Things happen in moments, not measures.

-Michael Pisaro, liner notes to Lost Daylight

It’s November. As I look out my window, the sun is setting in the Land of 10,000 Lakes. It’s beginning to feel like winter. It’s also the beginning of the holiday season - our first without our son, who passed away nearly three months ago. My mood brings me to the more meditative music of the early minimalists like Terry Jennings’s Song (1960) and Dennis Johnson’s November (1959), a lugubrious composition and perhaps the first ever minimalist composition. La Monte Young credits it as having inspired his 1964 The Well-Tuned Piano.

Many consider 1964 as year zero for minimalist music, citing Young’s The Well-Tuned Piano and Terry Riley’s In C as the start. But as we can see with the work of Jennings and Johnson, minimalism was happening a good five years earlier.

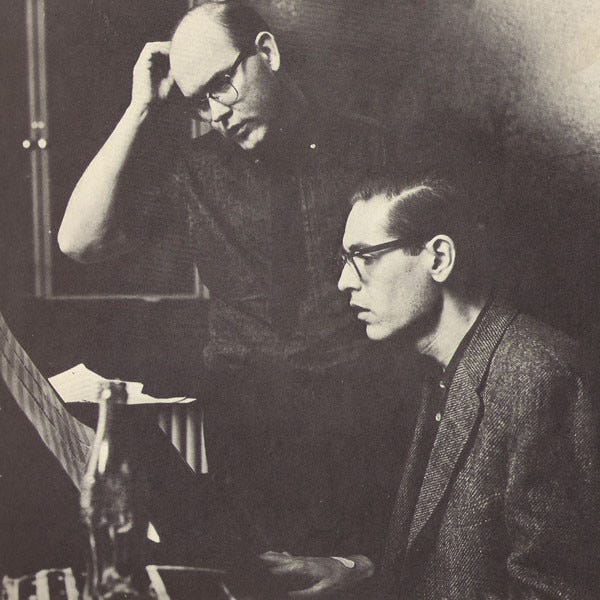

Johnson, along with Young and Jennings, were students at UCLA in the late 1950s exploring the concept of slow, static music. In a 2019 article for Artforum newsletter Young wrote:

I was walking down the hall on the second floor of the music building at UCLA when I heard someone playing the Webern Variations for Piano. I was surprised that anyone in the UCLA music department knew who Webern was, so I opened the door and there was this young man sitting at the piano. He turned out to be Dennis Johnson, a new transfer to UCLA from Caltech.

Young encouraged Johnson to study with Leonard Stein, a disciple of Schoenberg. This was the beginning of a long and creative relationship between the two that resulted in Johnson’s composition November.

For years, November only existed in the form of a 100-minute-long cassette that was noisy, warped, and featured a barking family dog. In 1992, composer and author Kyle Gann constructed a score from the original cassette recording and a partial score that Johnson wrote in the 1980s. Gann's short musical score also requires the performer to improvise for several pages. The outcome was a 2013 4-hour performance by pianist R. Andrew Lee on the Richard Cass Memorial Steinway in White Hall at the University of Missouri in Kansas City. Here is the first of 4 parts of that recording:

What I like about November is how it reflects nature’s slow march toward winter - something a Minnesotan can appreciate. I also love the way you are surprised by unsuspected notes - you feel them more than hear them, like when warm cheeks are caressed by a sudden cold breeze.

Johnson gave up public music performance in 1966 to focus on mathematics, completing a doctorate in the field in 1968. He went on to conduct research projects at NASA and to teach at the University of California, Berkeley. He died on December 20, 2018, in relative obscurity at Pacific Hills Manor Nursing Home in Morgan Hill, California. He had been diagnosed with dementia. Johnson's family shared, "Denny climbed his last mountain today at noon. No ropes. No protection. No more limits."

While still at UCLA, Young introduced Johnson to Terry Jennings, who shared a similar musical vision. Johnson and Jennings became good friends and even rented a loft together in LA. Young recalled, “Dennis, Terry, and I were very sentimental and considered ourselves the three romantics of our time.”

Like Johnson, very little is known about Terry Jennings. For information about Jennings, I relied heavily on Brett Boutwell’s article Terry Jennings, the Lost Minimalist from the Spring 2014 edition of American Music. If minimalism sets out to expose the essence of a subject by eliminating all non-essential forms, then I think the work of Terry Jennings does an outstanding job expressing that.

This week on the Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig in our paddles and explore the world of Terry Jennings.

