Pacific Jazz

Cool and crazy...

This week, our journey starts with a song, but not a Jazz song:

It seems like a long time ago, but all I have to do is play this first song here and I’m back on Carmel Beach….

When we left off, our journey found us in Germany. Now it was time to leave Europe and head back to the USA. From Germany, the Army sent me to Fort Dix in New York to out-process from Active Duty. They told me they’d give me a plane ticket to one of three places: my home of record: White Bear Lake, Minnesota; Norfolk, Virginia; or Oakland, California. I thought for a minute and told them, “I’m going back to California.” I was born in California but grew up in Minnesota. However, my earliest memories are from Sacramento, so there’s a California imprint on my soul. I was 25 years old.

I landed in Oakland, picked up my car and gear, which had been shipped a few weeks earlier, and headed for Carmel. I was still in the Army Reserves at Fort Ord for a few more years, but essentially, for the first time in my life, I was able to come and go as I pleased.

In Carmel, I rented a place just up from the beach and got a part-time job at an antique store on Mission Street. Pretty much every morning, I’d walk down Ocean Avenue by the Harrison Memorial Library to the beach and watch the waves and surfers. I couldn’t surf and never had tried, but I got enough enjoyment from just watching the waves and the surfers, so I never felt the need to learn - a decision I regret now. I might go out and body surf now and again, but I was content on that uncrowded beach “searching for a sunrise and waiting for a cool wind.”

On the weekends, I’d go down to Big Sur and hike or drive around Monterey Bay to Santa Cruz. While in Santa Cruz, I discovered the now-closed Logos Book Store.

Logos was first a used book store, but in the back, they also sold used records - great old jazz records. Every weekend, the owner would put out a small number of collector albums. I’d usually be the first guy there at open on Saturday morning and pick out the cool ones. I bought many of my most prized records there. Like these two:

All you have to do is look at these album covers and you get West Coast Jazz. You’d never see that cover coming out on Blue Note or even on RCA in New York.

The West Coast Sound

West Coast Jazz is frequently characterized as relaxed or often over-arranged; however, I don’t think these characterizations hold up to close scrutiny. I just don’t think the recordings support the view that West Coast musicians were playing an identifiable West Coast or Cool style different from the East Coast or Hard Bop style favored by the New York-based musicians. The music produced out West represented a variety of post-swing approaches to jazz improvisation and arranging that had many parallels to music produced in New York, usually viewed as the center of the jazz world. I find the West Coast sound every bit on par with the East Coast sound. For example, here’s a 1952 cut by Shorty Rogers:

And then here, Harold Land’s 1958 debut album stands up to any of the 4000 series Blue Note albums coming out of New York.

Listen particularly closely to the piano player, Carl Perkins. A real California powerhouse. This was his final recording. He died of a drug overdose 4 months later. He was 29 years old. Those are the Watts Towers in the background of the album cover, which at that time were on the city chopping block.

Also, before Dexter Gordon went east to record with Blue Note, he recorded this 1955 classic for the tiny, black-owned independent Dootone Records in LA (By the way, next week, we’ll take a closer look at the early and important black-owned independent record labels in LA...). Carl Perkins is again on piano:

I think this rivals many of Dexter’s Blue Note recordings – less the distinctive Rudy Van Gelder technical expertise, but still on a high level.

I think musicians and writers on both coasts during the forties and fifties were much more likely to refer to the music as either just Bop or Modern. In the end, the only real distinction for me was not bop or cool, but rather East or West Coast. Here’s another example of the sophistication of the West Coast Sound:

Frank Butler, the drummer, really shines on this, at times I think switching between playing with sticks and his fingertips. Butler was from Kansas City but was associated with the West Coast well before he went east to play with Miles on Seven Steps to Heaven and Coltrane on Kulu Sé Mama.

Furthermore, during the late 1950s, many musicians accepted as outside the California sphere, in particular Oscar Pettiford and the Modern Jazz Quartet, were making music along the same creative and experimental lines as Californians Jimmy Giuffre, Don Cherry, Eric Dolphy, and Chico Hamilton. For example, listen to Eric Dolphy’s playing on this 1959 Chico Hamilton cut:

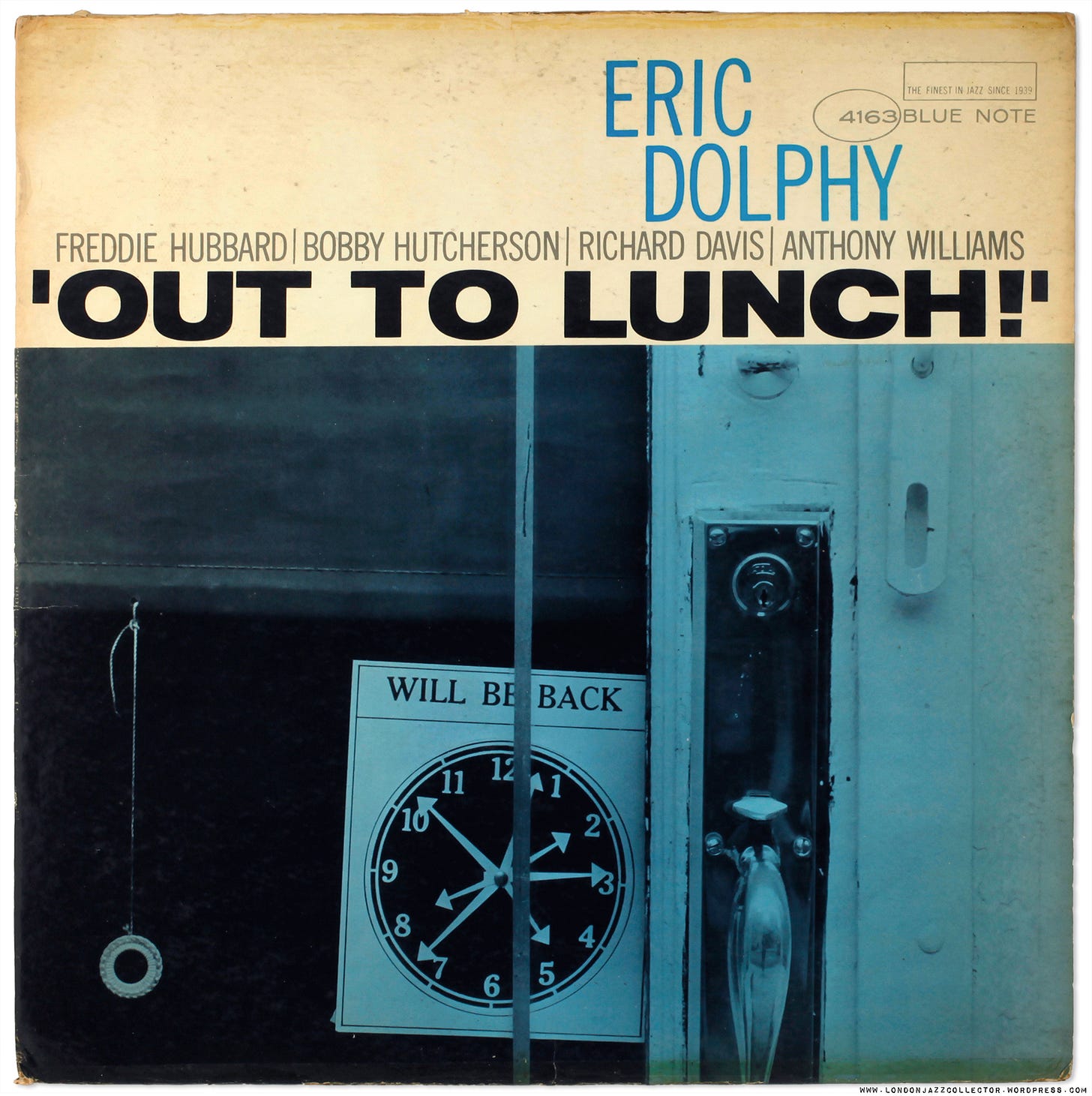

Again, I think this rivals any early modern jazz music coming out of the East Coast in the late 1950s. In fact, it would be home-grown Californian Eric Dolphy who would go east and record Out To Lunch in 1964:

Out to Lunch was Dolphy’s only Blue Note album as a leader and marks the high point of the 1960s Avant-garde jazz scene.

Before Ornette Coleman went east to establish his coterie of Avant-gardists and jazz became dominated by John Coltrane’s increasingly abstract experiment, West Coast Jazz was very popular with critics and both casual and serious jazz fans. However, by the 1960s, jazz was moving east….

My intent here is to show how characterizations that West Coast Jazz was some kind of separate and distinct style are inaccurate. The West Coast musicians were playing modern jazz at the very highest levels. The East Coast jazz was typically shown in low-lit clubs with shadows and cigarette smoke and West Coast jazz was sunny and beachy, but the music was pretty much the same.

But what were the origins of West Coast Jazz….

In the early 1950s, Jazz was moving west. Gerry Mulligan moved out there in 1951. Max Roach moved in 1953 and formed his great quintet with Clifford Brown. Dave Brubeck was on the cover of Time magazine in 1954. Stan Kenton’s progressive band was the hot big band in the country. And at the same time, musicians could pop over to Hollywood and cut movie soundtracks. It was Cool and Crazy!

The West Coast Sound is perhaps best defined by these four Jazz giants - two musicians and two record producers:

Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse All-Stars

Dave Brubeck Quartet

Lester Konig’s Contemporary Records

Richard Bock’s Pacific Jazz Records

Let’s take a quick look at these giants.

