Peter Hill Beard

The mingled destinies of wildlife and men...

I came to Africa because I wanted to break free, to set sail… I came for fun, to fulfill my dreams, to learn something new from something old.

I thought of Africa as a place where there was still plenty of room, where you could actually live life rather than have your life run by a world where you wake up in the morning to a traffic jam, rush to catch a bus, struggle to get to the office.

-Peter Beard

Interstate 35 runs 1569 miles through the heart of America, from Duluth, Minnesota, all the way down to a traffic signal at Hidalgo Street in Laredo, Texas, just short of the Mexican border.

It’s a long and lonely highway, and I’ve been lucky enough to travel every mile.

The only place on Interstate 35 where the speed limit is not the standard 65 or 70 mph is a nearly 4-mile stretch in downtown St. Paul. The story goes that it was part of a carefully crafted compromise after a decades-long battle between highway planners and affected St. Paul neighborhoods, better known as RIP 35, who raised concerns about noise, pollution, and increased traffic. However, the inside scoop is that one “affected St. Paul neighbors” was the Catholic Archdiocese of St. Paul, which resided in a massive stone mansion on the bluff overlooking the city. The highway was going to be built right at the bottom of the bluff. The mansion was the previous home of James J. Hill, the railroad baron who in 1889 founded the Great Northern Railway.

In 1925, family members purchased the mansion from the estate and presented it to the Catholic Archdiocese of St. Paul. For the next half-century, the structure served as an office building, school, and residence for the church, and they did not want a highway running through their backyard. So a compromise was struck: the highway speed limit cannot exceed 45 mph. And that was that.

James J. Hill was Peter Hill Beard’s great-grandfather. His great-grandmother, Ruth Hill, was born in St. Paul. His grandmother married Anson McCook Beard II. When he died, she married tobacco heir Pierre Lorilland V, co-founder of Tuxedo Park. After he died, she married Emile Heidsieck, a cousin of Charles Heidsieck, founder of Heidsieck Champagne, who popularized Champagne in the U.S. and was known as “Champagne Charlie.” As the family loved to say, she moved “from cigarettes to champagne.” In a 2023 Wall Street Journal article, Dominic Green wrote that when Beard’s grandmother gave him a camera, “He found a way of life, and an agreeable way to see the world: one-eyed and controlling.”