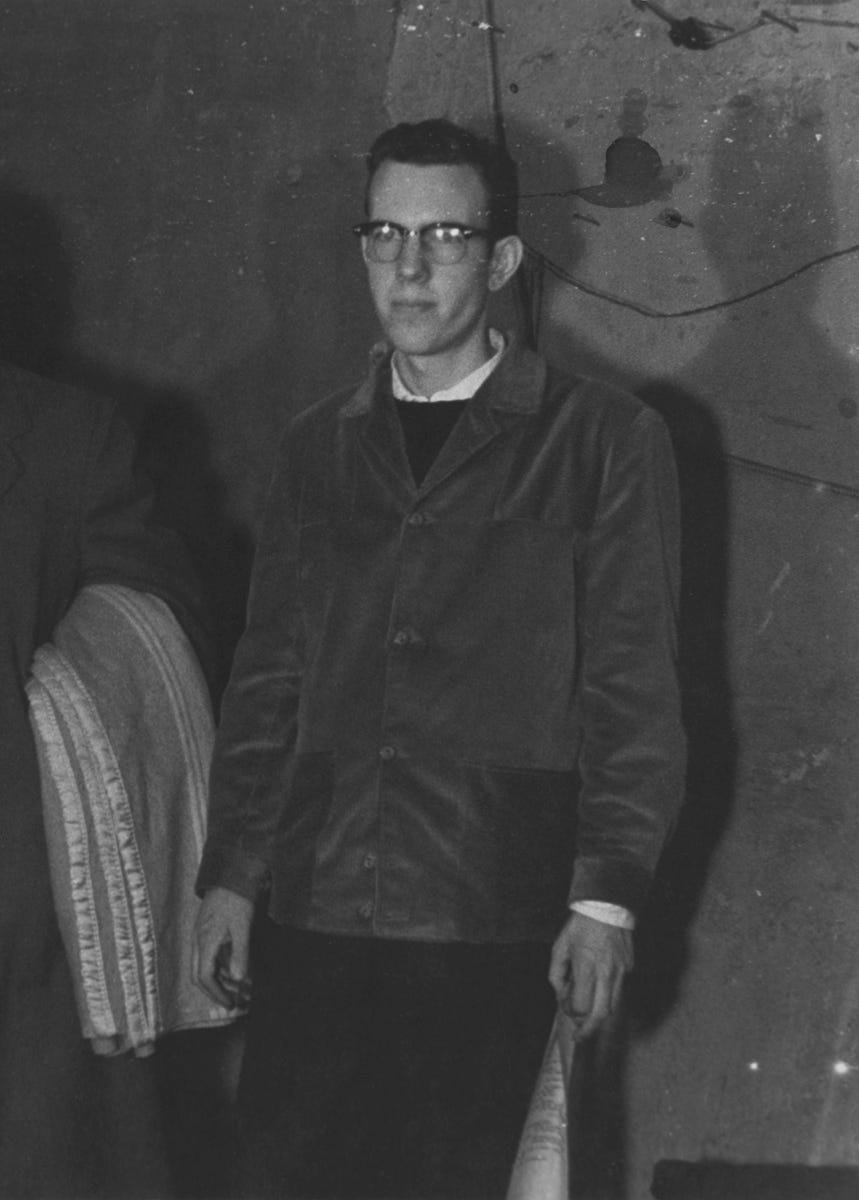

Terry Jennings was born on July 19, 1940, and grew up in the Eagle Rock area in Los Angeles. He was an extraordinarily gifted musically and played clarinet. In junior high school, he arranged Stravinsky for the orchestra, played Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes as a twelve-year-old, and participated in a rehearsal of Schoenberg’s Septet, Op. 29 at the Los Angeles Conservatory. As a teenager, he also played clarinet and saxophone at the nearby jazz and blues clubs. While playing a gig with the Willy Powell Big Blues band in 1953 or 1954 he met La Monte Young, who was also playing in the reed section.

While Jennings was a senior in high school Young was finishing undergraduate work at UCLA, where he adapted serialism to explore sounds of extended duration, like Trio for Strings which he wrote in 1958. In December 1958, loosely using Young’s long-tone composition style, Jennings wrote his first composition Piano Piece. Here is Piano Piece performed by John Tilbury:

When I think about what was going on musically at that time, Piano Piece was radical. In 1958 the classical world was pretty much divided up between resolutely atonal crazy-mathematical 12-toners and chance-obsessed Cageists and the huge, brass-climaxing symphonies of neoclassicists. So what was it that drove Jennings to where he was at?

