V-Disc

The American military record label....

“This is Captain Glenn Miller speaking for the Army Air Force's Training Command Orchestra, and we hope that you soldiers of the Allied forces enjoy these V-Discs that we're making just for you.”

- Glenn Miller’s introduction to “Stardust” on a December 1943 V-Disc recording

In 1942, at the peak of his career and popularity, 38-year-old Glenn Miller joined the war effort. Too old to enlist and after the Navy rejected his request to volunteer, he sent a letter to Army Brigadier General Charles Young requesting to “be placed in charge of a modernized Army band.” Finally, the Army accepted the request, and he was commissioned as a captain in the Army Specialist Corps. He soon became the leader of the Army Air Force Band.

Tragically, on December 15, 1944, an army airplane carrying Glenn Miller vanished over the British channel. He had been on his way to Paris, arranging for his band to play some shows for American GIs stationed in Europe.

In 2007, Charles Munoz, who at the time of Miller’s disappearance was serving overseas in the Navy, shared this recollection:

My own navy torpedo bomber squadron was then training in Hawaii. I remember that every night we played a 78rpm ten-inch record of this music, Taps Miller, in our ready room in honor of Miller for perhaps a month. Nothing formal -- it was simply something we wanted to do...and this was the kind of music we liked.

Here is the V-Disc he was speaking of, Count Basie’s Taps Miller, recorded on January 11, 1945, and released on V-Disc in April 1945, just four months after Glenn Miller disappeared:

I find this recording among the best of Basie 1940’s band. Basie’s soloists in order are Jimmy Powell on alto sax; Buddy Tate on tenor sax; Harry Edison on trumpet; Dicky Wells on trombone; Lucky Thompson on tenor sax; and Rodney Richardson on bass. I really like Lucky Thompson’s tenor on this song.

Disclaimer on all the V-Disc recordings featured on this week’s journey: The recordings are taken off original 78rpm V-Discs rather than masters or later LPs or CDs, so the defects you hear are right off those records, which I think adds a little nostalgia to our journey.

I don’t recall ever seeing a V-Disc until a few years ago. I was reading Lestorian Notes by Piet Koster and Harm Mobach and noticed that, while playing in Count Basie’s Orchestra, Lester Young had recorded some songs on the V-Disc label. I then remembered seeing a large collection of V-Discs at a local record store. So I went back to check them out.

While thumbing through all these beautiful 12-inch 78rpm V-Discs searching for Lester Young recordings, I also noticed a plethora of other great bands and artists. For example, I picked up V-Discs by Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday, Claude Thornhill, and Duke Ellington, some of which are featured in this week’s journey. However, I still did not know the story of V-Disc recordings….

The V-Disc program was an initiative to produce several series of recordings during WWII by special arrangements between the U.S. government and various private U.S. record companies. The recordings were created for the Army between October 1943 and May 1949 and for the Navy between July 1944 and September 1945. The program actually started in 1941, six months before the U.S. involvement in WWII. It was the brainchild of Captain Howard Bronson, who was assigned as a musical advisor to the Army’s Recreation and Welfare Section. He thought the program could motivate soldiers and improve morale.

In 1942, Bronson sent to the troops Armed Forces Radio Services (AFRS) 16-inch 33rpm shellac transcription discs. These discs contained commercial-free radio broadcasts, film soundtracks, and special recording sessions and concerts. Unfortunately, four out of five discs sent overseas arrived in pieces, a similar fate as the vast majority of standard shellac 78rpms sent over to soldiers from their families and friends. Regardless, the project did show promise.

On August 1, 1942, not even a year since America entered the war on December 8, 1941, the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) union president James Petrillo declared a strike against the major American record companies around disagreements over royalty payments. As a result of the strike, no union musician (virtually all jazz and swing musicians at the time) could make recordings for any commercial record company. The strike lasted two years and had a major impact on the American music scene that is well beyond the scope of this week’s journey. However, from this strike was born the V-Disc program and no other person was more responsible for this than sound recording pioneer George Robert Vincent.

G. Robert Vincent had fought in WWI as a 17-year-old lieutenant. He later worked with Thomas Edison, designing phonograph recording improvements.

By 1942, he was assigned to the Armed Forces Radio Service as a technical officer and worked with Bronson on the 16-inch transcription disc project.

In 1943, Vincent intervened in the musician’s strike and convinced Pertillo to allow for the establishment of the V-Disc program, for which he was later awarded the Legion of Merit. Incidentally, Vincent served as a Sound Recording Officer at the Nürnberg Trials after the war.