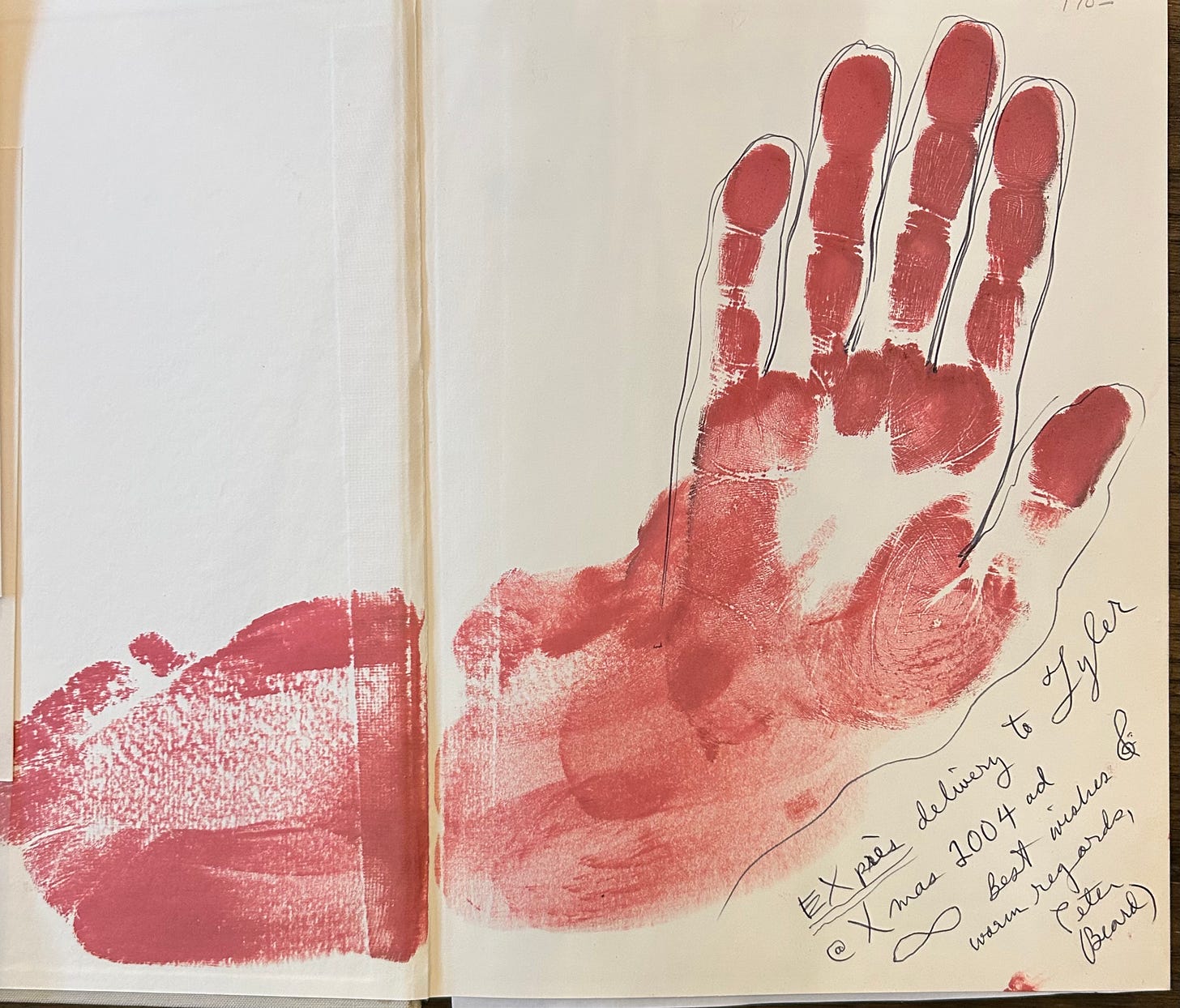

In 2004, I met Peter Beard at the James Ford Bell Museum of Natural History on the University of Minnesota campus. He was in town visiting relatives and friends and gave a talk about wildlife population density and stress in Africa. After the talk, he stuck around to chat with folks and sign his newest book, Zara’s Tales.

He was a charming man. He not only signed Zara’s Tales, but also, by hand and pen, my first edition of his epic, The End of the Game:

This week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles in and explore the world of Peter Hill Beard.

Peter Beard was born in 1938 in New York City. He attended Buckley, a private school in Manhattan, Pomfret, a boarding school in Connecticut, and Yale University, where he majored in art. At Yale, he was tapped into the secret society Scroll and Key.

In 1955, at the age of 17, Beard took his first trip to Africa with Quentin Keynes, the 34-year-old great-grandson of Charles Darwin and the nephew of Maynard Keynes. Quentin Keynes was in the habit of touring schools, showing films to students of his African safaris, and recruiting promising boys as camera bearers. Beard jumped at the opportunity and spent the summer using his Voigtlander camera to photograph wildlife in South Africa, Zululand, Bechuanaland, Portuguese East Africa, Madagascar, and Kenya.

In 1957, the summer after his junior year at Yale, Beard returned to Africa on the Queen Mary with his college friend William K. ‘Bill’ du Pont. On the boat trip over, Beard read Isak Dinesen’s (Karen Blixen) 1937 book Out of Africa. The book captivated him.

On his way to Kenya in December 1961 to arrange a safari for himself and du Pont, Beard arranged a stop in Denmark to travel to Rungstedland and visit Karen Blixen. In June 1962, he met with Blixen again in Rungstedland. On both trips, he took beautiful portraits of Blixen, some of the last before she passed away on September 7, 1962.

Shortly thereafter, he acquired Hog Ranch, 45 acres of wilderness near the Ngong Hills and adjacent to Karen Blixen’s former coffee plantation outside of Nairobi. He was granted special dispensation to own the land by President Jomo Kenyatta as a means to promote the people, flora, and fauna of Kenya in his books, movies, and documentaries.

From 1964 to 1965, Beard worked in Tsavo East National Park in Kenya, photographing and documenting the destruction of an 8,300-square-mile habitat and the subsequent death of over 35,000 elephants and other wildlife, which later became the subject of his first book, The End of the Game, published in 1965 by Viking Press in New York:

In this landmark book, Beard chronicles Africa’s wildlife crisis and implicates a global paradise ever more overpopulated, marching in force downhill toward irreversible problems of density and stress, war, disease, and eventual demise.

