Many young people in the black American community have neither the knowledge nor the awareness of this heritage. Strata was not just a record label, but a movement based on the idea of self-management and emancipation from industry norms. These artists also… launched community food drives in Detroit.

-Amir Abdullah, aka DJ Amir

As I think about the history of the Free Jazz movement from its beginnings in the 1960s, I see two paths. One that involved the musical journey of the solo instrument. Of course, John Coltrane comes to mind. The other was a more collective approach. For example, among the most popular collectives you have Sun Ra’s Arkestra, the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) in Chicago, the Black Artists’ Group (BAG) in St. Louis, and the Underground Musicians Association (UGMA) in Los Angeles. For some reason, I have always been far more interested in the collective approach. They were more than just music; I admired their deep commitment to the community.

Musically, these collectives worked outside the mainstream pop industry. They nurtured an environment for composing, developing, and performing "creative music" - composed pieces that do not fit neatly into the existing economic and social infrastructures for either jazz or contemporary classical music. They worked outside the mainstream not by choice, but by necessity.

A few weeks ago, I was in Detroit for the first time. Technically, it was the second time - in the 1980s I had a flat traveling through town on my way eventually to New York. I pulled off the highway and found a garage to plug it. Anyway, on this recent occasion, I had dinner right next to Wayne State University and drove by the Detroit Institute of Arts. The visit reminded me of two less popular collectives formed in Detroit after the 1967 riots. This week, on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll look at Detroit’s Strata and Tribe collectives.

The 1967 Detroit riot was the bloodiest of the urban uprisings in the United States during the "Long, hot summer of 1967" when more than 150 race riots erupted across the United States. In Detroit, the riot resulted in 43 deaths, 1,189 injuries, over 7,200 arrests, and more than 400 buildings destroyed.

The first collective to form in the Detroit jazz scene after the riots was the Strata, founded in 1969 by Detroit native Kenny Cox. Then in 1971, Tribe was formed, founded by Phil Ranelin and Wendell Harrison. Both community organizations were built on a creative outlook on urban self-determination and self-actualization.

Before it moved all of its operations to Los Angeles in June 1972, Motown was an important part of the Detroit jazz scene. Jazz music was close to Berry Gordy’s heart - he had run a failed jazz record store in the mid-1950s before founding Motown. So it was not unusual that in 1962 Gordy formed the short-lived Workshop Jazz record label. One of the artists he recorded at the Hitsville USA studio was another Detroit native Roy Brooks. In 1964, the label released his album Beat:

From this album, here is Soulin’:

This album also included the fabulous Blue Mitchell on trumpet. You can read more about him here:

Brooks became an important force in the development of post-riot jazz in Detroit. Another important figure in that development was Yusef Lateef.

Lateef’s music was influenced by the heavy Arab population in the Detroit area. He incorporated many of their instruments into his recordings and was well ahead of the later trend to incorporate Eastern influences in jazz. In 1957, he recorded Jazz For The Thinker, his debut album released on the Savoy label. Right from the opening track, Happyology, you can hear that Arab influence:

Jazz For The Thinker features a full Detroit-based band that had been working a steady gig at the Detroit Klein’s Show Bar. Lateef reminisces about these early quintet recordings:

I worked at Klein’s Show Bar for five years, 6 nights a week. We rehearsed every week so we had so much material that had been rehearsed and exercised. We were so tight we were able to go to New York on off-nights and do two albums, easily…. We got off Sunday night and jumped in the …station wagon, and we would drive all the way to Hackensack, New Jersey, and record on Monday and we’d turn right back to Detroit and open up again on Tuesday.

In the late 1960s, with the rise of Motown, the Motor City music scene was strong. But the 1967 riots changed everything. However, it was on the strength of foundations built by Motown, Brooks, Lateef, and other musicians that jazz was able to find footing in post-riot Detroit. One of those key musicians was Detroit-native pianist Kenny Cox.