According to the Save The Vinyl website:

The American Federation of Musicians, under the leadership of James Caesar Petrillo, were involved in a major recording ban against the four major record companies. This continued until the intervention of recording pioneer George Robert Vincent, who was at that point a lieutenant. On October 27, 1943, Vincent convinced Petrillo to allow his union musicians to record sides for the military, as long as the records were not offered for purchase in the United States. From that moment on, artists who wanted to record now had an outlet for their productivity — as well as a guaranteed, receptive, enthusiastic worldwide audience of soldiers, sailors and airmen. (The "V" stands for "Victory" although Lieutenant Vincent was quoted later to say that the "V" stood for "Vincent)".

Perhaps the biggest reason for the success of Vincent’s V-Disc program was finding a suitable alternative to shellac: vinyl.

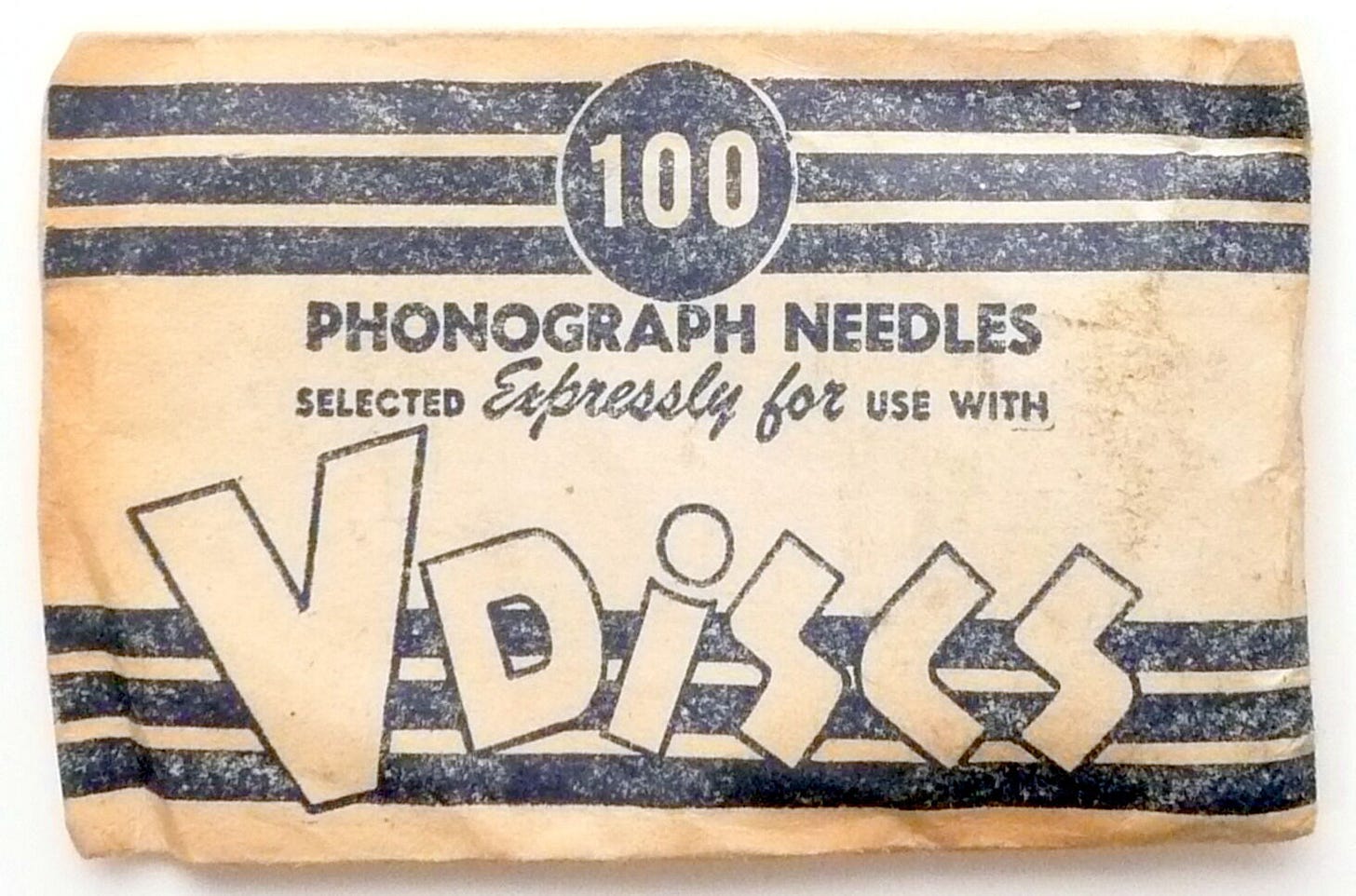

Nostalgic remnants of the 1950s-1980s, vinyl records have a cult following today. It may come as a surprise to many that the first widespread use of vinyl records was the U.S. military’s V-Disc program. Capitalizing on modern vinyl technologies, V-Discs were 12-inch, 78rpm records capable of over six minutes of music per side - a fact that allowed many of the jazz and swing bands to “stretch out” much longer than the standard 10-inch 78rpms popular at the time. V-Discs offered a variety of popular, folk, and classical selections. They were packed in waterproof boxes complete with replacement needles

In addition to the discs and needles, hand-cranked record players were also sent along.