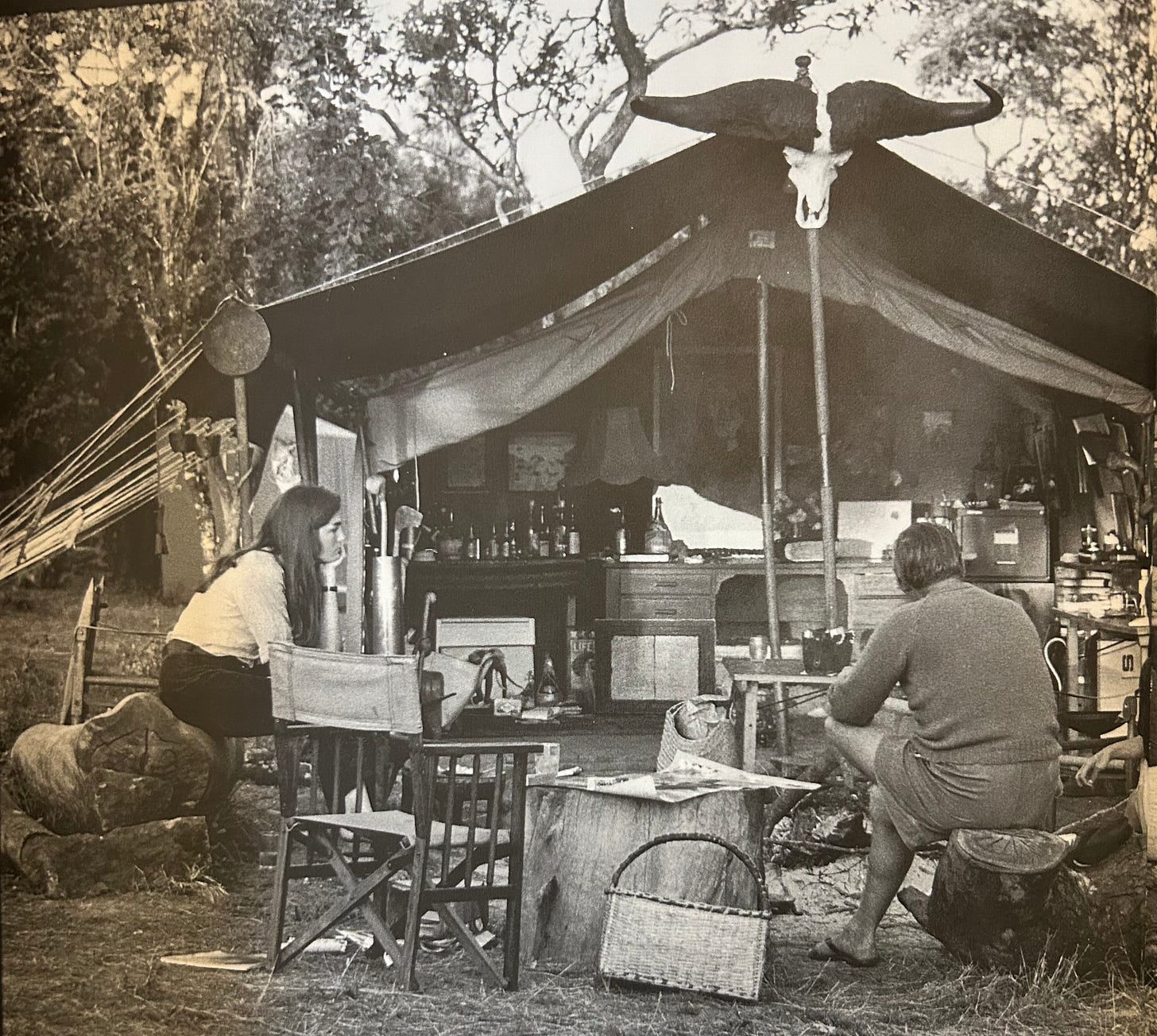

In 1967, he married Mary ‘Minnie’ Cushing, who at the time was working as an assistant to Oscar de la Renta. Beard met Cushing on an African safari. Here they are in 1966 at Beard’s Hog Ranch:

The ceremony took place at Trinity Church, Newport, Rhode Island. The reception was held near Bailey’s Beach at “The Ledges,” the original summer home of the Cushing Family, built in 1867 on one of Newport’s most desirable peninsulas, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. The most famous bandleader in society circles, Peter Duchin and his orchestra, played at their reception.

Peter Duchin was the son of famous American bandleader Eddy Duchin and society beauty Marjorie Oelrichs, of the Newport Oelrichses. The 1974 film The Great Gatsby, with Robert Redford and Mia Farrow, was filmed in her family home, Rosecliff.

