developing a compositional style that was very unique and multicultural.

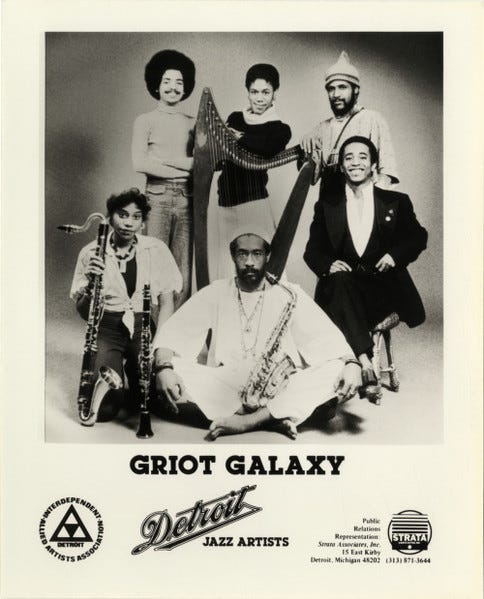

The early Griot Galaxy had kind of a collective feel and revolving line-up until the early 1980s when they settled on a stable line-up that was their most well-known and memorable, consisting of Bey, David McMurray on flute and saxophones, Anthony Holland on saxophones, and an absolute stellar rhythm section with Tani Tabbal on drums, and Jaribu Shahid on bass, who both had worked in the Roscoe Mitchell Sound Ensemble. This later version of Griot Galaxy combined a Sun Ra and AACM-inspired free playing with that Motown groove and pulse that was uniquely Detroit. This powerful Griot Galaxy line-up only released four albums.

In September 1981 they recorded their debut album Kins. It was recorded at Spectrum Sound Studios in St. Clair Shores, Detroit by Ron DeCorte and released in 1982 on his Black & White Records label.

The band was working live then so the music was tight and well-executed, and the cohesiveness came off on the record.

From Kins, here is Xy-Moch Theme:

DeCorte had this to say about recording Kins: “I think it went really easy. We knew each other because we’d been doing recordings at the Detroit Institute of Art (D.I.A.) and various other places around Detroit for a few years prior to that. And so they knew pretty much how I worked and I knew how they worked, and we got in and got everything from start to finish done in what two days, I think.”

In January 1983, Griot Galaxy recorded a live gig at the D.I.A. The recording was released in 2003 on Mike Khoury’s Entropy Stereo Recordings label:

By this time, Bey’s compositions were becoming much more complex. For example, the final track on Kins is Sun Ra’s Shadow World, a sophisticated composition in 7/4 time with lines written in 4/4 and 5/4 time played by the horns. It requires a bassist of the highest order, which Sun Ra had with Ronnie Boykins. Griot Galaxy’s rhythm section of Jaribu Shahid and Tani Tabbal had played with Sun Ra and brought with them the sheet music.

Here’s Sun Ra’s Shadow World from the Arkestra’s 1966 album The Magic City, released on his Saturn label - checkout the complex bass line and the ensemble horn playing at the 3:55 minute mark (this is best listened to on iTunes or Spotify):

Bassist Johnston shared with me that Shadow World, “…is a unique and intricate composition from the era it was first performed by Sun Ra, in the mid-1960s. The lead horn line is complex for that era. Not only intricate but also pushes being a 12-tone composition, which was pretty much unheard of back then.”

On September 4, 1983, at the Stroh MainStage, Hart Plaza in Detroit, Griot Galaxy recorded a couple of songs that were released on volume three of the four volumes of The Motor City Modernists, released in 1984 on the Montreux/Detroit Records label. Here’s a song from that live performance. It is posted as Fosters, a cool Monkish tune Bey wrote about a restaurant he went to a lot for breakfast; however, this tune is not Fosters. Johnston told me, “I don’t know the title of that piece. I spun a live version of it on the radio program as well, and we (Mike Khoury and Kim Heron) mention that we don’t know the title of it. I love the piece.”

Here’s a chance to see Griot Galaxy performing live at the 1984 Metro Times Music Awards. This Jaribu Shahid’s composition Androgeny:

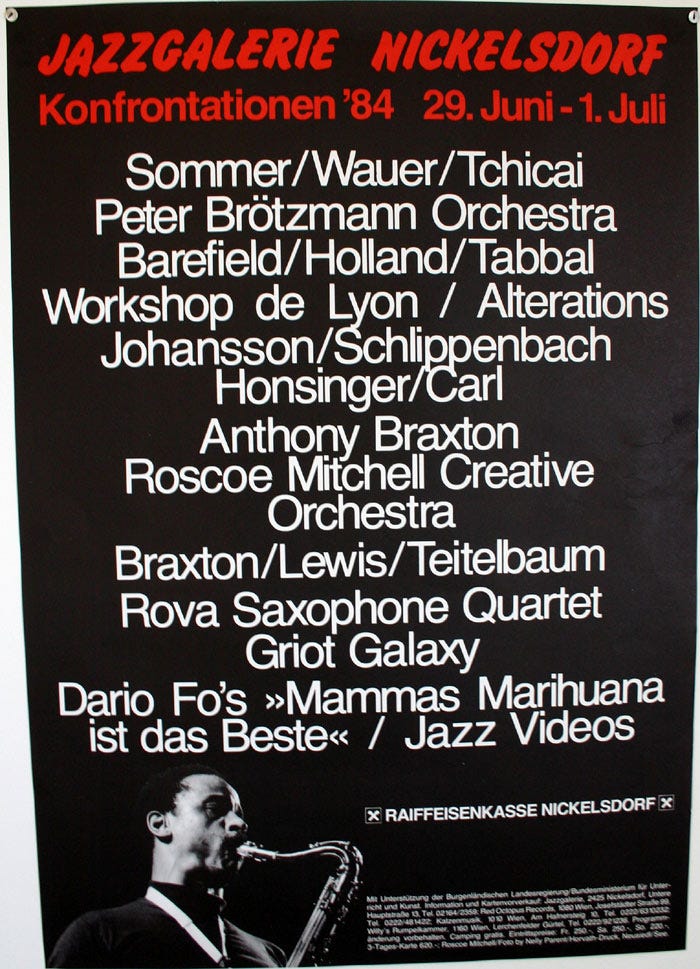

As Griot Galaxy’s popularity grew, they were invited to perform in Europe. Here’s a poster from one of their gigs:

The band’s inclusion with such prominent musicians at the Nickelsdorf Konfrontationen Festival of free and improvised music is a testament to their popularity in Europe.

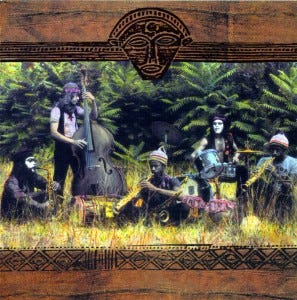

Here’s one more for the road. Their July 1, 1984, live performance at that festival in Nickelsdorf, Austria was captured live. The recording was called Opus Krampus and released in 1985 on Sound Aspects Records. Here’s the album:

Opus Krampus is an excellent opportunity to hear Griot Galaxy in a well-recorded, live session while they were at the height of their success. This is a killer album.

Later in 1984, after returning to the States from their successful European tour, Bey was seriously injured in a motorcycle accident. Heron wrote:

Faruq doesn’t remember the accident itself. He’d left Alvin’s with a young woman riding on the back of his souped-up Yamaha 750 Triple. “Somebody told me it had to do with some railroad tracks,“ he says, “but the fact of the matter was a bad mix of alcohol and motorcycles” His rider was uninjured. Faruq was in a coma at Receiving Hospital for more than two weeks while a circus swirled around him.

While Bey was recovering from his accident, Jaribu Shahid and Tani Tabbal continued to play under the banner of Griot Galaxy with the hot Detroit newcomer James Carter, who had studied under Bey. When Carter hit the big time in New York, Shahid and Tabbal went with him appearing on a number of his 1990s releases, beginning with his debut JC on the Set (1994). Here they are with Carter in the middle on the back of that album:

They also played on Geri Allens’ Open on All Sides in the Middle (1987) and Twylight (1989).

According to Heron, after his accident, Bey came to grips with some of the lessons learned from years of hard living. Bey recalled, “I came away with another knowledge, another knowing about this condition we call life, so I can understand things now that I didn’t understand before about my personal reality and about my social reality, about my cultural and political reality, the reality of my collective past. All of that I see differently now.”

Bey carried that new state of mind into the new century with new groups. In the early 1990s, he played with Synchron and the Lincoln Street Band, with Danny Spencer on drums, who played on Kenny Cox’s Contemporary Jazz Quintet Blue Note records. By the late 1990s, he formed his Conspiracy Wind Ensemble and also had a band with bassist Hakim Jami called Speaking in Tongues. Throughout all this, Bey’s compositional style became even more focused, and I feel more spiritual. By the time he started his collaboration with the Northwoods Improvisers at a small Detroit festival around 1999, he was ready for a fresh start.

Next week, on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles in and explore the world of Faruq Z. Bey’s comeback in the 2000s with the Northwoods Improvisers.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Great stuff! Currently listening to Communion

Another fascinating read, you keep hitting the mark for me with each new post. I know and really rate the Griot Galaxy albums and also Bey with Northwoods and Dennis Gonzalez but the context you give them is greatly appreciated. That James Tatum!