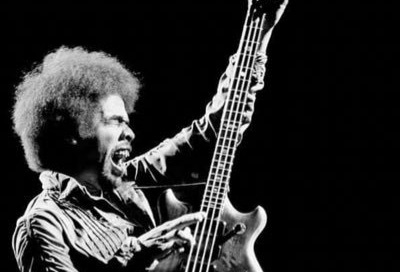

I stumbled onto the music of Stanley Clarke in high school while listening to the local jazz radio station - this was in the late 1970s so there was a mix of jazz fusion and smooth jazz. I’d put it on and do my homework. The DJs played a lot of George Benson, Bob James, Grover Washington Jr., Weather Report, and Spyro Gyra - that sort of thing. Once in a while, a song would make me stop and listen - songs like Stanley Clarke’s School Days, from his album of the same name. That was one of those breakthrough albums early in my jazz journey.

Stanley Clarke recorded School Days in 1976 at Electric Lady Studios in New York City. He had been playing jazz professionally since 1971; however, within two years of releasing School Days, he branched out from jazz focusing more on the pop and R&B worlds. In those seven or so years prior, he amassed an incredible resume as a sideman and leader.

This week on that Big River called Jazz we dig in our paddles to discover the world of Stanley Clarke’s 1972 to 1978 jazz recording period.

Stanley Clarke was born on June 30, 1951, in Philadelphia. He studied piano and double bass at the Settlement Music School in Philadelphia, a large and important school with alumni including Albert Einstein, Michael and Kevin Bacon, Chubby Checker, Joey DeFrancesco, Kevin Eubanks, Christian McBride, and Wallace Roney.

In high school, Clarke met drummer Darryl Brown and played piano in his band the Latin Unit. By 1965, Clarke had switched to bass, and in 1966, when he was 15 years old, he made his professional debut when saxophonist Byard Lancaster invited him to join his band for a week of shows at Philadelphia’s landmark Showboat Lounge, where jazz greats like Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Art Blakey, Stan Getz, and many others had played and recorded.

The Showboat was located in the basement of the Douglass Hotel in Philadelphia:

After her drug conviction in 1947, Billie Holiday came into hard times and often wound up performing at the Showboat. The Douglass was also her home during these engagements. Here’s the historical marker outside where the Douglass Hotel used to be at 1409 Lombard Street:

Clarke was paid $75 for the gig. Incidentally, drummer Darryl Brown also played at the gig. Brown would later play with Grover Washington Jr. and Weather Report before giving up music to become a medical doctor.

In 1971, after graduating from the Philadelphia College of Performing Arts Clarke moved to New York City. He wasted no time and in May 1971 recorded on Joe Henderson’s In Pursuit of Blackness. It was while playing in Henderson’s band that Clarke met Chick Corea, who was sitting in with them for a gig. They formed a bond and after he left Circle in 1971, Corea formed a new group with Clarke called Return to Forever with Joe Farrell on reeds and Brazillians Airto on drums and percussion, and Flora Purim on vocals and percussion. Corea's Return to Forever band relied on both acoustic and electronic instrumentation and played a chamber version of jazz-rock.

Their first album was recorded on February 2–3, 1972:

It was released on Manfred Eicher’s ECM in September 1972 in Germany and Japan but not in the U.S. until 1975. I wrote about Eicher here:

Clarke remained with Return To Forever until 1977.

On November 21, 1972, at the Van Gelder Studio in New Jersey, Clarke recorded on bandmate Joe Farrell’s killer Moon Germs:

Released on CTI Records in 1973, this was Farrell’s third album as a leader. From that album, here is Clarke’s composition Bass Folk Song, with Herbie Hancock on electric piano and Jack DeJohnette on drums:

Eight days after recording Moon Germs, as part of the Stanley Cowell Trio with Cowell on piano and Jimmy Hopps on drums, Clarke recorded Illusion Suite at Sound Ideas Studio in New York City:

From Illusion Suite here is Maimoun:

Clarke recorded his debut as a leader Children of Forever on December 26 and 27, 1972. The album was produced by Corea and released by Polydor in 1973:

In 1974 and 1975 respectively, he recorded Stanley Clarke and Journey to Love, both at Electric Lady Studios in New York City.

Also in 1975, Clarke recorded the classic No Mystery on the Return To Forever album of the same name:

No Mystery won the 1975 Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance, Individual or Group.

In 1976 Clarke recorded School Days, his fourth album as a leader. This is such an epic album that deserves much wider recognition. From that album, here is Quiet Afternoon:

It’s odd to me that the Rolling Stone Album Guide rated School Days with less than two stars. What? This is a stone-cold classic. The album was played constantly on the radio in New York City even into the early 1980s.

In 1978 at Devonshire Studios in North Hollywood, California, Clarke recorded Do You Hear the Voices You Left Behind? on John McLaughlin’s Electric Guitarist album. The song is dedicated to John Coltrane:

I think this song has a decidedly Giant Steps feel:

Although he continued to record in the jazz fusion world, in 1978 Clarke began his move outside jazz and into more pop and R&B worlds. He also began writing scores for film and television.

Here’s one more for the road. An invitation to score an episode for the popular CBS program Pee Wee’s Playhouse in the mid-1980s resulted in an Emmy nomination and opened up a new direction for Clarke producing scores for film and television beginning in 1990 with the American romantic comedy film Book of Love film. In 2019, Clarke composed the soundtrack for Frédéric Tcheng’s film Halston:

From the film here is Carl:

The entire soundtrack is outstanding.

Following his time with Return to Forever, Stanley Clarke embarked on a remarkable solo career that continues today. The list of artists he recorded and toured with over the decades is incredible. In 2022, he won the NEA Jazz Master Award, the highest form of recognition for the jazz field by the U.S. government. Last September he brought his band 4EVER to the 67th Monterey Jazz Festival, where he was honored with the Monterey Jazz Festival Jazz Legends Award. In his own words, “I never really defined myself with any genre of music. I play bass. [pause] I play bass.” Nothing more needs to be said.

Next week, on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles in and explore the world of Artie Shaw.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Nice call, Charles. I love that Clarke and Mtume grove on those. I wrote about Mtume here:

https://sunra.substack.com/p/mtume

You might dig.

His self titled 1974 Stanley Clarke album was his creative peak.One of the better fusion albums. Jazz rock/fusion rapidly went downhill from around 1975,chasing its tail down the rabbit hole before petering out through endless cliches, tiresome noodling and repetitive riffs. Mahavishnu Orchestra, Weather Report, Return To Forever , Larry Coryell's Eleventh House, Gary Boyle's Isotope,Soft Machine...they all flamed out through either radio friendly garbage and/or hopelessly indulgent and embarrassing releases or solo efforts.