John Hammond

The first time I met the blues...

When I sing, I can stand aside. I can feel good. I can reach people sometimes. I can put so much of me into it and at the same time be made stronger by it.

-John Hammond

The first time I met the blues, I was standing in a room.

In 1969, when I was 7 years old, my dad took me to see the movie True Grit. That was the first time I saw a movie on the big screen in a movie theater. I loved it. But we didn’t go to the movies much. I had to wait for the following year to see another one, which was Little Big Man - that was a defining moment.

Here’s the opening credits of the movie:

At the 50-second mark, the first music you hear is a harmonica. That was the first time I’d ever heard a harmonica, and the spirit of that sound was buried in my soul. That spirit started to find its way out for the first time years later in junior high school listening to John Mayall’s harmonica on The Turning Point, an album in my brother’s record collection. Then in high school, while doing my homework one night and listening to the radio, I heard Come On In My Kitchen, by Robert Johnson. The DJ said it was performed by John Hammond. I had no idea who either one of those guys were. All I knew was that spirit was ready to be set free.

In 1978, John Hammond’s album Footwork came out on Vanguard Records.

The radio station was playing it a lot to advertise Hammond’s upcoming show at a place in downtown St. Paul called Wilebski’s Blues Saloon. I didn’t have my driver’s license yet, so I asked my brother if he would take me.

We drove down by the capitol building, parked, and found the saloon, which looked like a typical old Brownstone. It had a long stairway on the side that took you up to the second floor like we were going to someone’s house. Through the front door was a living room, with beat-up hardwood floors and on the opposite wall a fireplace. There were a couple of closed doors and another area that looked like a kitchen behind an island. In front of the fireplace was a chair, two mic stands, and an amp. Besides us, there were maybe a dozen people and room for a dozen or so more.

After about 10 minutes, the door next to the fireplace opened up, and out walked this guy with two guitars, one made of wood and the other made of steel. He had a rack around his neck. He sat down on the chair, got everything situated, and stuck a harmonica in the rack. Kind of hunched over his guitar and with a slight twitch of his head to the side, he said, “I’m really knocked out to be here in St. Paul.” And then promptly tore into this song, which sounded nearly identical to this:

He was stomping his foot on that wood floor, getting after it, and wailing in a blaze of glory on the harp. The raw emotion of his playing and the overall sound I was hearing was overwhelming. That was the first time I met the blues.

In a strange twist of fate, many years later I would realize that the harmonica I heard at the start of Little Big Man was played by none other than John Hammond.

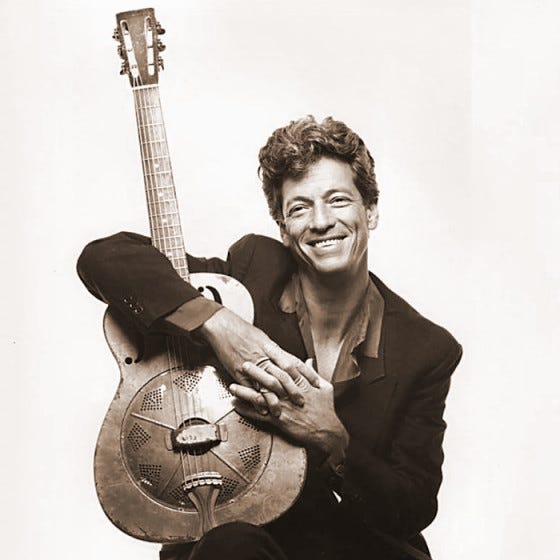

This week on that Big River called Jazz we will explore the world of John Hammond.

John Hammond is the son of the legendary record producer John Hammond, but young John never rode those coattails, saying in a 1970 interview with the Boston-based rock-and-politics magazine Fusion:

People think I've had all these inroads in music because of my father. He's really a spectacular man, and I got to hear the music because of his position. But I've done it all myself. I wanted to be on my own, making my own living, making my own mistakes--and I have been since I was eighteen. In fact, there was a time when my father tried to discourage me from music.

Knowing what his father knew of the record business, I can believe that.

According to the liner notes from young John’s first album, he got his earliest musical learning from the rhythm-and-blues masters, “…guys like Chuck Berry, Larry Williams, Elvis, Little Richard, Jimmy Reed, Bo Diddley.” He first became aware of country blues in high school; he bought a Lightnin’ Hopkins record and “thought it was just the end of the world. I got immediately hung up in it, the fantasy side of it as well as the cold, very tough aspect of it.”

