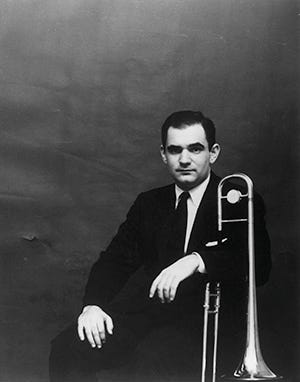

William Russo

New concepts of Jazz artistry....

I was a blues guy long before I was ever a jazz guy.

Throughout high school, I was obsessed with the blues. I had started playing the harmonica in 7th grade. Way before I ever played When the Saints Come Marching In, I was playing blues licks. I started playing along with popular rock songs that had harmonica parts in them, like Doobie Brothers’ Long Train Running, Journey’s Departure, and J. Geils Band’s Wammer Jammer. Then I started to just play along with blues tunes like ZZ Top’s Blue Jean Blues. But mostly I played along with John Mayall records. My first live performance was as a guest harp player with the group called Sonfire at the Fitzgerald Theater in St.Paul. I remember that night meeting Garrison Keillor, who told me he liked my harp playing.

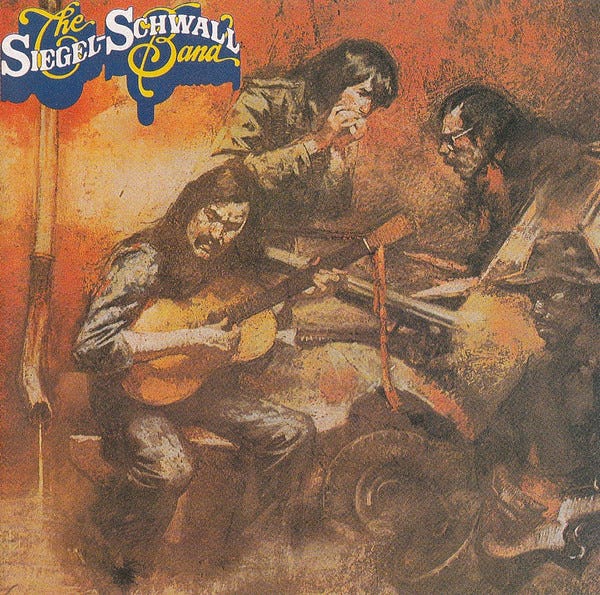

When I was in junior high school, I’d go to the White Bear Lake public library and check out blues albums. It was here that I learned a library could be a good source for great music - a precursor to “Ground Zero”. One album I recall liking a lot was The Siegel-Schwall Band:

I listened to Corky Siegel play harp on Jimmy Reed’s Hush Hush probably a million times. I tried to play along with it and that song was really my early harp education. An interesting side note on this album is the band’s bass player is Rollo Radford, who would go on to join Sun Ra’s Arkestra in 1982.

So in 1980, my senior year in high school, when I saw that Corky Siegel was playing at Orchestra Hall in St. Paul, I bought a ticket and went. Here is the first song they played that night:

Wow. A harmonica with a symphony. This was all altogether different to me and remains a special moment in my jazz journey. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was listening to a composition by William Russo.

William Russo grew up in Chicago and attended Senn High School, where he met Lee Konitz. In 1943, both Russo and Konitz studied with the great Lennie Tristano at the Axel Christensen School of Popular Music in the Kimbell Building on South Wabash Avenue. During summer vacations, Russo played trombone in the Orrin Tucker and Clyde McCoy bands. In college, he assembled his first rehearsal big band, the Experiment in Jazz Orchestra, which played concerts in the Chicagoland area. Russo’s band recorded two 78rpm records at Universal Recording Studio:

According to Russo, “Pete Rugolo had heard about the Experiment in Jazz Orchestra I was leading in Chicago and came to hear us. He invited me to a concert they (Stan Kenton’s band) were playing that night and there he introduced me to Stan. I was just 20 years old, Kenton was the biggest jazz name in the country, and I am sure I was quite overcome by hero worship that night. I had no idea that a couple of years later he would be calling on me to join as trombonist and arranger for the band.”

William Russo’s first arrangement for Stan Kenton was Solitaire, which appeared on Kenton’s Innovations in Modern Music album, released in 1950 on the Capitol label. I love Milt Bernhart’s trombone solo, which besides his solo on Frank Sinatra’s I’ve Got You Under My Skin is his most widely heard trombone solo:

About Solitaire, Russo recalls: “I had never studied composition, except through listening and reading scores and books, and I am unable to explain how I came to compose this piece, which is filled with strangenesses that I no longer know the secrets of. Stan and Pete Rugolo encouraged me to play the solo trombone part, but I declined; I lacked confidence as an instrumentalist and I had great admiration for Milt Bernhart’s exquisite playing.”

