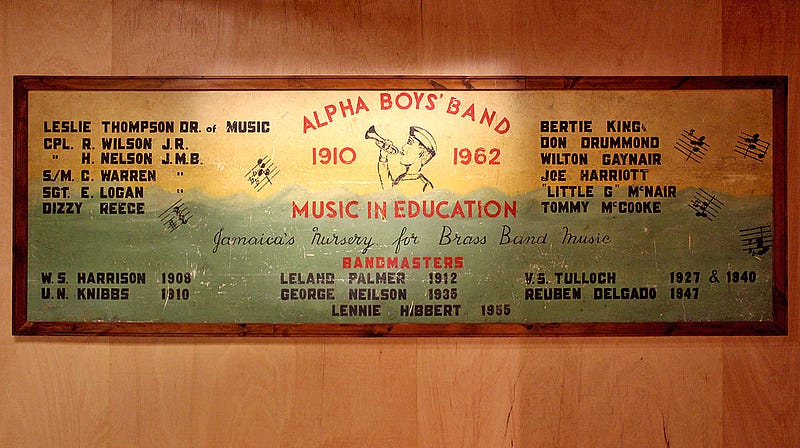

This sign features many of the fine musicians we have covered on our journey over the past month, including Don Drummond, Tommy McCook, Harold McNair, and Dizzy Reece. This week, we’ll cover two more: Wilton Gaynair and Joe Harriott.

We’ll spend the bulk of our journey following Joe Harriott; however, before we start down that river, we need to cover the backwaters of Wilton Gaynair.

After attending the Alpha Boys School, Gaynair began his professional career playing in Kingston clubs. In 1955 he traveled to Europe and landed in Germany in search of opportunities. He recorded only three times as a bandleader, two of these in the late 1950s with the British label Tempo. His first, Blue Bogey, is an outstanding debut album produced by Tony Hall. Recorded in London in August 1959, here is Deborah:

He returned to Germany and remained there for the rest of his life playing as a session musician and with the Kurt Edelhagen Radio Orchestra. As a member of that orchestra, he played at the opening ceremony of the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich.

From a short video from 1966 with Kurt Edelhagen’s band in Berlin, here’s a great chance to see Gaynair playing a composition he wrote You Shouldn’t:

Also of note, the trumpet solo at the start is played by another Jamaican musician, Shake Keane, who played on Joe Harriott’s seminal Free Form and Abstract albums - we’ll cover those a little later. With this in mind, we’ll jump into the river of Joe Harriott.

Sonny Boy Williamson recorded Don't Send Me Flowers at the legendary IBC Studios in London on January 28, 1965. It was released on the Marmalade label in 1969. His sidemen for this session included heavyweights Jimmy Page and Brian Auger. A song on the album, I See A Man Downstairs, is actually Elmore James’ One Way Out. James’ song is not only covered here by Williamson but also served as the basis for John Mayall’s Room To Move on his 1970 The Turning Point and was covered by the Allman Brothers Band on their 1972 Eat A Peach.

Here is I See A Man Downstairs:

This song might be most known for Jimmy Page’s guitar solo and then perhaps for Brian Auger’s organ. However, what’s most notable to me is the sax solo by the Alpha Boys School’s own Joe Harriott.

Joe Harriott was born in 1928 in Kingston, Jamaica. He entered the Alpha Boys School on July 6, 1938. He was 10 years old and looking to receive a music education. He was taught and nurtured there by the Sisters of Mercy. From what was gathered from oral accounts, his mother died while he was quite young. Before she died, she asked that her daughters be placed with their aunts, but that her sons be entrusted to the “Catholics” for their upbringing.

He graduated from the school in 1945 and played in the Jamaican big swing bands of Jack Brown, Eric Dean, and The Jamaican All-Stars. He also played in a trans-Atlantic cruise ship band in 1951 that led him to the UK and finally to London, where he lived for the rest of his life. In London, Harriott worked freelance and in Pete Pitterson’s band. In 1954, he played with the popular Tony Kinsey Trio and also with Ronnie Scott’s big band.

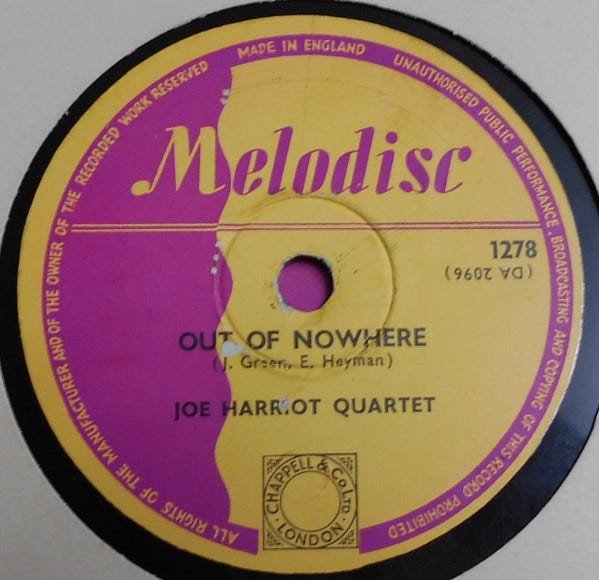

In February 1954, he recorded his first session as a leader on the London Melodisc label:

This is an interesting label that released the classic Mambo Contempo, by Nigerian percussionist and bandleader Ginger Johnson:

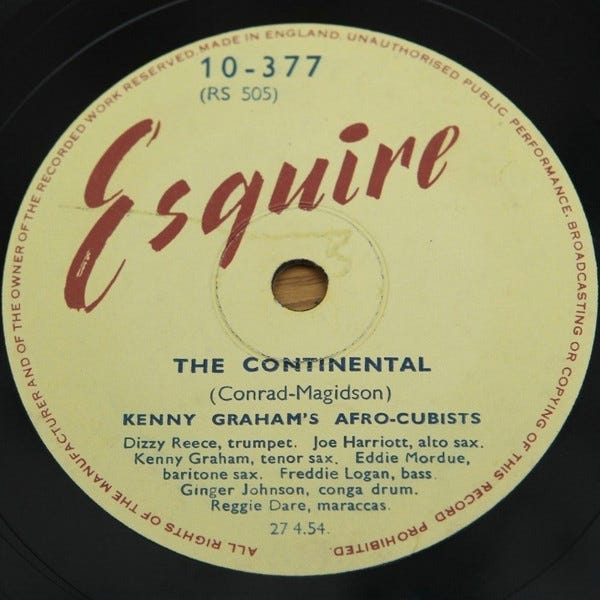

On April 27th, 1954, Harriott would join Johnson on another date with Kenny Graham's Afro Cubists. That Esquire session also included Harriott’s countryman trumpeter Dizzy Reece, who we covered on last week’s journey.

As a side note, Kenny Graham is an interesting character, who in 1956 with his band Kenny Graham and His Satellites recorded an album on MGM Records called Moondog And Suncat Suites. Released with a Miro painting on the cover, it contains an interesting side of Sun Ra-esque music allegedly inspired by private tapes circulating in jazz circles of Moondog’s music and a less interesting side of a straight-ahead six-song suite Graham wrote as a companion piece.

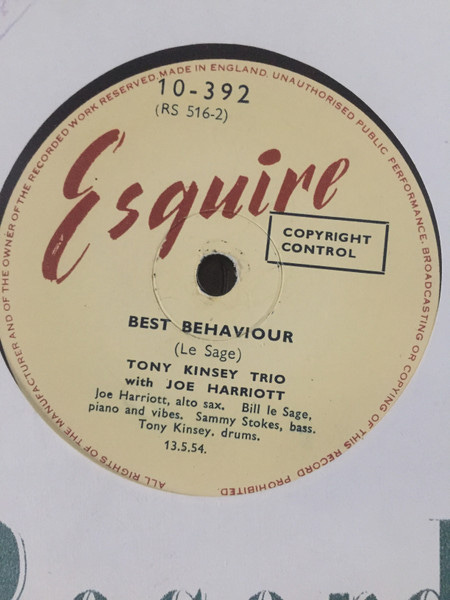

In May 1954 Harriott recorded another session for Esquire, this time with the Tony Kinsey Trio:

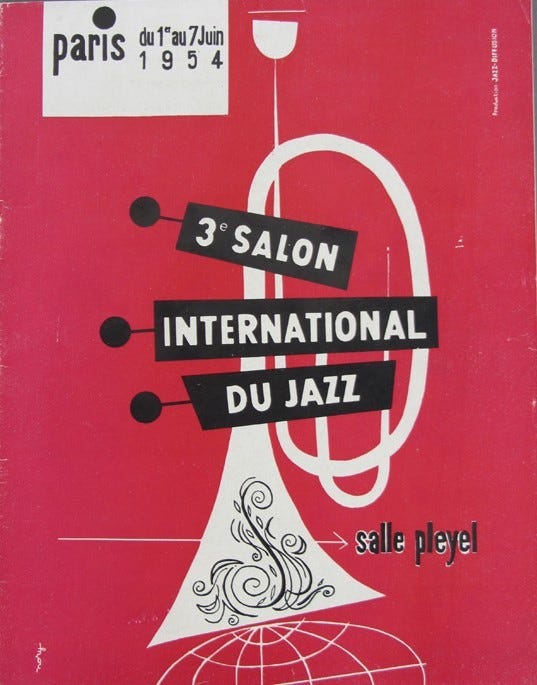

In June of 1954, he traveled to Paris with the Tony Kinsey Trio to perform at the third annual International Jazz Festival at the Salle Pleyel in Paris:

This is the same concert that featured among others the Gerry Mulligan Quartet and Thelonious Monk, who made his European debut on the festival's opening night.

