I think the cassette played a crucial role as a tool of communication, a tool that was very dear to us. It served to raise awareness and awaken the consciences of those who felt that everything was already lost, or that we didn’t have the wherewithal to win our struggle. It allowed the Tuareg world to develop its own conscience and move forward. In our milieu, the only thing that can make us question ourselves is music. Because we listen to a lot of music, we love music, we love poetry. We don’t read. We’re not a people who read. So, the only reading we have, about ourselves and about the outside world, is music.

- Keltoum Sennhauser

Over the past few months, I have learned about the significant impact cassettes played in spreading music in northern Africa, in particular how they contributed to growing the success of the Tuareg band, Tinariwen.

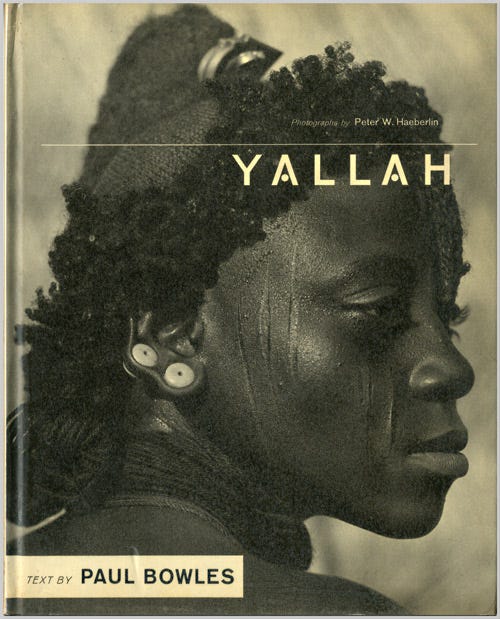

As I wrote in our journey with Clifford Thornton last month, in his 1957 book Yallah,

Paul Bowles wrote, “To lovers of the Sahara, its most fascinating inhabitants are the Touareg. There are obvious reasons for the interest they excite: they have chosen to live in one of the most distant and desolate regions of the world - the very center of the Sahara…. The Touareg were known as the ‘pirates of the desert’, and were hated and feared by everyone who had ever come within reach of their fast racing camels.”

I first read about the Touareg in Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky. Port’s wife Kit was kidnapped by them and held as a slave. Bowles’ description of the Touareg intrigued me. The second time I read about them was in his 1963 book, Their Heads Are Green and Their Hands Are Blue. In the chapter, The Baptism of Solitude, he describes the Touareg in a way that caught my attention again:

It is scarcely fair to refer to these proud people as Touareg. The word is a term of opprobrium meaning “lost souls,” given them by their traditional enemies the Arabs, but one which, in the outside world, has stuck. They call themselves imochagh, the free ones. Among all the Berber-speaking peoples, they are the only ones who have devised a way of writing their language. No one knows how long their alphabet has been in use, but it is a true phonetic alphabet, quite as well planned and logical as the Roman, with twenty-three simple and thirteen compound letters.

You can read the entire Clifford Thornton journey here:

However, it was only recently that I learned about the Tuareg diaspora of the 1970s and 1980s and their struggle for political and cultural renewal following Mali’s independence in 1960. I also learned about their guitar music, described as “the real desert blues, played by Tuareg tribesmen who live in pain every day…a Kalashnikov in one hand and a guitar on their back.”

During this decades-long struggle for renewal, it was the music that kept scattered Tuareg settlements throughout remote desert regions connected and unified.

In Conflict and Conflict Resolution in the Sahel: The Tuareg Insurgency in Mali, written in 1998 for the US Army War College, Army of the Republic of Mali Lieutenant Colonel Kalifa Keita describes the Tuareg this way:

Tuaregs were once renowned as desert raiders, traders, and warriors. Their proclivity for slave raiding, banditry, and smuggling did not endear them to the authorities of other Sahelian societies. Typical, Tuaregs were wide-ranging nomads whose wealth in livestock provided material security in a difficult environment.

The French defeated and subdued Tuareg groups during the consolidation of their West African empire in the late 19th century. However, Tuareg society proved to be highly resilient and resistant to change during the colonial era, largely impervious to enculturation by colonial authorities.