Kenton’s Innovations band was stacked with great talent, along with Bernhart there was: Art Pepper, Bud Shank, Bob Cooper, Shorty Rogers, Laurindo Almeida, Don Bagley, Shelly Manne, and June Christy, to name just a few.

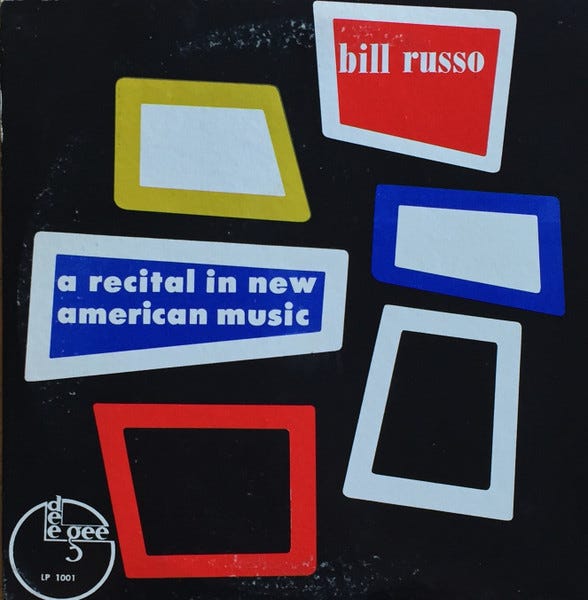

In 1951, during his second year with Kenton, Russo came to the attention of Dave Usher of Dizzy Gillespie’s Dee Gee Records which resulted in a ten-inch LP for that label, A Recital of New American Music.

Most of the material on this record was written for two concerts entitled Pulse ‘51 performed with essentially the same band at Chicago’s Kimball Hall on 25 E. Jackson Blvd. in Chicago.

In 1952, Russo wrote Frank Speaking for Kenton’s New Concepts of Artistry in Rhythm album:

Here’s what Russo recalls about Frank Rosolino, for whom he wrote the song: “When he first became known in the 1950s, Frank Rosolino opened up the technique of trombone playing. We were all staggered by what he could do, not only at the speed of his technique and that he played so well in the upper register, but that he could move from one note to the other so smoothly and effortlessly and that he could play over the entire range of the instrument with ease and with evenness of tone.”

However, Russo would leave Kenton in the mid-1950s, and like Rugolo and Holman, I think his best work happened after he left the Kenton band.

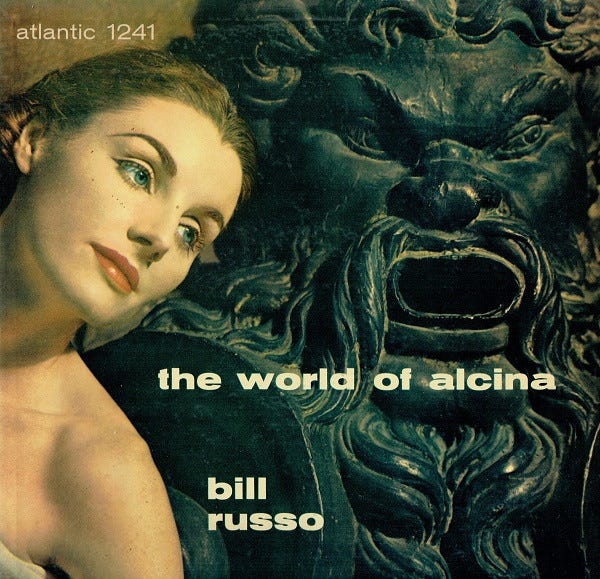

After Russo left Kenton in 1954, his interest moved quickly toward a fusion of jazz and classical music. This transition can easily be heard in his jazz ballet The World Of Alcina, recorded on the Atlantic label in 1955:

About The World Of Alcina, Russo says, “The idea of writing ballet first occurred to me in 1953. I wanted to write a work in jazz terms - or at least derived from my background in jazz. In addition, I felt that the music should precede the choreography and that the storyline for the work should precede both.”