In the aftermath of the devastating riots and with the help of John Sinclair, pianist Kenny Cox founded Strata Corporation with its several operating divisions—most notably Strata Productions, Strata Records, Strata Gallery, Strata coffee house, and the non-profit affiliate the Allied Artists Association. Cox was already a leading figure in Detroit’s jazz scene, having recorded two albums for Blue Note: Introducing Kenny Cox and the Contemporary Jazz Quintet; and Multidirection. From the first album, here is Leon Henderson’s composition Diahnn:

On this track, Leon Henderson, the younger brother of Joe Henderson, plays a nice tenor saxophone solo. Trumpet player Charles Moore would go on to record on many excellent Tribe recordings, which we’ll get to in a minute. The Contemporary Jazz Quintet is a solid group and deserves wider recognition - at least outside the Detroit area.

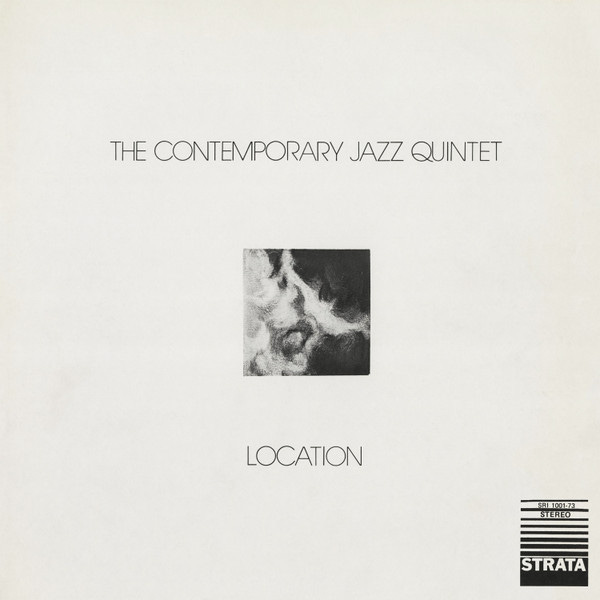

Unfortunately, Strata Records released only a few titles as a record label. Their first release was The Contemporary Jazz Quintet’s Location, recorded in 1972 and released in 1973:

The album compiles a number of their recordings from June 1970 through November 1972. The quintet included stalwarts Cox on piano, Leon Henderson on reeds, Charles Moore on trumpet, Ron Brooks on bass, and Danny Spencer on drums.

During the early 1970s, while Stanley Cowell was working at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor (where he earned a master’s degree), he went to nearby Detroit for some shows at the Strata coffee house. Impressed and inspired by the operation, and particularly the idea of an independent artist-run label, he got together with his friend Charles Tolliver when he returned to NYC and in 1971 organized Strata-East. Originally conceived as an offshoot of the Detroit organization, the label became one of the most successful Black-led, independent labels of its day.

Cowell describes the influence Kenny Cox and the Strata cooperative had on the formation of Strata-East:

I had gone to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and there was a group of Detroit musicians I played with around the Artists Workshop there. Kenny Cox, a pianist, and Charles Moore, a trumpet player, were part of it.

Around 1970 or so, they came to me. They had founded Strata Corporation in Detroit, and they had a concert space, and they were going to produce records. They were all part of this spreading entrepreneurial movement: Musicians should have self-determination in terms of what they put out, not always be beholden to some other people who don’t look like us and probably are ripping us off.

But it moved from a racial-based idea to an entrepreneurial idea. And they wanted us to start a company and affiliate with Strata Corporation. We started the company, but Charles thought we needed a little more autonomy, and so he incorporated it separately as Strata-East Records Incorporated. Connected, but independent.

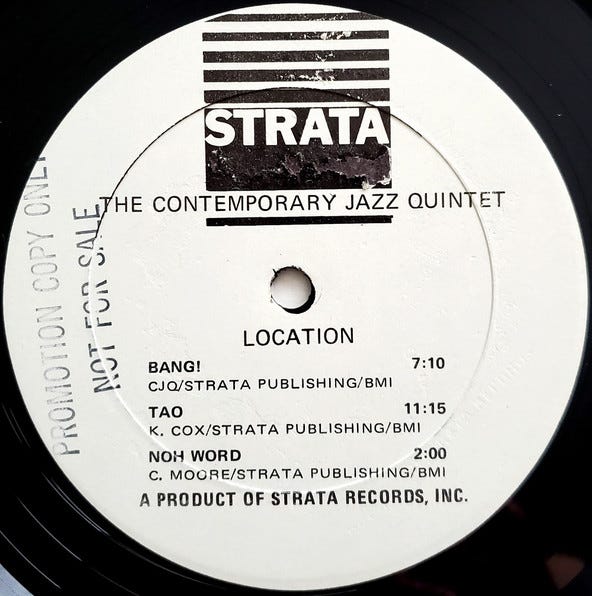

The logo similarities between Strata and Strata-East are not a coincidence, as you can see when you compare the labels.