For decades under colonial rule, the Tuareg dreamed of an independent state called Azawad, comprised of Tuareg-populated territory in northern Mali, northern Niger, and southern Algeria. So when Mali’s independence came in the spring of 1960, they expected an independent Tuareg; however, that was not to be the case. Sadly, just two years after Mali’s independence, Tuareg-populated northern regions had been placed under a repressive military administration, resulting in the first Tuareg rebellion in 1962.

By the end of 1964, the government had crushed the rebellion. The government’s counterinsurgency operations had shattered many communities, destroying livestock, and sending thousands of newly impoverished peoples to the refuge of neighboring countries, where they formed an indigent minority.

This itinerant generation of “lost souls” now became known as the Ishumar - “the unemployed”, from the french word chômeur, or unemployed person. In the Tuareg ghettos that sprang up in the Sahara during the 1970s, this generation developed its own cultural and intellectual movement called teshumara - “the way of the unemployed”. This generation of poets and singers fashioned a new, modern Tuareg music based on their traditional drum-based sound with the addition of electric guitars. They circulated their music on homemade cassettes.

This week, we will journey through the Sahara and Tuareg guitar music up until 2003, when it moved into a more studio-produced sound that interests me less.

In 2019, Francis Gooding wrote, “The music of Tinariwen is the root of Tuareg guitar, and that was true long before anyone beyond the Sahara had heard their name. Their music circulated widely (and, in Mali, clandestinely) on cassette, and their poems and songs were known by all other bands, becoming the bedrock of a common repertoire.”

Before the music in the Sahara was shared via cellphones and WhatsApp, the earliest Tinariwen performances were shared on homemade cassettes. Their music at parties, weddings, and open-air jam sessions was recorded on battery-powered boom boxes and transported across the Sahara.

On the liner notes of Tinariwen’s Kel Tinariwen, a 1992 recording released in 2022 by the Wedge label, vocalist Keltoum Sennhauser wrote:

Music was the only form of communication we had that could make people understand what was happening in our own world. There was no radio at the time, no WhatsApp, no social networks, no France 24, nothing! We had to use our own resources. Music had played such an important role during the rebellion. It was like “Lili Marlene” for us! The themes of the songs were just right for the time; they ensured we were all thinking in a synchronized way, with the same mind. The melodies were secondary. For us, it was the words. They were like the air we breathed.

It was out of this grassroots movement in the early 2000s that a loose collective known as Taghreft Tinariwan (Rebuild The Deserts) - later shortened to Tinariwan - appeared out of nowhere playing a strange variant of guitar blues/rock and achieved an international audience.

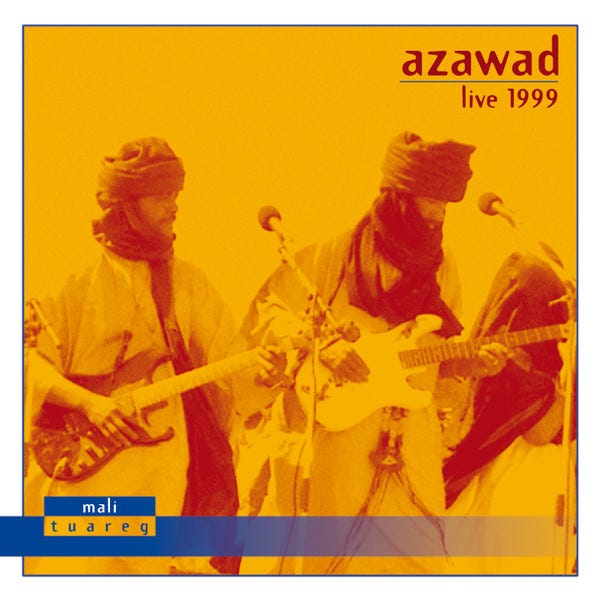

Azawad Live 1999 was Tinariwen’s first-ever gig outside of Africa, recorded at a 1999 live performance at the Nuits Toucouleurs festival in Angers, France.