Eddy’s father was all charm and good looks. After just two years of professional experience, he auditioned for the piano chair in Leo Reisman’s orchestra. He got the job and, for three years, was featured in Reisman’s band at the Central Park Casino, then New York City’s most popular spot for dancing. In 1931, he took over Reisman’s place as bandleader at the casino. The band played other high-class spots, like the Persian Room at The Plaza in New York City and the Cocoanut Grove in the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles.

Tragically, Peter’s mother died when her only child was five days old. Also, tragically, Peter’s father died of leukemia when he was thirteen. Peter Duchin’s father and mother’s legacy lives on in late-night reruns as portrayed by Tyrone Power and Kim Novak in the 1956 Columbia Pictures film The Eddy Duchin Story.

After the death of both of his parents, Peter was raised by close family friends, New York Governor Averell Harriman and his wife, Marie Norton Harriman. Averell Harriman was the son of railroad baron E. H. Harriman, after whom Harriman State Park is named. The Harriman family donated over 10,000 acres to New York State for the creation of the park, honoring his legacy.

Peter graduated from Yale in 1961, a classmate of Peter Breard. After graduation, like his father, Peter Duchin formed a band to play at La Maisonette, located in the Hotel St. Regis on Fifth Avenue in New York City. For the next three decades, he formed one of the most versatile, prestigious, and sought-after bands of the modern era.

In 1985, Duchin married Brooke Hayward, with whom he had been living since 1981. Her mother was a famous film and stage actress, Margaret Sullavan. Her father was Leland Hayward, the most successful theater and film agent and musical stage producer in the mid-20th century.

Peter Beard’s marriage to Minnie Cushing lasted only a short time. She left him for the producer of the musical Hair. His 1970 divorce from Cushing was the start of a whimsical and theatrical decade typical of Beard’s free-spirited personality.