In 1962, after a year at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, Hammond moved to Boca Grande, Florida. He got a job at a hotel as a busman, roomkeeper, and overall handyman. He practiced guitar during his off hours. While busking in town he met a local bluesman Albert McCall, who encouraged him and showed him some tricks on the harmonica. Then he moved to LA for a while and played in the club circuit before heading to Chicago to meet up with some guys he knew, John Koerner and Minnesotan Dave Ray. They drove up to Minneapolis in Hammond’s V-8 Ford and got a job at Matty’s Bar. Then he moved on back to New York City and landed a contract with Vanguard Records.

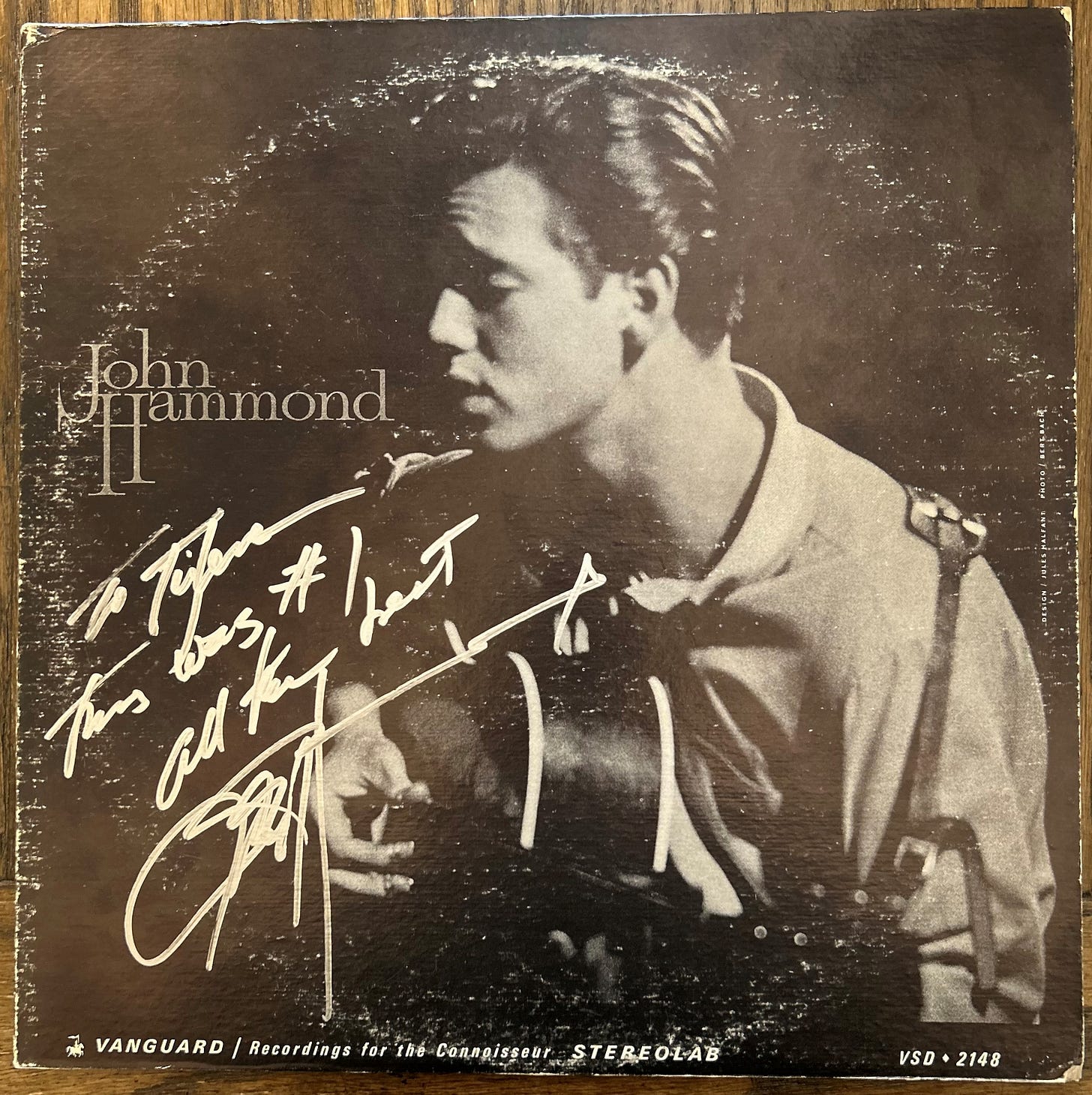

In the fall of 1962, he recorded his debut album:

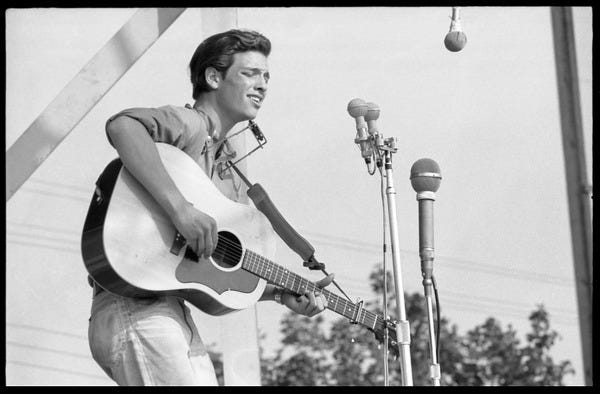

Vanguard didn’t release it until September of 1963 after he was already making a name for himself around New York and performing at the Newport Folk Festival. Here’s a photo of Hammond from July 28, 1963, at the festival:

In January 1964, he got a gig at the Village Gate. This was the same time the Rolling Stones first came to America. According to Hammond, “They came down to dig us at the Gate, and I got to know them, mainly Brian." After the Village Gate, Hammond started touring all over the East Coast and into Canada, where he met a band called The Hawks, who backed Ronnie Hawkins:

At the time Hammond recalls they were “super-straight--crewcuts, immaculate suits, all that. But they were actually totally wild, really far-out cats.” Not long after, they changed their name to The Band and the rest is history.

In 1966 he traveled to England and played some shows backed by bands like Graham Bonds and John Mayall, who had Eric Clapton on guitar. He also met and played with Spencer Davis, who had the Winwood brothers Steve and Muff. When he returned to the U.S. in the summer of 1965 he left Vanguard and signed with Leiber-Stoller. The intention was for Hammond to record an album for Leiber-Stoller’s Red Bird label, and two tracks from the session were released on a 45rpm. Here’s I Can Tell with Robbie Robertson on Telecaster and Bill Wyman on bass:

Unfortunately, the project fell through and was abandoned.

After some time away from music, Hammond returned to New York City and started a new band called The Blue Flames. Hammond recalls,

I met this guy named Jimmy James who was playing stuff off my So Many Roads--he was playing Robbie's parts, but better! I said, 'Wow! I got to get him into the band.' And we also had Randy Wolfe, who calls himself Randy California now (an original member of the band Spirit). And Jimmy James, of course, was in reality, Jimi Hendrix.

We played the A Go-Go and had celebrities digging us every night. Again it was going to happen. But then Jimmy was offered this job in England behind The Animals. He asked me about it, and I told him it sounded like a good thing. The next thing I knew it was The Jimi Hendrix Experience!

In the summer of 1967, Hammond signed with Atlantic and told them about the Red Bird stuff. They acquired and used the tapes on I Can Tell, released in late 1967. Hammond made only two more albums for Atlantic. For the last, they sent him down to Muscle Shoals in Alabama:

The album was released in 1970 and called Southern Fried. It featured some nice guitar work by Duane Allman.

From then on into the 1970s, Hammond toured solo or with a band called His Screamin’ Nighthawks and that’s where I caught up with him in 1978 - the first time I met the blues.

After that show in St. Paul, it would be 15 more years before I saw John Hammond again.

It was about 1993 and he was playing at a grand place called Larry Blake’s on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley. It’s closed now, but I played there from time to time with the wonderful blues singer Jessica Schwartzbauer. She lived on Haight Street in San Francisco. I’d pick her up in my V-8 Chevy and we’d ride over the Bay Bridge to Berkeley. Back in the day, she fronted a Twin Cities band called The Gooneybirds, who opened for Blues Traveler. Those were great times (I miss you, Jessica).

Hammond had recently released Trouble No More on the Pointblank label. This is a tremendously star-studded album featuring the great California band Little Charlie & the Nightcats, formed in 1976 by Charles Baty, who was studying mathematics at the University of California Berkeley, and his friend Rick Estrin. After gigging for years, in 1986 they submitted a tape to Alligator Records, who released it in 1987 as All The Way Crazy. From that album, here is Clothes Line:

Hammond’s Trouble No More also features guest performances by Charles Brown on piano, Roy Rogers on guitar, and Larry Taylor on bass. It also features a stunning Hammond solo performance of Blind Willie McTell’s Love Changin’ Blues:

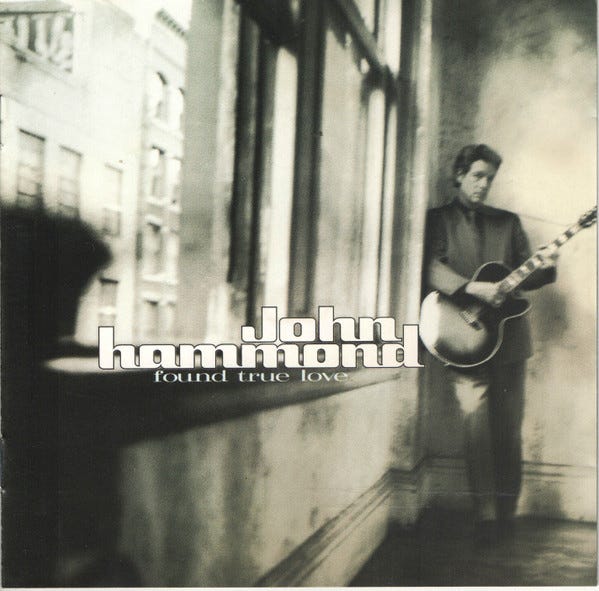

In 1995 Hammond released Found True Love, another powerhouse on the Pointblank label.

