Ry Cooder

Yeah. If I hadn’t the instrument, I think I surely would’ve ended up in a mental institution...

But if you would tell me who I am, at least take the trouble

to discover what I have been.

-Ralph Ellison

Somewhere between Fred Astaire and Sun Ra is Ry Cooder. I heard his music long before I ever knew I was hearing him.

I was barely a teenager when my oldest brother went off to the Navy, and I dared go into his room. He had a lot of cool stuff in there: a bunch of change on the dresser, a harmonica, some nice Pendleton flannel shirts, and lots of records. I only owned a few records at that time, some 78rpms I bought from a guy on the other side of the lake, and a James Bond album a friend up the street gave me for my birthday.

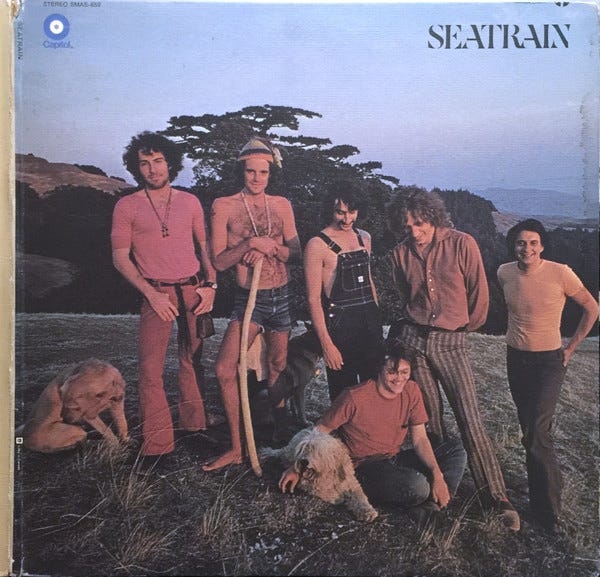

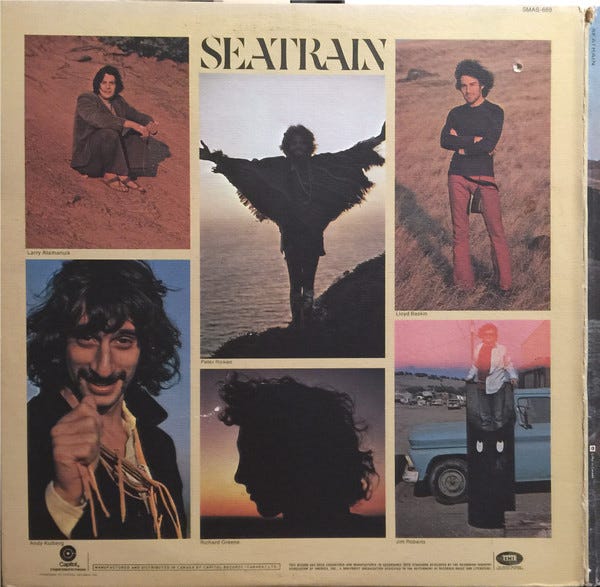

My brother’s records were very interesting and mostly by people and bands with strange names I had never heard of like Leo Kottke, Long John Baldry, John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, Hot Tuna, and Deep Purple. And then there was this one - the first album produced by George Martin after his work with The Beatles.:

It was a gatefold with a nice feel, and I was first attracted to the artistic quality of the album cover. Like those old Folkways albums, it had that grainy, nubbly surface that just felt good in your hands. So I played it. The first song on Side One is I’m Willin’ and it hit me right between the eyes.

As it turned out, Seatrain released this version of Lowell George’s song in 1970, even before Little Feat released it in 1971 as Willin’ on their debut self-titled album (Dutch - I bet you didn’t know that):

A guy named Ry Cooder plays bottleneck guitar on that track.

Beginning in 1967, Cooder was a session man in LA. He recorded on Captain Beefheart’s debut album that year and the following year recorded on both Taj Mahal and Neil Young’s debut albums. In 1969, he played mandolin on a Rolling Stones song I heard a lot on the radio, Love in Vain:

Finally, in 1970, Cooder got the chance to release his first solo album. His journey has been a long and deep walk into the realm of vintage folk, blues, labor songs, and protest music. Through it all, he remains true to his roots.

This week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll explore the roots rock world of Ry Cooder.

In 1982, while in college, I met a woman who traveled the country in a van playing folk music concerts on the college circuit. She was a big fan of David Bromberg and early Steeleye Span. We jammed together a few times, became friends, and stayed in touch. We recorded music we liked on cassettes and sent them back and forth in the mail (the snail-mail equivalent of sharing a playlist). That summer, we met up in Chicago and she gave me this album:

She told me she liked this guy and that the song Big Bad Bill (Is Sweet William Now) reminded her of me (my first name is William - Tyler is my middle name and it’s a long story). When I played it, that was the first time I heard Ry Cooder and knew it was him. To be honest, I didn’t like it much; however, it did put him on my radar.

