Peter Green

The end of the game...

Peter Green had the sweetest tone I ever heard and was the only one who gave me the cold sweats.

-B.B. King

This past week, a friend of mine was correct to point out a strong connection between Peter Green and Peter Hill Beard, whom I covered on our last journey.

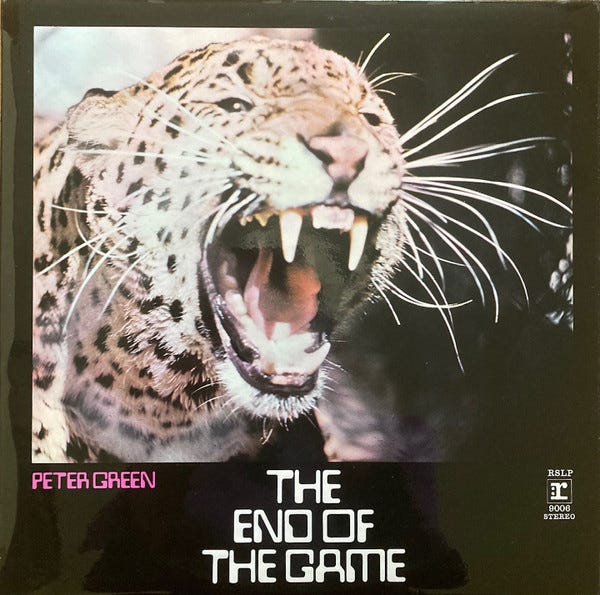

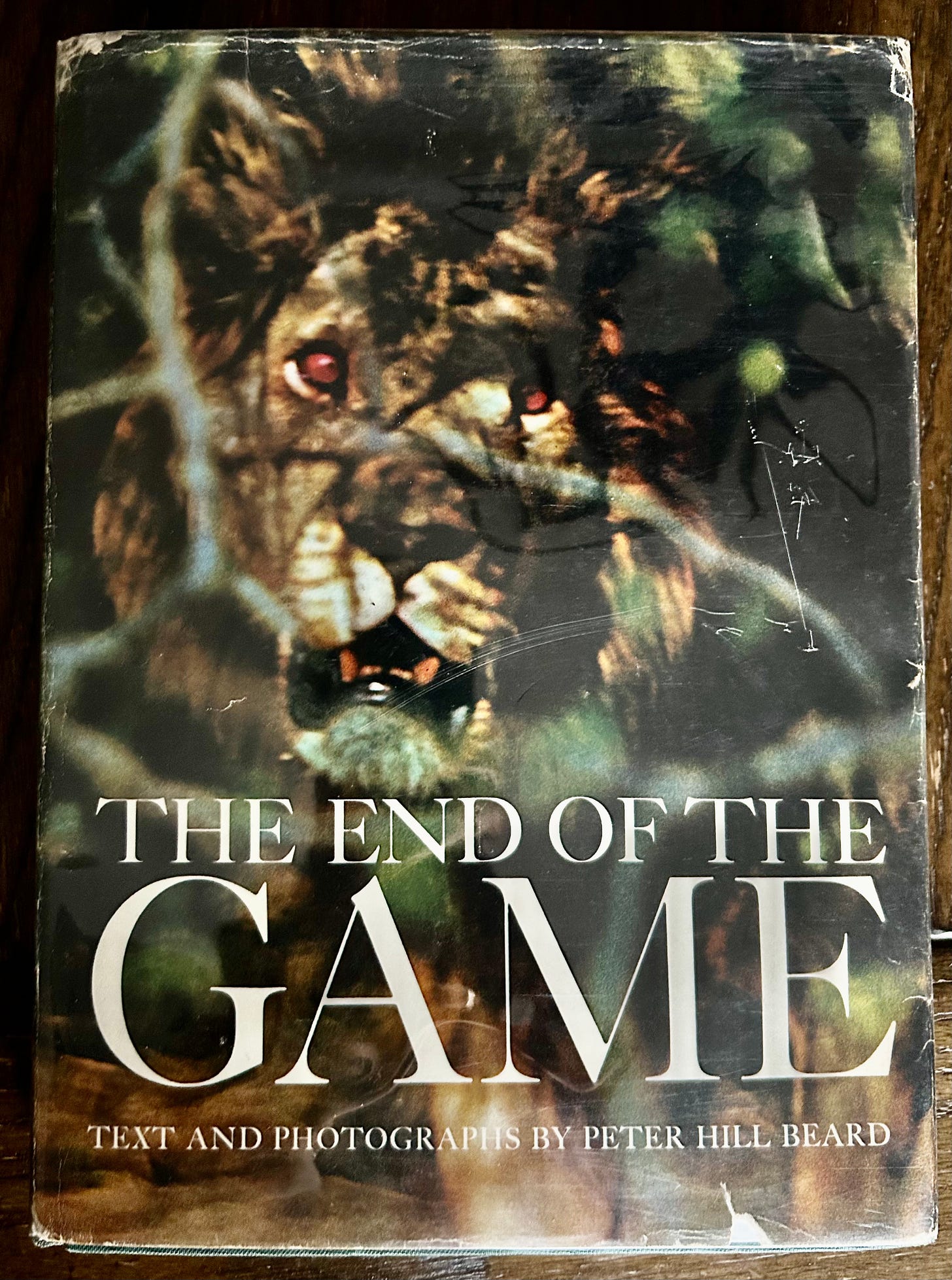

After all, Peter Green’s 1970 album is called The End of the Game and features African wildlife on the front and back covers. I don’t think that’s a coincidence. Even the cover is similar to Peter Beard’s UK edition of The End of the Game, released by Paul Hamlyn in 1965:

So this week’s journey on that Big River called Jazz is at the same time both a kind of epilogue to Peter Hill Beard and a tribute to Peter Green.

In his note to me, my friend made an important point about Peter Green that is worth repeating:

Peter Green’s music moves beyond songs or tunes and into pure energy and expression. It’s immediate transfer of information, as Ellington would say, “beyond category,” or that Sun Ra would call, “the immeasurable equation.”

He shared with me that he was stunned by how Peter Green could convey feelings and emotions through his instrument, not with words or his voice, but with an instrument. Interestingly, that was exactly what I felt the first time I heard Peter Green in the 1980s on John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers' album A Hard Road:

A Hard Road was recorded in 1966 and released in 1967. Among an album of really good blues songs, Peter Green’s unique and searing composition, The Supernatural stuck out to me the most. It wasn’t blues. It was something else. I couldn’t explain it, but I could feel it:

It was a landmark track, as Green played something that could be called controlled feedback, an effect that had never before been used on a recording. It was, in fact, supernatural; however, for some reason, my knowledge of Peter Green really didn’t expand much beyond John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers. I did know that he went on to play with Fleetwood Mac, but beyond Black Magic Woman I couldn’t name a single song he played with them.

My friend went on to tell me Green was his favorite guitarist, and then sent me a list of a few songs he liked most. What follows now is a short summary of that list.

After recording with Mayall on A Hard Road, Green formed a band with bassist John McVie and drummer Mick Fleetwood, which he subsequently named, after them, Fleetwood Mac.

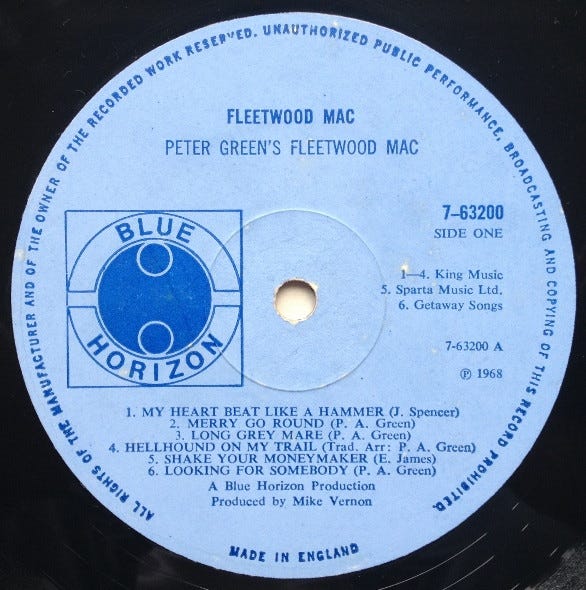

For his birthday, Mayall gave Green some free studio time at Decca Records in West Hampstead, London. Green asked McVie and Fleetwood to join him for the recording session. Produced by Mike Vernon, this was the first recording session of Fleetwood Mac. Their first full-length album was recorded in early 1967, but not released until early 1968 as “Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac.”