This album demonstrates the link between the more traditional female Tuareg music, where women take the lead both instrumentally and vocally and men make up the audience and chorus, and the modern, male-dominated guitar sound. For example, contrast this traditional song Tichakatewen Tin Chat Hananin:

…with the more modern song from the same performance Groupe Adagh:

This international debut was set up by Phillippe Brix after he heard Tinariwen play at a 1998 festival in Bamako in Mali. He was managing the French world music collective Lo’Jo, who was sharing the bill with a Tuareg group. He invited them to play in France. They accepted and a seven-person group showed up in Angers. They called themselves Azawad, but in effect it was Tinariwen.

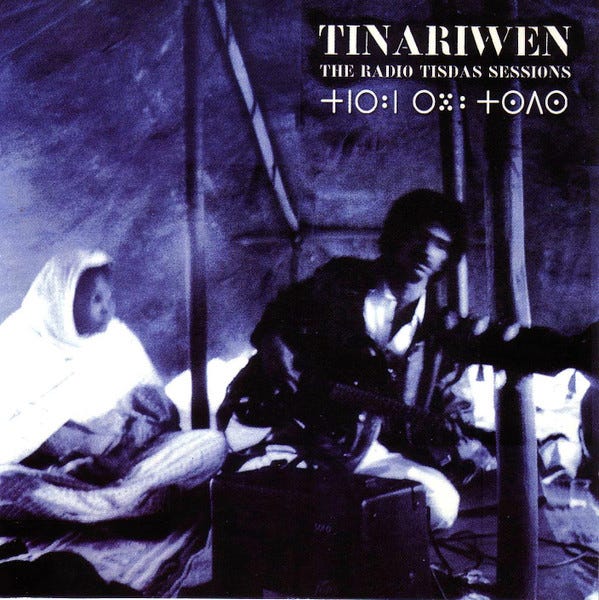

Although Tinariwen had recorded two obscure cassettes beforehand, their 2001 release The Radio Tisdas Sessions is essentially their first record (Azawad Live 1999 was not released until 2009).

Recorded at Radio Tisdas in the northeastern town of Kidal in Mali, The Radio Tisdas Sessions was released by Wayward Records. From the album, here is Imidiwaren:

Outside of an actual live recording, I think this album captures the band in their most natural state.

Here’s another song from The Radio Tisdas Sessions, Afours Afours, which I find has a distinct New Orleans feel:

This is nomadic, itinerate music that in my opinion does not lend itself well to studio-led production. I think these pictures capture that feel:

By the end of the 1980s, Tuareg communities throughout the Sahel had many unemployed and restless young men with considerable military experience. Violence and banditry in northern Mali began to increase, resulting in a second rebellion in 1990. Although a peace accord was signed by the Mali government and Tuareg leaders in January 1991, there would be more rebellions in 2007 and 2010. Unfortunately, the conflict that began in 2012 is still not resolved.

During all this instability, Tinariwen continues to record and perform. However, I still prefer their earlier pre-2003 lo-fi field recordings released before their music became subject to producers in studios for a global audience.

From Chris Kirkley’s excellent “para-ethnographic” Sahel Sounds label, here’s a beautiful and rare example of a female Tuareg guitarist, Amaria Hamadalher playing Bahouche on the essential guitar collection Agrim Agadez:

Tuareg guitar is almost totally dominated by men. This strange gender role reversal in traditional Tuareg music adds a different perspective to male guitarists and singers. Regardless, I think this playing suggests an interesting, perhaps more introspective, sensibility than male guitarists.

Here’s one more for the road. The popularity of Tinariwen led to the recognition of other Mali guitar bands, like Bombino (really like his first recording from 2004) and Alkibar Gignor. Here is Alkibar Gignor’s Dakou, a field recording from Mali in 2011, from his album La Paix released by Sahel Sounds in 2012:

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll stay in Africa for one more week and dig our paddles in to explore the waters of Brian Shimkovitz’s Awesome Tapes in Africa blog and label.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel so inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Well, Dune is a vast Saharan landscape into which I have never ventured. However, when my journey takes me there, I will carry this in my knapsack.

A bit off-topic, but I've always thought the Tuareg were Frank Herbert's model for the Fremen of Dune (but with music).