In the musical world at that time, where music was structured and musicians played things they’d seen others play, I think Jennings was just drawing the music from himself. He wasn’t motivated by imitation. His music was just his own. And with his radical freedom came a certain level of alienation.

According to Boutwell, Jennings’s colleagues recall him as a young man of unusual intelligence and musical talent. For example, according to Terry Riley, he was “a musician of great originality and expressive power.”

However, according to Boutwell:

Yet his contemporaries also remember him as socially withdrawn, passive to a fault, and profoundly aloof - “a man in a dream,” according to his friend Dennis Johnson…

Jennings’s social difficulties may have pushed him toward the affliction that defined his adult life and ultimately led to his demise, narcotics addiction. His experimentation with softer drugs had begun early; it was Jennings (along with the jazz drummer Billy Higgins) who introduced Young to marijuana in the 1950s, when Jennings was a teenager performing alongside jazz and blues musicians in clubs of Los Angeles. By the early 1960s he was abusing heroin.

Clearly, Jennings was heavily influenced by jazz music and the vibrant jazz music scene in Los Angeles in the late 1950s.

When I listen to Jennings’s music I am reminded of Bill Evans, who also suffered from drug addiction. Evans’s suffering can be heard in his music and also seen on his face in the successive Riverside album covers beginning with his Portrait in Jazz in 1960 to Explorations and Live at the Village Vanguard in 1961 to Undercurrent in 1962, with the tell-tale Band-Aid on Evans’s right wrist on the inside cover photo:

When I listen to Evan’s solo Peace Piece recorded in December 1958, I think he plays in a minimalist fashion, but in a jazz sense. Here’s that song:

I’m sure that Jennings was well aware of Evans’s music, and I find it a strange coincidence that Evans’s Peace Piece and Jennings's Piano Piece were both written in 1958 - although I don’t think either musician was aware of the other’s composition.

When Young went to graduate school in Berkeley in 1958, Jennings soon joined him in the San Francisco Bay area. Jennings attended the San Francisco Conservatory and studied composition with Robert Erickson, whose studio at the time included Pauline Oliveros and Terry Riley. Jennings's next compositions: Piano Piece 1960; For Christine Jennings; and Song were all products of this San Francisco environment. Here is Tilbury performing For Christine Jennings:

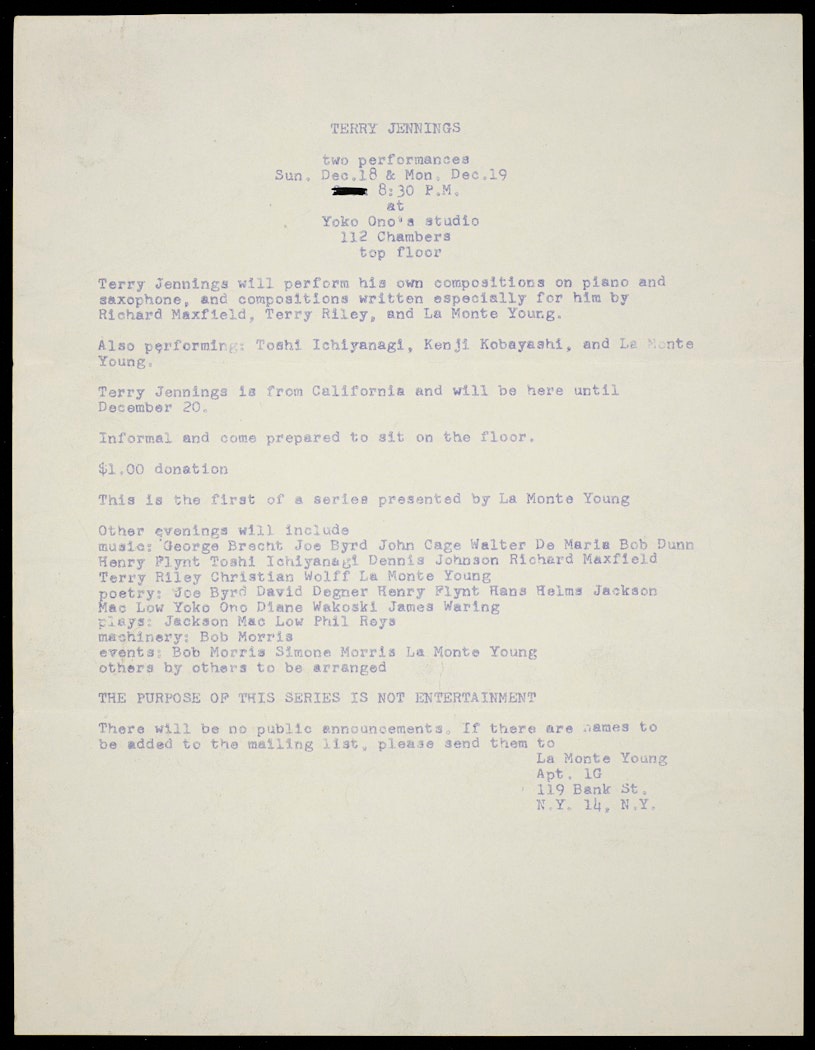

In December of 1960 when Terry Jennings was 20 years old, Young convinced Yoko Ono to invite Jennings to a loft on the top floor of a building she rented at 112 Chambers Street, in downtown Manhattan. Ono intended to use the space as a studio to present new music and ideas, a place unlike any other in the contemporary performance scene dominated by Midtown concert halls. Here’s a 2014 photo of Ono looking up at 112 Chambers Street:

Ono borrowed a baby grand piano from a friend and created makeshift furniture with discarded crates. Over the next six months, Ono and Young presented numerous events by artists, musicians, dancers, and composers that progressed the idea of total nontraditionalism and aggressive experimentation.

The first performance at 112 Chambers Street loft was by Terry Jennings. Here is the event program produced by Young:

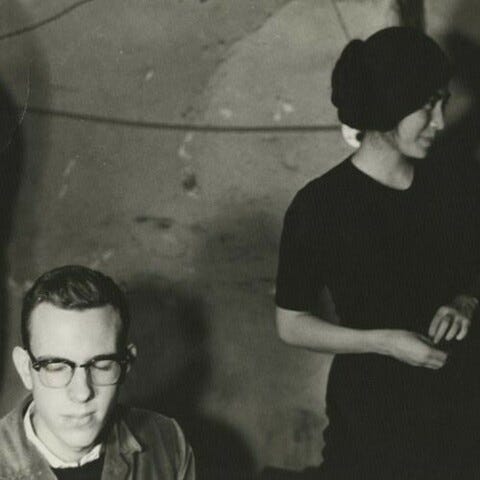

Here is Jennings inside the loft with Ono:

Jennings brought with him from California nine compositions, which as we now know was over half of the 16 compositions (that we know of) that he wrote during his short life. Jennings also brought with him from California a nascent heroin addiction.

Heroin would become a prominent part of Jennings’s social and musical network in New York, a drug culture that included bebop and free-jazz players, avant-garde artists and composers, and experimental rock musicians. I think you can hear the darkness narcotics contributed to Jennings’s work from that time in songs like Piano Piece 1 1965 “Winter Trees.”

Jennings wrote Winter Trees from 1965 to 1966; however, as far as I can tell it was never recorded for release until 2019 on John Tilbury’s Lost Daylight, released by the Another Timbre label:

Here is a nice video of Jennings’s Winter Trees performed by Tilbury filmed at the Volga-Don Canal and Sarepta backwaters in Russia:

In an interview with Boutwell, when Harold Budd was asked about Terry Jennings’s legacy he replied, “Has any American composer done more than Winter Trees?”

It was also during this time Jennings worked alongside many colleagues to fuse elements of New York School experimentation, modal jazz, underground rock, serialism, and non-Western music into improvisational and compositional practices now associated with minimalism and postminimalism. In his book On Minimalism, Kerry O’Brien wrote:

In January 1968, the composer Terry Jennings assembled an “All-Star Band” to perform at Steinway Hall. Earlier in the decade, Jennings had presented sparse, reductive compositions at La Monte Young and Yoko Ono’s loft series, but now he was leading modal, raga-like improvisations, with saxophones and tamburas, that garnered comparisons to the shehnai player Bismillah Khan and the late John Coltrane.

After winning a Leonard Bernstein scholarship in his final year at Goldsmith’s Teacher’s College in London, Welsh musician John Cale attended the Berkshire Music Center in Tanglewood, Massachusetts. Soon he left there and moved to New York to join Young’s Theater Of Eternal Music, a group that included Angus MacLise, Tony Conrad, and Terry Jennings. Young introduced Cale to Jennings and since they were both looking for a place to live, they moved into a loft together on Lispenard Street, just below Canal Street. A few years later, in 1964, Cale co-founded Velvet Underground with Lou Reed.