Ry Cooder was born in West LA in 1947. When he was four, he accidentally stuck a knife in his left eye and was forced to sport a glass one. However, the loss of an eye proved a blessing in disguise. As Cooder told Tony Scherman in a 2008 interview for Stopsmiling magazine:

You talk about fate saying, ‘I think this kid needs to go here, so I’m going to fix it that way.…’ Because a blacklisted friend of my father’s, the same guy who turned me on to Folkways Records, gave me a guitar while I was laid up. I couldn’t do anything. I think he thought the guitar would comfort me, which it did. That it would give me something to do, which it did.

When he got old enough, every week or two he and his friends made the long trip on a bus and then a streetcar, “to this low-rent district way, way downtown, where there was a record store that sold Folkways Records. I bought one per trip.” By his mid-teens, he was thriving on the LA folk and blues scene and was hired as a session man. He was too young for a driver's license and had to be driven to his first record dates.

Cooder’s debut album was released in 1970 by Reprise a subsidiary of Warner Records and followed a roots rock approach that characterized a unique style he’s stayed close to throughout his career. The album features his take on traditional folk and blues songs from Woody Guthrie to Blind Willie Johnson. These were the musicians he grew up listening to and admiring.

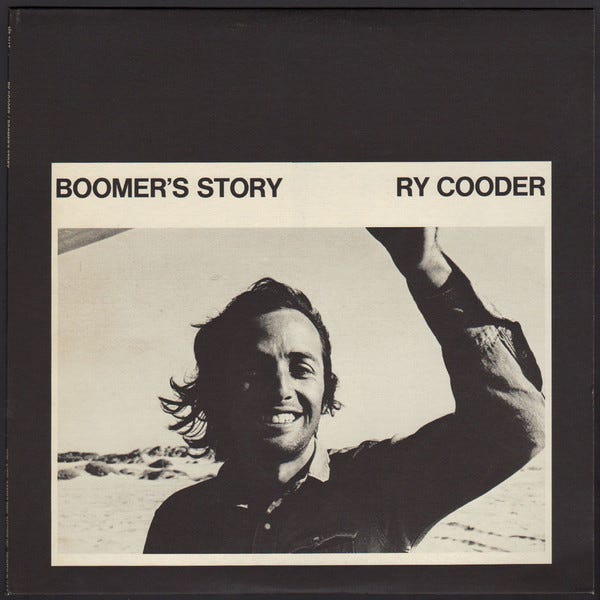

I particularly like his 1972 Boomer’s Story, his third release. Paying homage to Moses Asch, he intended to capture not only the look but the musical feel of those Folkways albums he so coveted:

From that album, I like María Elena, a popular 1932 song written by Mexican composer Lorenzo Barcelata. It was a number-one hit for the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra with Bob Eberly on vocals. Here is Cooder’s version with his unique personal touch.

This song foreshadows Cooder’s fascination with Tex-Mex music.

In 1974, Cooder released Paradise and Lunch, his fourth album. It featured eclectic covers of American gospel and blues singers like George Washington "Wash" Phillips, J.B Lenior, Blind Blake, and this one, Married Man’s a Fool by Blind Willie McTell:

Here’s the original that served as Cooder’s inspiration:

During this time, while living in LA he started to get interested in the Norteño music he heard on the KXLA radio station. Songs like this one from Los Alegres de Terán:

Eager to learn more about this style of music, he contacted the folk historian Chris Strachwitz from Arhoolie Records. You can learn more about Strachwitz here:

In 1975, he accompanied Strachwitz and filmmaker Les Blank on a trip to the Texas border towns to film the movie Chula Fronteras. This is a complex, insightful look at the Chicano experience as mirrored in the lives and music of the most acclaimed Norteño musicians of the Texas-Mexican border, including Los Alegres de Teran, Flaco Jimenez, and Lydia Mendoza.

Inspired to create an instrumental setting for the Norteño tunes he liked, in 1976 he recorded Chicken Skin Music featuring the unlikely interplay of Flaco Jimenez's accordion on songs like Lead Belly’s Goodnight Irene:

This was Cooder’s fifth solo album. His next release was Jazz. As it turned out when my folk music-playing friend dropped Jazz on me in 1982, Cooder was just beginning a new phase in his career - the one I like the most.

After Jazz, Cooder released four more albums until his contract with Warner Records ran out, which kind of reminds me of Til the Money Runs Out, a song on John Hammond’s Wicked Grin:

After releasing ten solo albums, Cooder was deeply disillusioned with the record business. He told Scherman:

And I learned how to tell a story right. I’ve been interested in music as narrative for a while, but I just didn’t know how to do it. You know, the Dust Bowl songs, and all those old blues and medicine-show songs I used to play, that’s all story music. “Alimony’s Killing Me,” that’s a great story. But I went about it wrong. I went about it the way I was told to, as this personality guy. But I figured it out finally. It only took me forty years. Day late, dollar short.