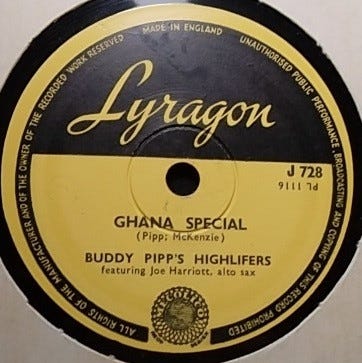

In the autumn of 1954, back in London, Harriott recorded some nice sides with Buddy Pipp's Highlifers on the short-lived UK Lyragon label that specialized in calypso and jazz music and was among the first recordings of African music in Britain:

Harriott is featured here on Pipp’s Ghana Special:

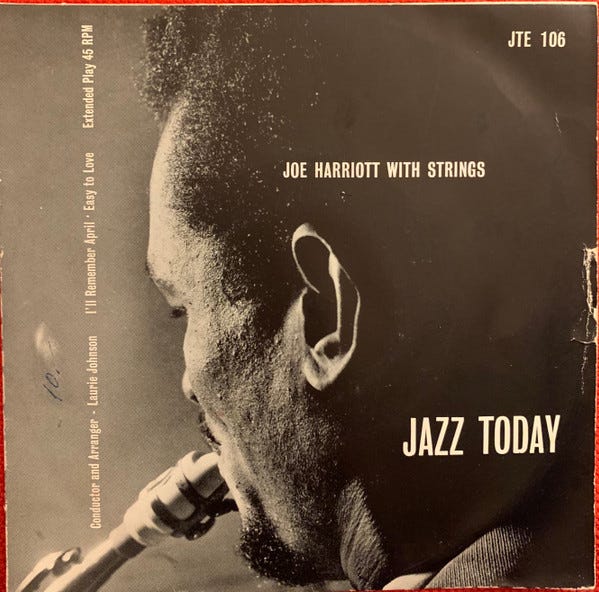

In May of 1955, Harriott recorded again as a leader on the Jazz World label, released as the Parker-esque sounding 45rpm EP Joe Harriott with Strings:

…and the following August on the Nixa Jazz Today Series label as another 45rpm EP, this time with No Strings:

On the strength of these releases, by the late 1950s, Harriott established himself as one of the top alto players on the London jazz scene.

In 1957, Harriott recorded with the Tony Kinsey Quintet on the Decca label. The album was recorded at the Railway Arms “public house” next door to the Decca studios in front of a private audience of “Jazz at the Flamingo” club members:

From the album here is Just Goofin’, a smoker with Harriott playing over 20 choruses:

This is a good example of Harriott’s playing while he was beginning to move beyond his Parker influence to explore the more free-form style he developed the following year with his innovative quintet.

On November 17, 1959, after the release of his The Shape of Jazz to Come, Ornette Coleman and his quartet started a residency at the Five Spot in Greenwich Village. At the same time, another Free Jazz combo was playing in London. According to John Litweiler in his book The Freedom Principle, “This was the experiment-minded quintet of Coleman-inspired altoist Joe Harriott. They played some pieces without pulse, others in freely moving tonalities, and even at their most conservative they used freely modal settings at the least.”

Harriott released two albums with this innovative quintet: Free Form and Abstract. His quintet on both albums consisted of Harriott on alto, Shake Keane on trumpet, Pat Smythe on piano, Jamaican Coleridge Goode on bass, and Phil Seamen on drums (Bobby Orr also recorded 4 sides on Abstract).

For example, from his album Free Form, recorded in November 1960, here is the song Abstract:

In two sessions from November 22, 1961, and May 10, 1962, in London, Harriott recorded the seminal album Abstract. It was released in 1963. This is a masterpiece. At the time Coleman released Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation, Harriott was developing a parallel style that featured perhaps more of a collaborative improvisation and the more obvious addition of a piano.

It’s difficult to choose one track from this classic album, but here is Pictures:

This album deserves multiple listens to appreciate the depth of its beauty. As the cover points out, it was indeed revolutionary.

On the back cover of Abstract, Harriott wrote:

So far as my own Free Form music is concerned…hardly a writer has come to me to try to find out exactly what we are trying to do. Instead, they have used conventional yardsticks to measure a commodity of which they know nothing….

[The music] is best listened to as a series of different pictures - for it is after all by definition an attempt to paint, as it were, freely in sound…And the fan who came up to us after listening to a number at a date in Liverpool to complain that the music “didn’t swing” had better listen again; it wasn’t meant to swing!

In his epic book Forces in Motion, Graham Lock tells how Anthony Braxton remarked after reading the back cover from Abstract: “Braxton hands back to me the (cover) with a sigh. ‘Plus ça change,’ he mutters, staring gloomily out the window. ‘Plus ça change.’”

Here’s one more for the road. I think one of Harriott’s most beautiful performances is on Hum Dono, his album with Amancio D’Silva, recorded in London in early 1969 for the Columbia label. From that album, here is Ballad For Goa:

Unfortunately, this would be his last album. Joe Harriott passed away in early 1973. He was just 44 years old. He is buried in a churchyard in Southhampton, England. His gravestone reads his often-quoted expression, “Parker? There’s them over here can play a few aces too….”

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the deep and wide waters of Italian film soundtracks.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel so inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Love this one as well & still absorbing & listening to the clips. I had read about ‘Bogey Gaynair’ during my early days listening to Reggae but never really heard him. Also heard Joe Harriott a little but wasn’t exposed as a teenager when I started listening to hard bop & Trane & Monk to the European tributary. So I’ve been catching up as an adult.