In May 1967, Jennings played soprano saxophone on the modal jazz exercise Terry’s Cha-Cha with Angus MacLise on hand drum and tambourine, and Cale on electric piano played from a Wollensak recorder. It was released on Cale’s Stainless Gamelan, the third disc in his four-disc anthology New York In The 1960s released in 2001:

Cale recalls that this song is “far too fast for Terry, actually.” In an interview with Hamish Brown in The Wire Cale recalls, “[Jennings] was the slowest man in the universe.” In the same interview, Tony Conrad recalls:

Terry was the slowest person who ever walked the planet. When you called him on the phone there would be a good 45 second pause before he was able to say hello. I mean a serious pause! A pause that went way beyond the conventions of any other human being on earth.

At the time, both Cale and Jennings were heavily involved in New York City's drug scene, and Jennings’s difficulties with drugs eventually landed him in prison. According to Boutwell in an interview with Jeff Perkins, an artist and filmmaker who befriended Jennings in California around 1970:

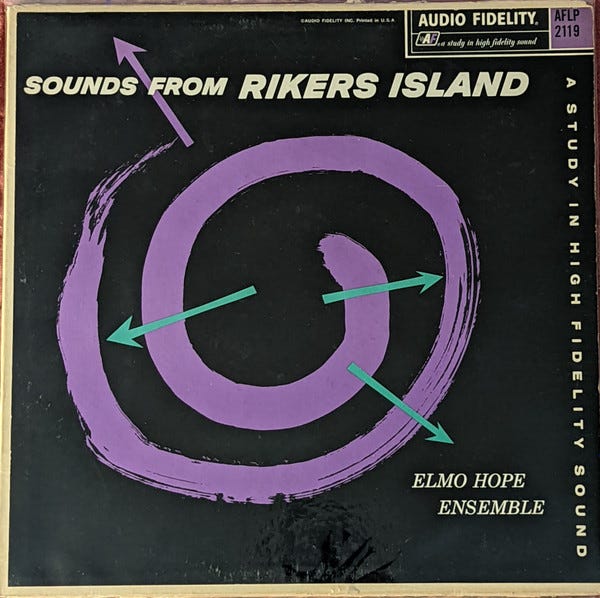

He recalls that Jennings served time alongside fellow addict and noted jazz pianist Elmo Hope, who later praised Jennings’ musicianship. This was likely at Rikers Island, where Hope served time in the early 1960s. Hope later recorded an LP of music with other jazz musicians who passed through the same prison, although Jennings does not appear on the album.

Here’s that album, which incidentally features two Sun Ra musicians the great John Gilmore on tenor saxophone and Ronnie Boykins on bass:

Jennings's jazz influence can also be heard on Short & Sweet, recorded on April 24, 1974, with Charlemagne Palestine for his Sharing A Sonority CD released in 2008:

Soon after his performance at Steinway Hall in New York City, Jennings traveled to England, where his work was championed by Cornelius Cardew English, an experimental music composer, and founder (with Howard Skempton and Michael Parsons) of the Scratch Orchestra, an experimental performing ensemble. When he returned to the United States he settled in LA, where he exerted an influence on the musicians affiliated with the new California Institute of Arts.

According to Boutwell, Jennings last resided in Vallejo, California, and died on December 11, 1981, in nearby Contra Costa County. He is buried beside his mother, father, and sister Christine in Altadena, outside LA.

Here’s one more for the road. In 1992, Jon Gibson released In Good Company and one of the songs Terry’s G Dorian Blues is allegedly composed by Terry Jennings, which would make it his 17th composition since it is not listed as one of the 16 in Boutwell’s 2014 article.

I find Jennings’s work sad and beautiful, with dark undertones that ran through his life.

According to his friend, “Terry struggled with life and that’s the aspect of him I’m left with.” According to Boutwell, “Jennings’s death was undignified and gruesome: in the course of a presumptive drug deal, he was robbed, beaten, and left for dead, his skull crushed.”

Like most human beings, many artists’ work does not contribute to the cultural deposit of humanity. They live out lives of routine and fade away and after a generation or two the earth knows them no more. Some manage to make creative additions that make a mark on culture, however small, that gets passed on through time. Terry Jennings was such an artist. Although his life was cut tragically short, we remember his life and the peace his music brings.

As the days of November get shorter and the nights colder, I look out my window and the sun has set. I wonder what tomorrow brings…

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of the Walter Gross and Jack Lawrence song Tenderly.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel so inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Excellent post.