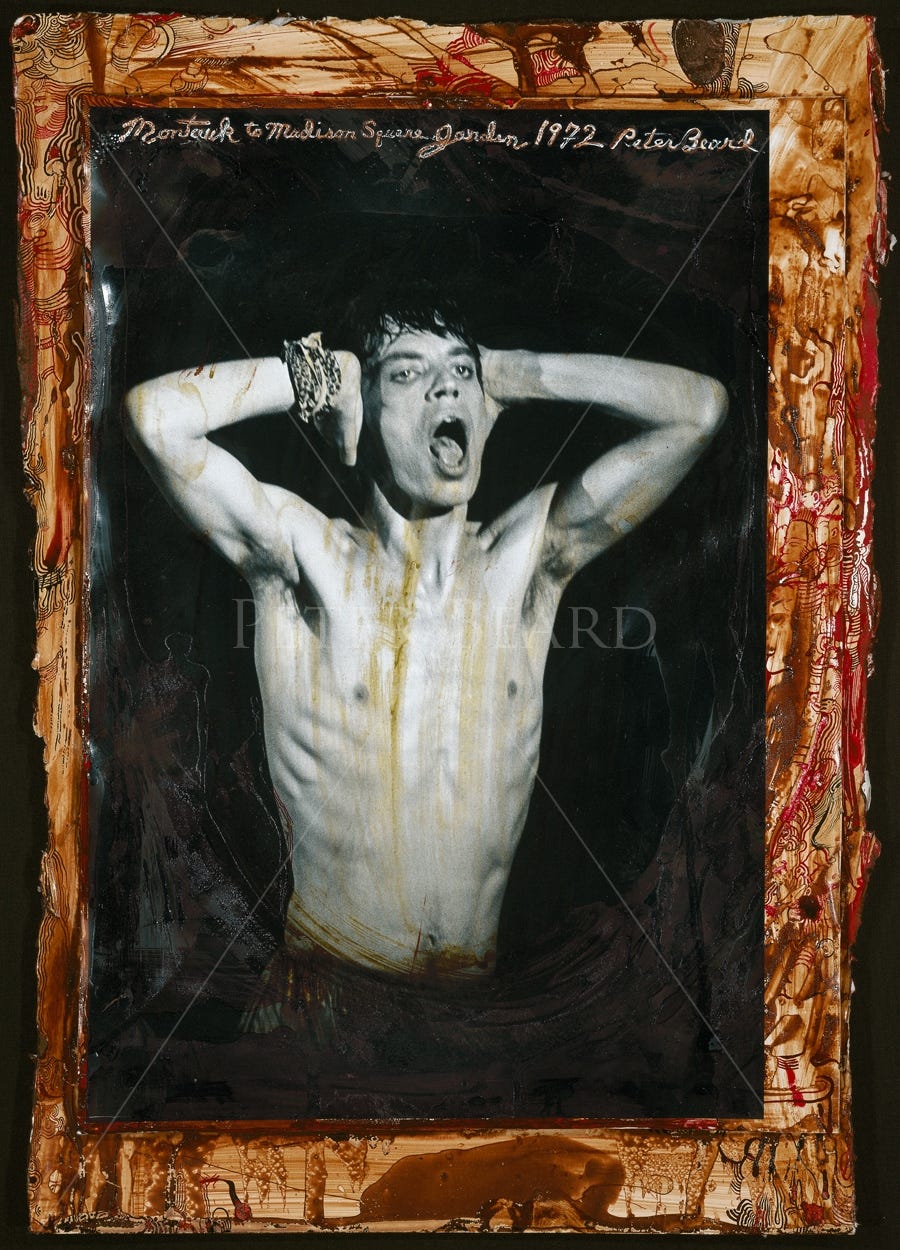

In 1972, photographer Peter Beard was commissioned by Rolling Stone magazine to photograph The Rolling Stones on their “Exile on Main Street” tour. He traveled with the band for two months and became friends with Mick Jagger, as well as with the on-assignment writers Truman Capote and Terry Southern. Beard’s work from this period includes a famous 1972 collage titled: “The Rolling Stones tour pauses at Montauk, 1972”.

From the album, the song Torn And Frayed reminds me of Peter Beard:

He ain’t tied down to no home town

Yeah, and he thought he was reckless

You think he’s bad, he thinks you’re mad

Yeah, and the guitar player gets restless

Mick Jagger wrote, “My dear friend Peter... was a visionary artist and photographer who wasn’t afraid to take risks.” Here’s a picture Beard took from the tour:

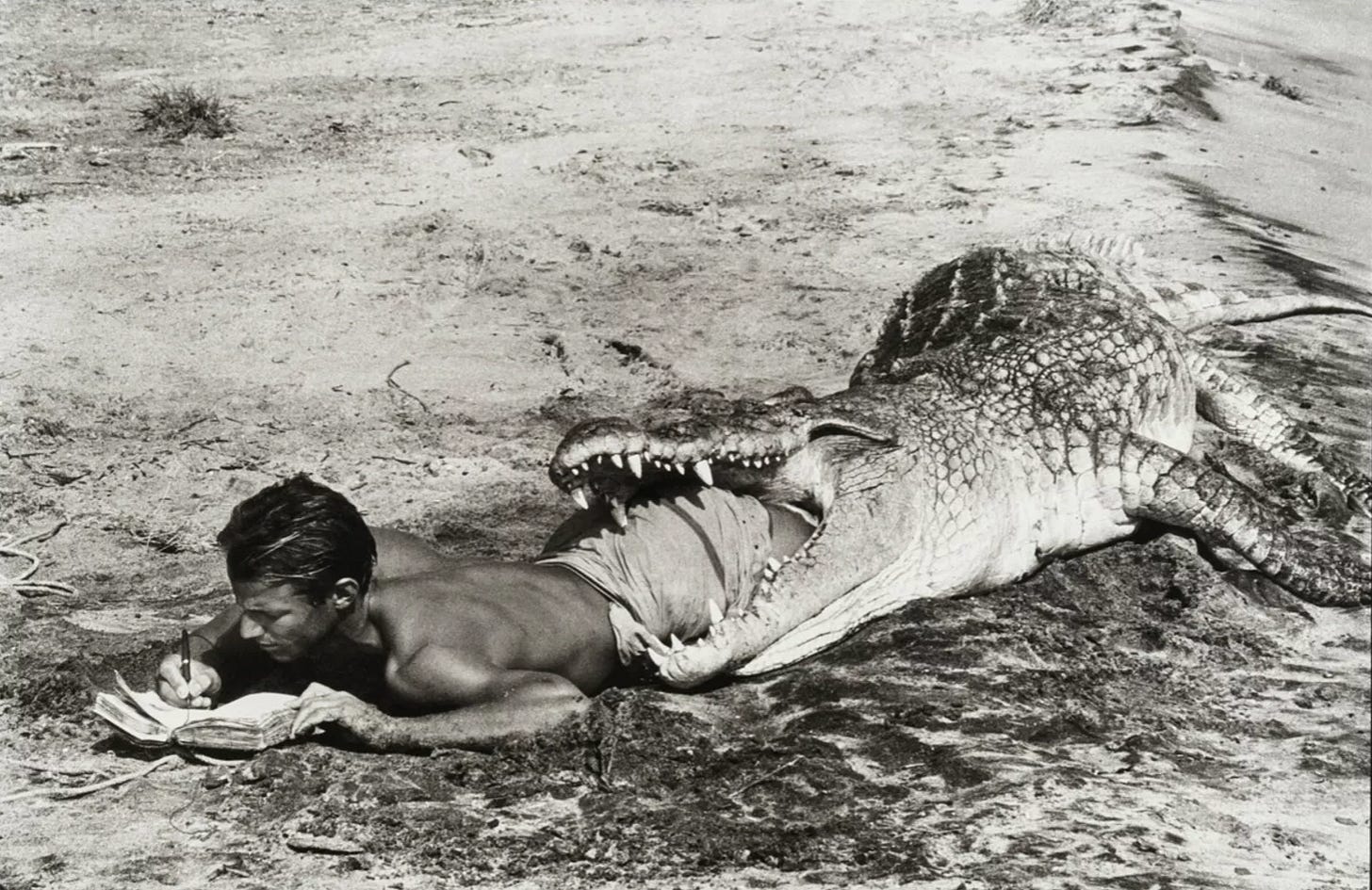

In 1973, the New York Graphic Society in Greenwich, Connecticut, published Beard’s seminal Eyelids of the Morning: The Mingled Destinies of Crocodiles and Men, my favorite Beard book, which chronicles his year-long expedition in 1965 with zoologist Alistair Graham to Kenya’s Lake Rudolf to study the dynamics of giant Nile crocodiles, one of the last great crocodile populations in one of the wildest regions on earth.

In 1977, Fleetwood Mac released Tusk, their infamous follow-up to Rumors.

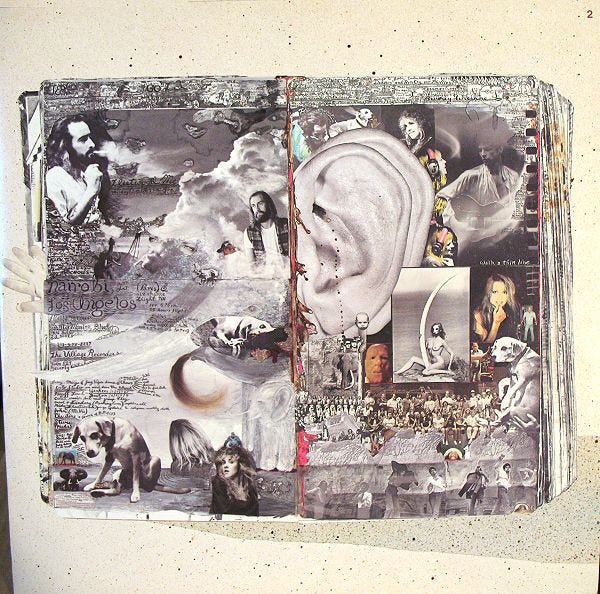

That’s Beard’s photograph on the cover. For a 2020 article in GQ, Dylan Jones wrote:

Beard was in the studio for two weeks, shooting mainly Polaroids of the band and the inner circle. Resembling Peter O’Toole in Lawrence Of Arabia, he was funny and a blast to have around, according to one observer. “Peter seemed unfazed by the amount of drugs that were everywhere in the studio, and I got the feeling that he saw us as just another species of wild creature to capture in his camera’s lens.”

Mick Fleetwood adds:

Peter Beard, one of the three photographers who did some of the pictures on the inside, the artwork, happens to be someone who spent a lot of time in Africa. He came down to the studio and was there for probably about a week, taking pictures of the band. It turned out most of his work was of animals and people’s feet. He then left and during that time got very involved in the conservation of elephants and wildlife. We were just thinking of an album title. We had no idea that his artwork, when it came back probably three, three-and-a-half months later, would have elephant tusks all over it with odd pictures of us stuck in it, so it was just a coincidence. Then it was chosen as a word that we thought sounded good.