However, it was a pair of 1968 singles that brought Green’s writing and playing to the forefront and stand as a reminder of his important and lasting legacy. The first, Albatross, is a simple and beautiful composition:

And the following month, Green’s classic Black Magic Woman was released, which appeared later on Fleetwood Mac’s compilation album, English Rose, released in December 1968:

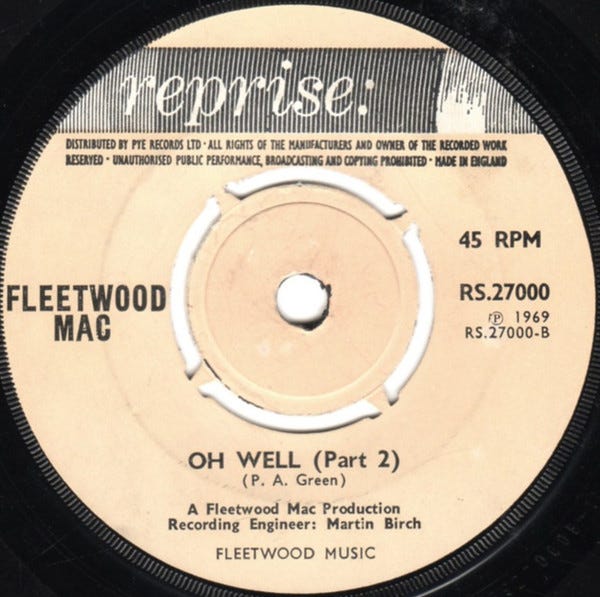

In 1969, Fleetwood Mac released a stunning instrumental, Peter Green’s composition Oh Well (Part 2), recorded on August 3, 1969, at De Lane Lea Studios in London:

Again, this track sticks out. It is something different, in a good way. I have always thought this had an Italian soundtrack feel, something Ennio Morricone might put out. I wrote about Morricone here:

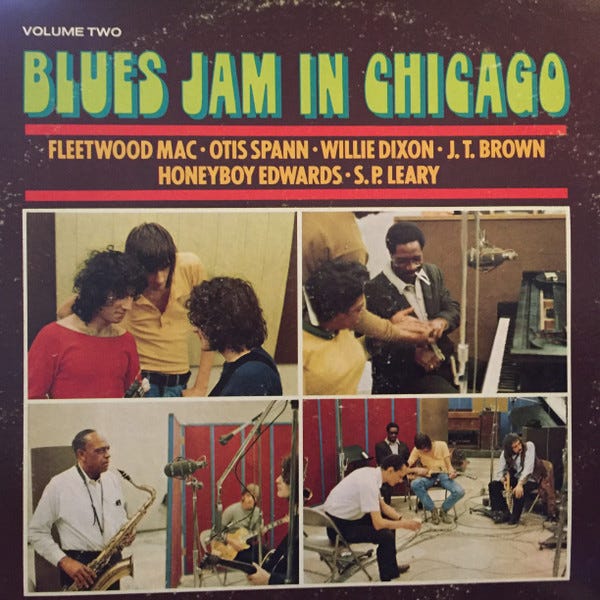

In 1969, Fleetwood Mac traveled to Chicago to cut Blues Jam in Chicago, an album with Chicago’s top bluesmen. It was recorded in January at Chess Records’ Ter Mar Recording Studios, founded in Chicago during the 1950s by Phil and Leonard Chess and named after their sons Terry and Marshall Chess. The album was released in 1970:

From that album, here is Green playing guitar and singing Dave Clark and Al Perkins’ Homework:

Incidentally, the first time I heard the song Homework I was in high school. It was on this smokin’ live version from J. Geils Band’s Live Full House. I just dig Magic Dick’s harmonica playing:

I can’t remember how this album came into my life. I think it was given to me by a guy a year older than me who was also learning to play the harmonica. We had a type of rivalry to see who could play the best, the top harp player in White Bear Lake. He told me about Magic Dick and said listen to Whammer Jammer:

I wore this track out on my turntable.