Interestingly, because of the union strike, Petrillo imposed important conditions. He asked that: the V-Discs not be used for any commercial purposes; that the records not be sold; and that all V-Discs and their audio masters and stampers were to be destroyed after the war.

V-Discs were an instant hit overseas and provided huge morale boosts and important entertainment for our troops throughout the war. The V-Disc program ended in 1949, and the Armed Forces set out to honor the agreement they made with Petrillo. The audio masters and stampers were soon destroyed. The leftover V-Discs at bases and on ships were similarly destroyed. On some occasions, the FBI and Provost Marshall’s Office confiscated and destroyed V-Discs that servicemen and women smuggled home. In fact, the story goes that an employee from a Los Angeles record company served time in prison for the illegal possession of over 2500 V-Discs.

For me, all the history and stories just add to the mystique of V-Discs and their important legacy in the history of sound recordings. So now, let’s listen to some more of my favorite V-Discs.

In 1947, Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday appeared together in the movie New Orleans. It was actually Billie Holiday’s only feature film appearance. Armstrong’s band in the film is a powerhouse with among others Kid Ory on trombone, Zutty Singleton on drums, Barney Bigard on clarinet, and Meade Lux Lewis on piano. The film also featured band leader Woody Herman.

I prefer the original 1947 poster from a Swedish movie theater, which rightfully shows the real stars of the movie:

In February of 1947, Louis Armstrong and his Orchestra with Billie Holiday performed a live concert at Carnegie Hall that included a song from their new movie New Orleans, Do You Know What It Means To Miss New Orleans. The performance was recorded on a V-Disc and released in May 1947.

Here is that wonderful recording. I particularly like how Billie Holiday kicks in at the 4:18 minute mark:

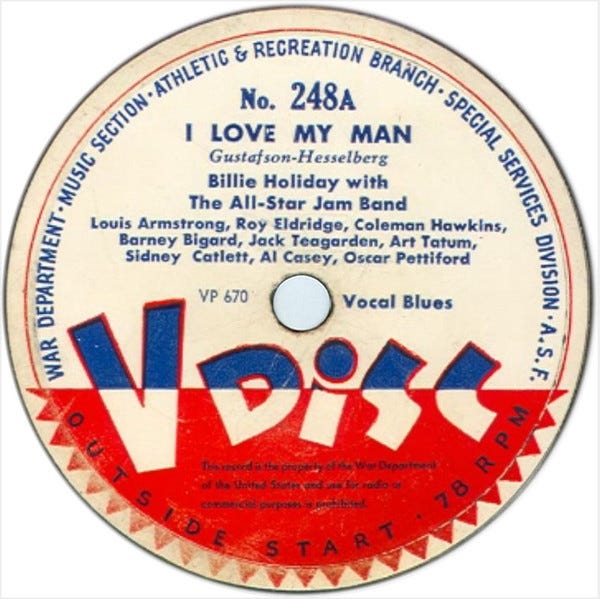

Holiday had made an earlier V-Disc that I also like a lot, I Love My Man. This is one of my favorite Holiday songs, recorded live at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City on January 18, 1944. It was released on V-Disc in June 1944:

Here is that recording with a killer band backing her up:

One of the really great features of the V-Disc program was that it allowed for musicians signed by different recording labels to record together, who might have otherwise been restricted.

Another V-Disc I like is Beaver Junction on side A and Kansas City Stride on the flip side by the Basie band with Lester Young, recorded on May 27, 1944 and released in August 1944:

Here’s one more for the road. Along with Snowfall, Let’s Put Out The Lights is one of my favorite Claude Thornhill tunes. It was recorded in New York City on December 15, 1947 and released in May 1948. Skip ahead to the 3:30 minute mark for the start of the song:

In the end, the V-Disc program confirmed that music - and a lot of it - could make a difference in the war effort. The V-Discs were, as Captain Vincent put it himself, “a slice of America to the boys overseas.”

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles in and explore the waters of underrated pianist and arranger Claude Thornhill.

If you feel so inclined and would like to buy me a cup of coffee to show your guide some appreciation for this and past weeks’ journeys, please hit this link. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button at the bottom of the page. Also, if you feel so inclined, become a subscriber to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button below.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey by Tyler King is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….