Therefore, it’s not surprising the album was called Tusk. Here’s a video from the title track:

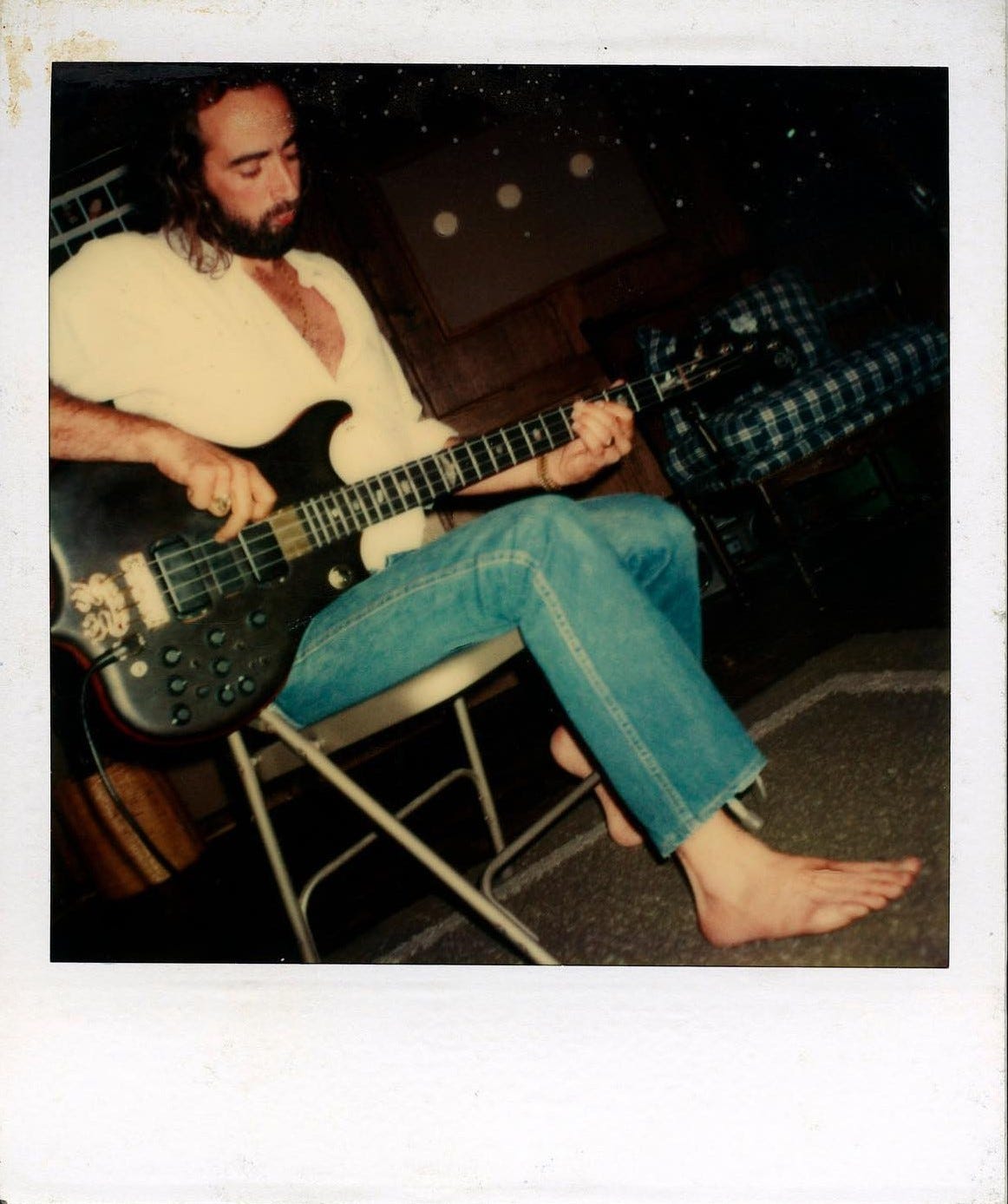

Here are a couple of Beard’s Polaroid shots taken during the recording sessions, which were used to create the collage artwork for the album. Here’s John McVie:

..and Stevie Nicks:

A few of these Polaroid photos were used to create the collage artwork for the album's inner sleeve:

From November 1977 to January 1978, Beard’s first one-man show, called The End of the Game, was held at the International Center of Photography. The exhibition coincided with Doubleday’s reissue of Beard’s The End of the Game, the first since the book’s initial 1965 publication.