Found True Love features one of my favorite guitarists Duke Robillard. Here’s a nice live version from French TV with Hammond and Robillard performing the title track:

For a little more Robillard, check him out playing T-Bone Walker’s classic Glamour Girl:

T-Bone Walker was one of Robillard’s main influences.

Glamour Girl was first released on the Imperial label in 1950. So I think it’s fitting to play a T-Bone version, and I like this one from 1970 with more guitar work:

In 2001, when Hammond released Wicked Grin, I had just arrived in Chicago. I can’t recall where I saw him play, but I stuck around after the show. We talked for a couple of minutes. That was the first time I met him, and it’s not often you get the chance to hang out with your heroes. He was much friendlier than I even imagined.

From Wicked Grin, here is Tom Waits’ song Buzz Fledderjohn with Waits covertly plucking a piano:

From an Austin City Limits broadcast, here’s Hammond playing Tom Waits’ Til the Money Runs Out from Wicked Grin (and stick around at the end for a little teaser of Clap Hands with some sweet harp):

That’s the great Larry Taylor on upright bass, a long-time member of Canned Heat and Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.

In 2007, Hammond recorded the strong Push Comes to Shove with G. Love. From the album here is Sonny Thompson’s I’m Tore Down:

I dig Hammond’s electric guitar work on that one.

In 2010, John Hammond did a solo show at the Dakota in Minneapolis. As ever, he brought it, playing non-stop for about two hours. The show was coming off the heels of his Rough & Tough album, released on the Chesky Records label, produced by David Hidalgo of Los Lobos. It earned Hammond a Grammy nomination. From that album here is Slick Crown Vic:

That was the last time I saw John Hammond; it was a fantastic show.

Here’s one more for the road. The DJ who trained me at KAZU, the radio station in Pacific Grove, was a woman. She had a show called “Blues Across the Bay.” I can’t recall her name, but she was cool and always knew where the best music was playing from Monterey to Santa Cruz. I learned a lot about the blues from her. We shared a love for John Hammond. She played this tune a lot.

Whenever I hear this one I can see her spinning records at the KAZU station.

In that 1970 interview, Hammond shared some interesting insights about where he was at during those hard times when Rock and Roll started to eclipse his style of music. But his struggle was perhaps less about that and more about who he was and what he was playing.

It's hard not to be bitter, but I'm not. I've met and played with so many incredible artists--I've gotten to play with all my idols, John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf. Listen, I shared a bill with the Wolf one time, and he used to call me back out every night. He said, 'Damn, oh you got a lot of heart, John.' A black person can see that I feel what I'm doing--that I'm not just imitating. Because of my family, I've just known so many black musicians in my life. Like my middle name Paul--I'm named after Paul Robeson, my godfather. But it's never been, like, being part of a white group looking on a black culture. I've just been there, so I'm not ill-at-ease now wherever I go. I get hassled more by whites than I do by blacks."

I know all about this. Whenever I mentioned that I liked John Hammond back in the 1980s, folks looked at me funny. They’d say things like he’s a phony or a “blackface” mimic. Man, the critics got it all wrong. In the same interview, Hammond shared:

I began playing because I loved the blues, I loved all these black musicians who are truly great figures in American culture. And I wanted to help propagate, help continue the life of this stuff that was going out of style. I knew I could do it, and I have--I know I've turned a lot of people on to this pure art form, this roots thing of American culture. And a lot of black artists have benefited, so I feel good.

Isn’t that what it’s all about - playing what makes you feel good and not getting hung up in all that other negativity? John Hammond was all about gratitude and keeping the tradition alive. That’s it - need to go no further.

Next week, on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig in our paddles to explore the world of the Duke Ellington.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

Until then, keep on walking….

Great stuff. Thank you! I was blown away by Hammond's steel guitar when i saw him in a Seattle festival in late '90s. Been a fan since. I've thought about the race thing. The shoe doesn't fit with Hammond like it does, say, with Zeppelin. He's the real deal. He absorbed his upbringing and influences and plays with authenticity that few others can match. The man is the blues, straight up.

Thanks for this, Tyler! Hammond is one of those guys who I keep forgetting about. I mean, I love hearing him play, but I always pick something else to listen to until the next time and then I say “why don’t I listen to more John Hammond?”

So thanks for bringing me to another John Hammond period.