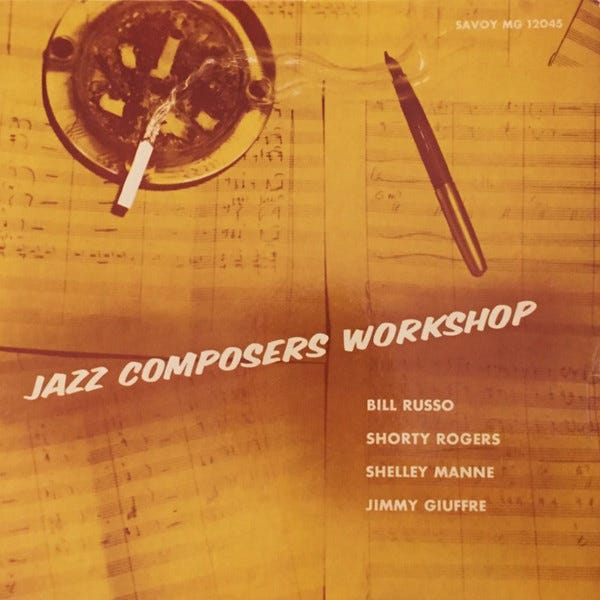

In 1955, he recorded a nice album on the Savoy label, Jazz Composers Workshop. Russo shared the album with a couple of compositions by Shorty Rogers and Shelly Manne, but Russo was the main attraction, supplying 6 of the 14 compositions.

You can listen to the whole album here, but I really like the last song on side 2, Russo’s arrangement of Shelly Manne’s Vignette - go to the 36:45 minute mark to find it. This song has a Chicago melancholy feel that appeals to me. It’s the type of song that gets better each time you hear it.

In 1958, Russo moved to New York City and wrote Symphony No. 2 in C, Op. 32 "Titans". He wrote the music for Leonard Bernstein, the New York Philharmonic, and trumpeter Maynard Ferguson. Although never commercially recorded, the premiere performance is available on the New York Philharmonic's website.

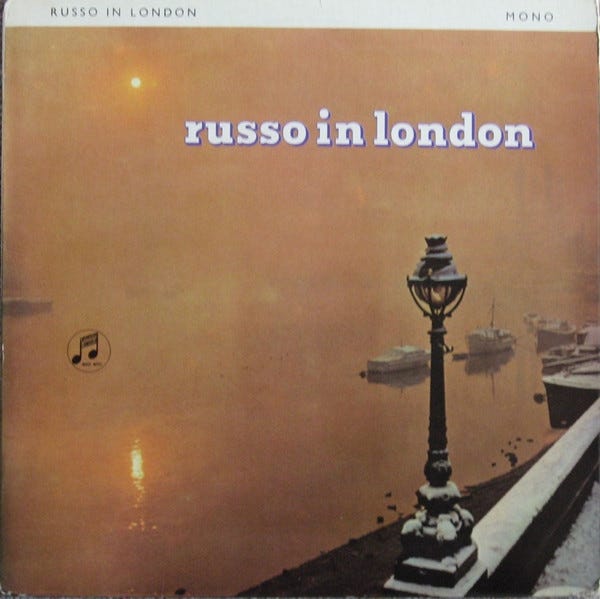

In 1962, Russo moved to England to work for the BBC. While there he founded the London Jazz Orchestra and in December of 1962 recorded Russo in London.

I love the song Suite No. 1 Opus 5: IV Thisbe (to Max Jones), which has a Chicago sensibility that I feel when I listen to it:

Beautiful oboe solo near the end by Richard Morgan. The album has a Gil Evans feel to it that I like.

In 1965, He moved back to Chicago and founded the music department at Columbia College.

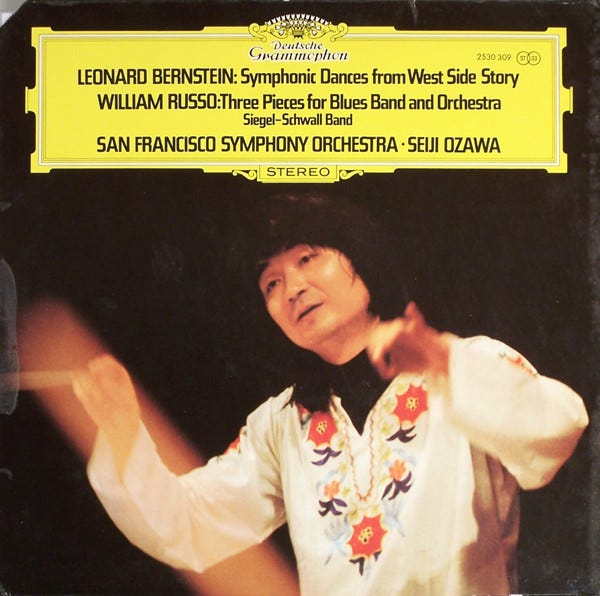

In 1968, he wrote Three Pieces for Blues Band and Orchestra, which was the first Symphonic blues performance, featuring classical music played by an orchestra and blues music played by the Siegel-Scwall Band, a four-piece blues band.