The exhibition included his first giant collages and a 60-foot elephant herd print wrapped around the entire building. At the event, Beard was interviewed by R. Couri Hay and had this to say:

I have no belief in life of any kind after death, I can assure you. Remember what Karen Blixen said: “Africa, amongst the continents, will teach it to you: That God and the devil are one.” We’re just sentimentalists who are living in a nursery world of hope. It’s marvelous that death is an end—what’s the matter with that? We have plenty of time to live; we have plenty of time to have fun and really get into things… I have absolutely no fear of dying—it’s one of the most natural processes there is. It just irritates me that due to our greed, lack of consideration, and our stupidity and politics that other creatures have to suffer a fate that we’re all in for prematurely. I just don’t see the point of it, and it irritates me.

You can watch the interview from the show here, which begins shortly after an impromptu interview with Ernst Hemighway’s wife, Mary.

I have to say that I share a different view of death. One which I share more closely with another important conservationist, the late Jane Goodall, who said:

When I die, it is either the end of everything - you are gone, snuffed out, finished, or there is something. I happen to believe there is something - so I can’t think of a more exciting adventure than finding out what the something is.

I do think it’s an important point to ponder, one way or the other.

Today is the second day of the two-day (10/31 - 11/1) sabbat, Samhain. It’s the final stage of the wheel of the year—a pagan calendar marking the sabbats or holidays traditionally celebrated in each season. The wheel reminds us of the beautiful cycle of birth, growth, harvest, and death that occurs not only in nature but also in our lives.

Samhain’s origin is ancient Celtic. It is the final stage of the wheel and represents death. It is also a time when the veil between worlds is at its thinnest, and we can commune with all types of spirits.

Embrace this season, rest, and reflect. Now is the time to ready ourselves, to leave behind that which no longer serves us, and to hold fast to the life-giving people and practices we’ve connected with over the past year.

Here’s one more for the road. In the summer of 1972 during the “Exile on Main Street” tour, while also busy working with Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis the editor for his forthcoming book Longing for Darkness, Beard and Onassis’ younger sister Lee Radziwill began a film project of their aristocratic and deeply eccentric aunt and first cousin, Edith “Big Edie” Ewing Bouvier Beale and her daughter “Little Edie”, who for decades holed up in “Grey Gardens,” their crumbling 14-room 1897 estate home on Lily Pond Lane in East Hampton. The film, completed by Albert and David Maysles, was released in 1975 as Grey Gardens and screened at the 1976 Cannes Film Festival.

However, Beard’s original 16mm 1972 film footage during that visit to Grey Gardens, previously thought to be lost, was found. It features shots of Mick and Bianca Jagger, Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, Truman Capote, and Lee Radziwill all together with the Beales. The film was adapted into the fascinating 2016 documentary That Summer, which premiered at the Telluride Film Festival in the fall of 2017. Here’s the trailer:

In late March 2020, suffering from dementia, Peter Beard left his heart pills on the bedside table and wandered away from his home off Old Montauk Highway east of Deep Hollow Ranch in Montauk.

On April 19, three weeks after his disappearance, his body was found in Camp Hero State Park, a wooded area near his home. He was 82 years old. He died as I suspect he would have hoped, like an old tusker going to the elephant’s graveyard.

Peter Beard’s life was an amazing journey. He didn’t quite fit into any exact hole in the art world. His art, like his life, was unique and wholly his own thing.

In an April 2020 interview, writer Paul Theroux recalled:

He led the way. He was really the first person to chronicle the decline of wildlife—the majestic mega-fauna of East Africa, elephants, lions, cheetahs—and he did it in a characteristic way, by depicting the deaths in iconic images, and writing about his own experiences, using texts from classic books related to Africa.

In a career that spanned six decades and played out across several continents, Peter Beard combined a fascination with nature, a love of travel, and an eye for beauty to create a body of work that resonated across the worlds of fashion, fine art, and both environmental and animal conservation. An amazing work that chronicled the ever precarious mingled destinies of wildlife and man. In the 1988 revised edition of his book The End of the Game, Beard added:

Man and his ways have intruded with little regard for Africa’s customs and privacy. She has been pursued and despoiled. The End of the Game tells part of this story because it deals with the essence of African life, the animal. And with that very license of humanity by which we have presumed to conquer, we are challenged to reflect upon our defeat.

This quote sums up his pessimistic outlook for the fate of not only Africa’s wildlife, but the human race.

Peter Beard had friends in high places. He met them for a coffee, a cigarette, a lunch, a dinner, a party, whatever. He knew everyone, and everyone knew him. But he wasn’t famous. I think that’s the way he liked it - under the radar and free to roam, like the wild animals he loved most. Kwaheri kuonana, Peter. Goodbye and see you soon.

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of Helen Forrest.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….