To get back on the main channel, in early 1970, Green covered B.B. King’s song I’ve Got a Good Mind to Give Up Living at a Fleetwood Mac live show at The Warehouse in New Orleans, LA:

Shortly after this performance, in early 1970, feeling isolated and searching for further musical and spiritual connections, Green left Fleetwood Mac.

From May through June 1970, Green worked on his first solo album, The End of the Game, which was released in December 1970. This album is an improvisational rock masterpiece, very experimental for the time. The band basically played for three days and picked out the highlights, similar to the way Miles Davis edited jam sessions for Bitches Brew. Interestingly, the bass player on The End of the Game was Alex Dmochowski from the underrated The Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation, a band worth a more in-depth look.

Here’s another classic from The End of the Game, Timeless Time:

At some point after he left Fleetwood Mac and released The End of the Game, Peter Green stepped away from music.

In 1978, with the help of his brother Michael, Green began to re-emerge professionally and released another classic single, The Apostle:

On the B-side was Tribal Dance. I like Green’s version of Tribal Dance from his later 1999 Peter Green Splinter Group album Destiny Road:

On this version, you can hear the influence Carlos Santana had on Green.

The Apostle and Tribal Dance single was released in June 1978, before the issue of In The Skies, Green’s first album after The End of the Game. Once the album came out, the single issue was quickly withdrawn from sale. Both songs were subsequently re-recorded for the album’s release. This time, The Apostle was recorded on an electric guitar:

Also in 1978, Green made an uncredited appearance on the song Brown Eyes.on Fleetwood Mac’s double album Tusk, the album on which Peter Beard's photographs appear. This finally brings us full circle back to last week’s Peter Hill Beard journey.

Here’s one more for the road. Peter Green purchased his 1959 Gibson Les Paul Standard guitar, nicknamed “Greeny,” at a secondhand store. Unbeknownst to him at the time, the guitar’s neck pickup had been altered, reversing its polarity and creating a unique “out-of-phase” tone when combined with the bridge pickup, which gave it that signature haunting sound. In 1971 or 1972, Green sold it to Irish rocker Gary Moore, who for decades made the ‘59 Burst his main instrument. He used it extensively in both his work with Thin Lizzy and his solo career.

In 1995, Moore released a tribute album called Blues for Greeny. From that album, here’s Moore playing “Greeny” on Green’s signature track, The Supernatural:

This is a fine cover, and it’s amazing how similar it is to Green’s original recording. Moore played the iconic guitar for almost 30 years before selling it in 2006 to Metallica guitarist Kirk Hammett:

Most would agree that Peter Green’s soulful, melancholic sound cemented his place as one of the British blues movement’s seminal artists; however, I think he was much more than that. Perhaps misunderstood, he was one of the most creative and innovative guitarists who ever lived.

And how many times

Must I be the fool

Before I can make it

Oh make it on home

I’ve got to find a place to sing my words

Is there nobody listening to my song?

Peter Green passed away in his sleep on 25 July 2020. He was 73 years old. Through his music, his legacy lives on.

That Big River called Jazz is deep and wide, and many back channels feed into it, some that are not strictly “jazz.” The last two weeks are a perfect example with Peter Beard and Peter Green’s journeys. But so it goes…

Next week, we get squarely back on that Big River called Jazz, as we dig our paddles into the waters of vocalist Helen Forrest.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

That lion looks like it has been locked in a cage or mental health facility and subjected to psychological warfare for 17 days!

Peter Green accomplished so much in his musical career. Cut too short though due to an unfortunate situation.