That little speck on the left is me heading out of Louisiana, Missouri, on my way downriver. The picture was taken by Steak, a friend and brother who drove in from Kansas City to visit me that morning, Father’s Day. This picture reminds me of the last verse of Bob Dylan’s song Mother of Muses:

Take me to the river, release your charms

Let me lay down a while in your sweet, loving arms

Wake me, shake me, free me from sin

Make me invisible, like the wind

Got a mind that ramble, got a mind that roam

I'm travelin' light and I'm a-slow coming home

I covered 186 miles since last week, from Hannibal, Missouri, to this beach across from St. Genevieve, Missouri:

Tomorrow, I’ll be paddling to Chester, Illinois, Cape Girardeau, Missouri, and on to Cairo - the two weather days put me a little behind schedule. I’ll report on that next week.

On this leg, I stopped at a marina in Louisiana, Missouri. The next morning, Steak and I had breakfast in town at Izola’s at 3rd and Maryland:

This is a classic Rivertown place. It had a framed poster on the wall from 2010, autographed by Bobby Rush and Barbara Carr:

After breakfast, we went up onto the bluff to Henderson Park, named for John Brooks Henderson. He was born in Virginia in 1826 and moved with his family to Henderson County, Missouri, when he was six years old. By the age of ten, he was an orphan. He lived and worked in Louisiana and rose to the rank of General in the Union Army during the Civil War. In 1862, he became a U.S. Senator and in 1864 drafted and introduced the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution outlawing human bondage - the first time the nation’s founding document had been altered in 60 years. The picture of me in the canoe on the river was taken from Henderson Park, looking south.

I later passed through Lock and Dam 25 near Winfield, Missouri. From there, the river cliffs along the eastern shore are beautiful, perhaps none as stunning as the stretch between Grafton, Illinois, where the Illinois River enters the Mississippi River, and Alton, Illinois. Here are the cliffs just south of Grafton:

I also passed the point where the Missouri River dumps into the Mississippi. It’s one thing to stand on the banks and look out at the confluence. It’s another to sit quietly in a canoe and feel the confluence.

My dad’s dad served in WWI as a First Sergeant under General Pershing. After the war, he moved to St. Louis. He lived in a boarding house and met the daughter of the proprietress. They were married, and my dad was born. As a small child, the family moved to Lincoln, Nebraska, on the Platte River, which flows into the Missouri River at Omaha.

When he was eight years old, the family left Lincoln for Grand Junction, Colorado, where my grandfather worked on the great rivers for the Civilian Conservation Corps. My dad “grew up” (his words) in the summers of his early youth in tents along the Colorado River, while his dad built work camps. My dad’s solitary nature was helpful during those early years, as there were no other kids in the camps. Perhaps this is what makes the long, solitary days paddling the river tolerable for me.

My dad always loved America’s great rivers, like the Platte, Yellowstone, and the Missouri, which all feed this confluence. As I pass through it, I honor him.

Where the Missouri River meets the Mississippi River, you can see a distinct line, perhaps the two different colors of the water. When they meet, it is like rivals struggling for supremacy. The current is very chaotic for a long time. Then, before you know it, the river hits the Chain of Rocks and becomes a tempest, like the backside of the dams upriver - unsettling and unpredictable. About an hour downriver from there, the two big rivers have worked out their differences and flow together as one.

A large part of American music came into its own due to the talents and experiences of the musicians at the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. A few miles south starts “The Mound City,” St. Louis - the heart of the continent and the midway point between St. Paul and New Orleans.

When I think about St. Louis, I first think about Jazz, like Scott Joplin and Red McKenzie’s Mound City Blue Blowers, to name just two.

During his time in St. Louis in 1902, Joplin wrote some of his best-known works, including The Entertainer, which gained renewed fame in the 1973 film "The Sting."

The Mound City Blue Blowers performed from 1923 to 1936, with several sessions with jazz stars including Jack Teagarden, Coleman Hawkins, Pee Wee Russell, Muggsy Spanier, Jimmy Dorsey, and Glenn Miller. Here’s McKenzie’s band playing Hello, Lola from a 1929 Bluebird session:

Even in more recent times, St. Louis was home to the Black Artists’ Group (BAG), an important musicians’ collective formed in 1968. BAG was fundamentally a total theater concept, committed to a collaboration of many artistic mediums ranging from theater, music, and dance to visual arts, poetry, and film. It had a tremendously positive and empowering influence on the community.

I wrote about BAG here:

However, the blues played an equally important part in the musical history of St. Louis, not to mention that the city’s hockey team is called The Blues.

In a 2010 Jazztimes article, Nat Hentoff wrote:

I’m too often startled by how much I’ve yet to learn about subjects I’ve covered throughout my life - for example, the blues. Along with writing sections on the blues in my books, I’ve recorded sessions with Otis Spann, Memphis Slim, and Lightnin’ Hopkins. But never before have I learned so much about St. Louis’ powerful and influential role in the blues and American music as in Kevin Belford’s vividly illustrated Devil at the Confluence: The Pre-War Blues Music of St. Louis Missouri.