So when an opportunity arose to write a movie soundtrack, he jumped at it. Cooder got his first taste of recording soundtracks on Walter Hill's 1980 Western The Long Riders and the following year he recorded another Hill film Southern Comfort.

When Wim Wenders’ movie Paris, Texas came out in 1984, I saw it down in Lawton, Oklahoma. I loved the film’s soundtrack. When the credits rolled after the film, I noticed it was Ry Cooder and thought, “Hey, that’s the Ry Cooder from Jazz.”

Cooder recalled to Scherman, “What I was trying for in Paris, Texas was simple: the musical equivalent of Harry Dean Stanton's walk, that lonely walk.”

Cooder based the theme song for Paris, Texas on his favorite blues musician Blind Willie Johnson’s song Dark Was the Night - Cold Was the Ground (which he also recorded on his first solo album - featured at the beginning of our journey):

Here’s Blind Willie Johnson playing Dark Was the Night - Cold Was the Ground:

With some momentum from these soundtracks, in 1987 he finally hit the studio again and recorded Get Rhythm, his 11th solo album, and again for Warner Records. The album failed to chart and spent a year sitting on the beach in Santa Monica. “Or longer,” he says. “I did very little for a very long time. It was around ’88. The closing chord. When I said, ‘No more, I’m going.’ Walter Hill helped me out, he made work for me so we had beans in the pot. And [world music producer] Nick Gold threw some interesting things my way. But I just didn’t want to make records anymore. I couldn’t see any point to it, couldn’t see any future in it at all.” He would not make another solo album for almost 20 years.

In 2005, Cooder returned to his roots and recorded Chávez Ravine: A Record by Ry Cooder, a historical album that tells the story of Chávez Ravine, a Mexican-American community demolished in the 1950s to build public housing. The housing was never built. Ultimately the Brooklyn Dodgers built a stadium on the site as part of their move to Los Angeles. Chávez Ravine was the first in his California trilogy, followed by My Name Is Buddy (2007), and concluded with I, Flathead (2008).

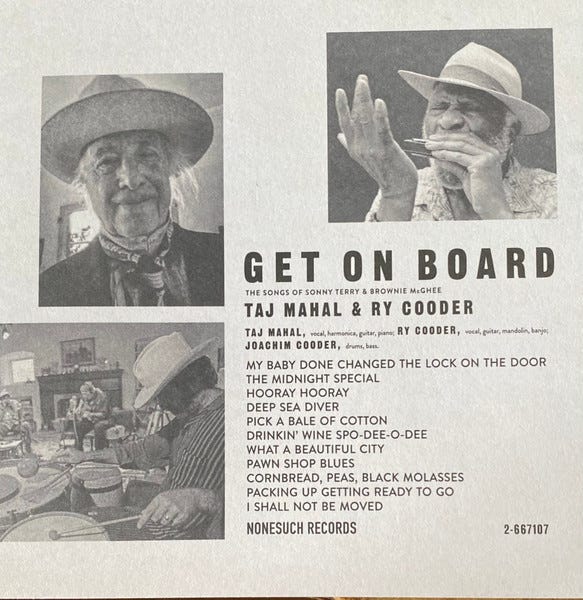

Ry Cooder is still recording. In 2022, Get on Board, his collaboration album with Taj Mahal, won a Grammy. The album was inspired by the 1953 Folkways album of the same title by Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

Here’s Cooder’s album cover:

Always staying close to the roots, Cooder wanted the album cover to be as close as possible to the original Folkways cover. It was a real labor of love.

Here’s one more for the road. In 1999, after all those years in the background, Ry Cooder hit it big with another Wim Wenders documentary film Buena Vista Social Club. The film documents how Cooder brought together an ensemble of legendary Cuban musicians to record an album and film 1998 live performances with the full line-up. The first was in April for two nights in Amsterdam and then in July at Carnegie Hall, New York City.

In the 2008 Stopsmiling interview, Cooder had this to say about life before and after Buena Vista Social Club:

Well, life got better. I didn’t like having a solo career at all. It was the wrong fit. And if you’re doing things you know are wrong for you, then you’re liable to be discouraged and disgruntled.

But I found the answer, and it was while making Buena Vista Social Club. Namely, do something for other people and you’ll do something for yourself. Once that was revealed to me, everything got better. I mean it really did.

That is wise advice.

After years of following Ry Cooder since that day in 1982 when I held Jazz in my hands, I realize that he was one of the few musicians to show deep respect for the texture of the past and combine these elements of ethnic music to make it his own. That’s why I like his music - he is old-school just like me. I just never took the time to put my finger on it.

Next week, on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll leave the midwest and dig our paddles in to explore the world of another roots rocker John Hammond.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

Until then, keep on walking….

My old boss the legendary engineer Lee Herschberg did a lot of work with Ry Cooder.

Never had heard Blind Willie’s “Married Man”, although been enjoying Ry’s version for years; “Paradise and Lunch” is a classic! The California Trilogy deserves a closer examination: each album is a complete concept, yet they’re definitely tied together by extensive liner notes and those allusions to flying saucers.