According to Tolliver:

Kenny and Charles, they had this square logo, with stripes getting smaller down to the end. And I didn’t like that; it looked too much like a flag. I just rounded it into a disc and put “Strata-East” at the bottom, and that became our logo. I trademarked it, and I said, “Okay, now we’re ready to go.”

Here’s the Strata label:

And the Strata-East label:

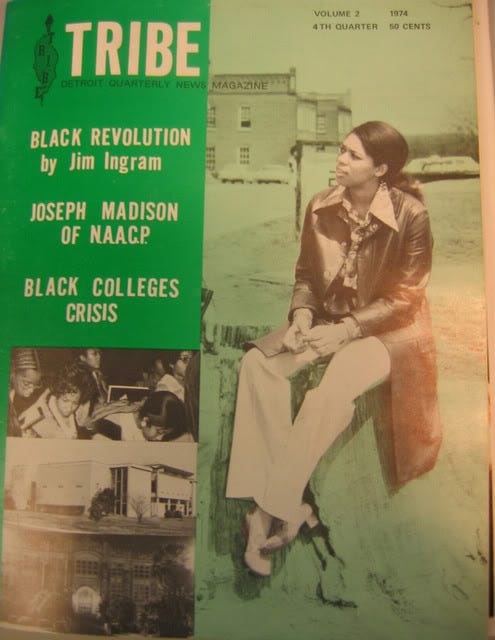

Along with Strata, another important collective was Tribe, founded in 1972 by trombonist Phil Ranelin, saxophonist Wendell Harrison, and Harrison’s first wife, Patricia. Others involved in the enterprise included pianist Harold McKinney and trumpeter Marcus Belgrave. Tribe would grow into a legendary Detroit jazz collective that along with Strata symbolized a growing African-American consciousness within the black community in general and specifically among artists.

Tribe not only sold records, but they also distributed a magazine championing Black self-determination and self-actualization. Here’s the cover of a 1974 issue:

The Tribe record catalog is deep, with many excellent albums. My favorite is Phil Ranelin’s Vibes From The Tribe, recorded at the Strata Studio in September 1975 and released in 1976:

This album is killer and all the songs are righteous. Here’s the title track with Kenny Cox on electric piano:

Side 2 features a very interesting track, He The One We All Knew, Pts. 1 & 2:

This song is essentially the debut of Griot Galaxy, the seminal Detroit band led by Faruq Z. Bey, who on this track is listed as Faruk Hanif Bey. Griot Galaxy settled into its most stable and successful line-up around 1980, when Bey was joined by saxophonists David McMurray and Anthony Holland, as well as bassist Jaribu Shahid and drummer Tani Tabbal. In the 2000s, Bey also contributed to some fine albums with the Northwoods Improvisers. We’ll catch up with the Griot Galaxy a little further down the river….

Here’s one more for the road. Marcus Belgrave’s Gemini II was recorded and released in 1974 and Space Odyssey is perhaps the quintessential Tribe song:

Put the headphones on for this one and check out Roy Brooks playing the mic’d saw. The track also features Wendell Harrison on tenor sax and Harold McKinney on electric piano.

Although these collectives never were able to reach full fruition, I admire the ceaseless efforts of the fearless men and women of Strata and Tribe. They left behind not only a treasure trove of musical and artistic memories of this historic period, but they left us an example of what the collective can accomplish.

Next week, on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles in and explore the world of the Black Artists Group (BAG) from St. Louis.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Thanks, Tyler! Tribe was completely off my radar until now, although Strata and Strata-East were not. I’d also never seen or heard that Savoy Yusef Lateef album! This week’s post is a treasure trove.

Hi Tyler. Your research and text are very good, congratulations. I couldn't find the playlist on Spotify. I typed the title but nothing similar appeared. Can you put the playlist link here. Thanks in advance