He goes on to add:

As Belford notes, “I didn’t intend to answer the question, ‘Where were the blues born?’ Instead I wanted to ask the question, ‘What blues were born in St. Louis?’ and show the original blues artists, who they were and what they did so that fans could know what they did and non-fans could be led to discover their music.”

But where the devil did the title come from? Belford cites the story in Pete Weldon’s 1996 essay, “Hellhound on His Trail: Robert Johnson,” in which Son House speculated Johnson had sold his soul to the Devil to become the preeminent bluesman. With that in mind, Belford mythologized the Devil at “the confluence of rivers, roads, rails, and minds [that] met in St. Louis.” And so “The Devil came to the confluence, and made a deal with St. Louis.”

Perhaps one of the Devil’s early deals was in 1914 with W.C. Handy’s The Saint Louis Blues, one of the first blues songs to succeed on a national level:

This song has a storied career, but as a harp guy, perhaps my favorite version is Charlie McCoy’s seldom-heard version from his 1975 album Harpin’ the Blues:

As I move closer to New Orleans, I get a little closer to the heart of the blues.

A little further down the river to Cairo, Illinois, I’ll reach another confluence. This time is the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Cairo was named “Little Egypt” by settlers because they thought the low-lying area, prone to annual flooding, resembled the Nile in Egypt.

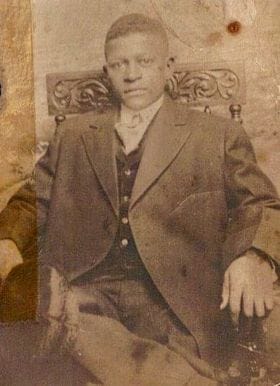

Country blues guitarist Henry Hezekiah Spaulding was born May 7th, 1901, most likely in Future City, Illinois, two miles north of Cairo, before moving to St. Louis to become a barber.

In a 1968 Blues Unlimited interview, at which Big Joe Williams was present, country blues guitarist Henry Townsend recalled:

When I knew Henry Spaulding he was on 19th and Biddle (Streets) and when he died that’s where he was. That’s all I know. No, I don’t know where Henry Spaulding was from really (Big Joe suggested that he was from Future City). Yeah, I think it was Future City, Illinois; I’d heard that, yes. I guess he died somewhere in the 1930s, wasn’t it? Round about 1930, it wasn’t too long after he made his recordings that he died. At the time he made those records he was an older man than I was, so I guess he would have been about 28 or 30 then. (Big Joe concurs).

You can read more about Spaulding in this Blues & Rhythm article by Chris Smith.

Spaulding busked regularly in the Cairo area with Townsend, who appropriated Spaulding’s string-snapping style into his own guitar work.

In the 1970s, Henry Townsend said that:

I was aged about nineteen (born on 27th October 1909) and then I started working around a little bit picking up a few things from Henry Spaulding – he was a barber – he had done a recording for some company, ‘Cairo Blues’, and I fooled around with him for quite some time and of course I stole what I could from him. He and I used to do house parties together. He was an older musician than me – so I followed him around a bit.

Spaulding recorded only two sides in his brief-as-they-come recording career: his signature song Cairo Blues and, on the flipside, Biddle Street Blues (featured above), recorded on May 9, 1929, in Chicago. Brunswick released the record nationally on July 19, 1929, but thinking it would do well locally, gave it a special release in St. Louis on June 10th:

He reportedly died shortly after this recording session.

Here is Spaulding playing Cairo Blues:

In the 1920s, Cairo was a boom town. Next week, I’ll see what it’s like now.

The river south of the last lock and dam is wild. Uninhibited now, it runs freely. However, primarily a commerce river or a barge river, it carries new dangers. The towboats above the Alton push barges three-wide and five deep, with often another single barge next to the towboat, 16 total. At St. Louis, they push barges eight-wide and five deep, 25 total. I saw one with 49 barges, the largest yet. The Port of St. Louis was particularly gnarly as tugboats are active as well. It mellows out some south of there, and the river towns become more scarce and set back from the river.

In some regards, the easy part of the trip may be over…

Your true pilot cares nothing about anything on earth but the river, and his pride in his occupation surpasses the pride of kings.

-Mark Twain

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel so inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Tyler, I grew up in STL (county) & for one year lived on an estate @ the confluence of the MO & Mississippi Rivers. I know just what you mean re: the different streams of water & their colours. Incredibly, I missed your post on the BAG so I'll read it and comment there. Just 1 more thing: STL is the town of trumpet players: Shorty Baker, Clark Terry, Lester Bowie and a certain identity from East St. Louis..

Safe travels!

I enjoy reading about your big journey down the Mississippi and its jazz history. Safe travels!