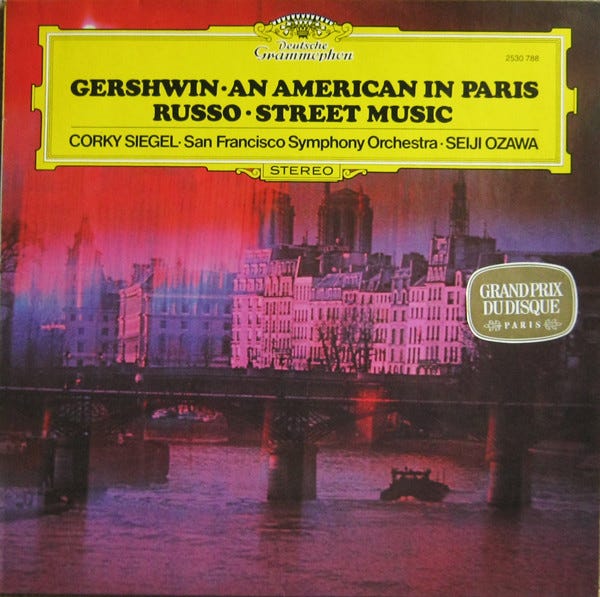

Three pieces for Blues Band and Symphony was recorded in 1972 on the Deutsche Grammophon label. This performance was conducted by Seiji Ozawa.

Seiji Ozawa served as the musical director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra for 29 years.

From 1964 through 1968, Ozawa also served as the first music director of Chicago’s Ravina Festival, the summer home of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. In 1966, as legend has it, after a night rehearsal for his spring concert with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, someone brought Ozawa to Big John’s. At that time, Big John’s was the only spot in Chicago where the city’s world-famous blues bands played regularly before white audiences. Corky Siegel and Jim Schwall started at Big John’s as the Monday night fill-in gig and by the summer of 1966 were hired for full weeks. The second time Ozawa came to the bar, Ozawa had the idea to include the Siegel-Schwall Band in one of his orchestral concerts.

The following year, Ozawa selected and conducted Russo’s Symphony No. 2 “Titans” at Ravina. A few days later, Russo sent an agent to Ozawa to propose a “blues concerto” project that would employ the Siegel-Schwall Band in an orchestral work. Ozawa agreed and the Illinois Art Council commissioned Russo to write the score. The work was first performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Ozawa, and the Siegel-Schwall Band at Ravina on Sunday afternoon on July 7, 1968. In 1972, the work was recorded for Deutsche Grammophon by the San Francisco Orchestra under the direction of Ozawa:

I find the music of Three Pieces for Blues Band and Orchestra interesting conceptually; however, his Street Music, Op. 65 (A Blues Concerto) composition is far superior, which featured just Corky Siegel on harmonica.

In 1975, Street Music was first performed by Siegel and Ozawa, with the San Francisco Symphony. A recording of this piece was released in 1977, again on the Deutsche Grammophon label.

Russo’s Street Music is a seminal composition and really a one-of-a-kind work of art. I encourage you to take some time and listen to the entire concerto.

In 2000, I had the pleasure of seeing William Russo at the Jazz Showcase in Chicago conducting the Chicago Jazz Ensemble performing The Music of Stan Kenton. It was a wonderful evening of music and a great chance to see one of Chicago and America’s great composers and arrangers work. It was also one of the last shows I would see in Chicago, as my family and I moved to Minnesota in the spring.

Here’s one more for the road. Recorded in October 1951, this live recording of Russo’s Ennui is a masterpiece and an excellent opportunity for the soloist, in this case Harry Betts, to explore the possibilities of the often neglected trombone.

Next week on that Big River called Jazz we’ll stay in Chicago and dig our paddles into the music of Lennie Tristano.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button at the bottom of the page. Also, if you feel so inclined, become a subscriber to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe” button here:

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….