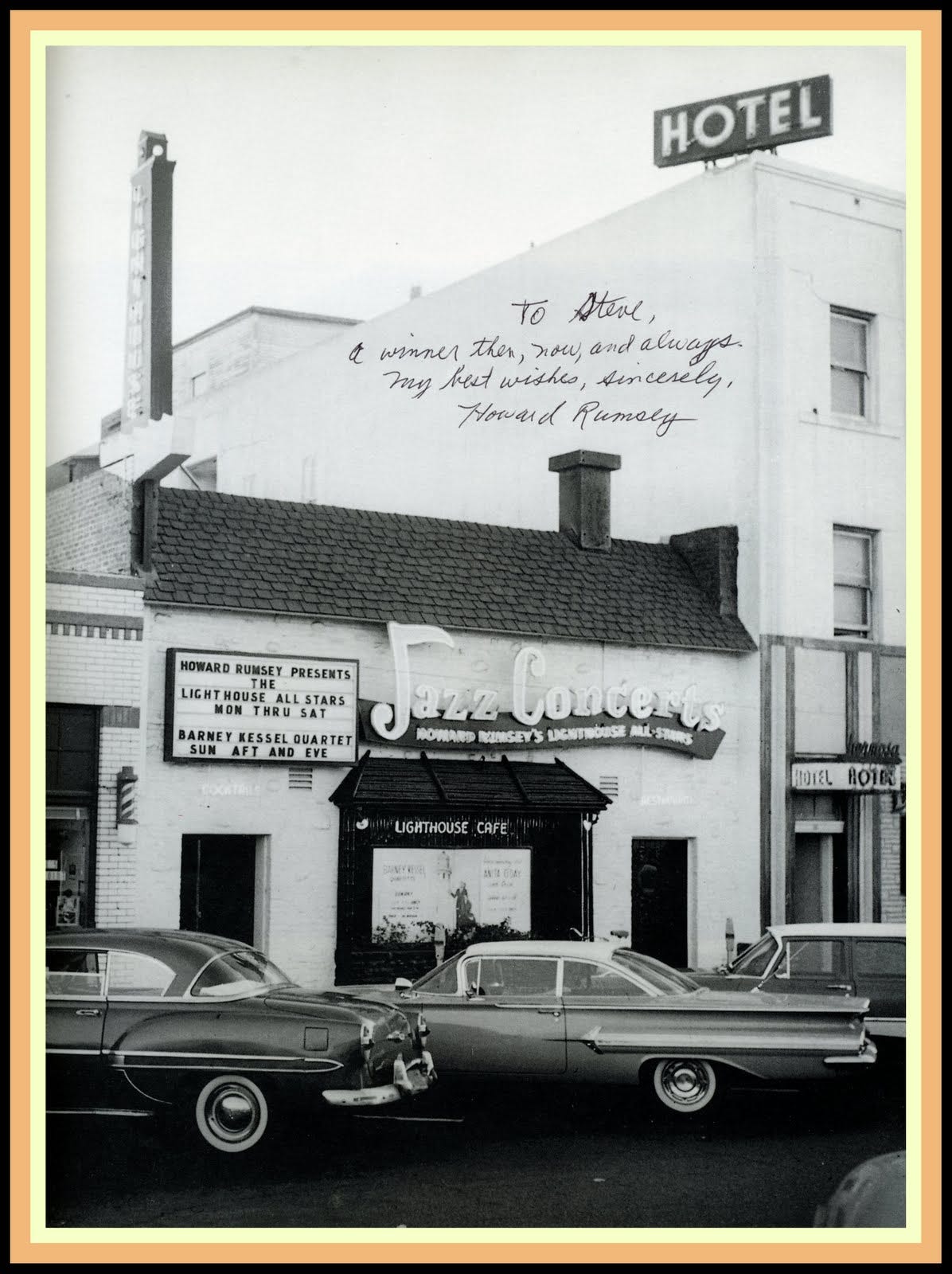

The Lighthouse All-Stars

In the early 1950s, in Hermosa Beach 20 miles south of LA, The Lighthouse Jazz All-Stars were formed. Originally with regulars bassist Howard Rumsey, saxophonist Bob Cooper, trumpeter Conte Candoli, and drummer Stan Levey, later All-Stars would include trumpeter Shorty Rogers, saxophonist Jimmy Giuffre, pianist Frank Patchen, and drummer Shelly Manne. The All-Stars also featured many great guest musicians like Max Roach, Miles Davis, Chet Baker, Gerry Mulligan, Bud Shank, and many more.

Check out this very short and informative video about this cool, California beach club: The Lighthouse.

Here’s what you would have heard live at The Lighthouse in 1953:

The Lighthouse became the LA jazz club and was famous for its Live Jazz on Sundays.

Live Jazz on Sundays was supplemented by a format where Rumsey played jazz records on weeknights. Eventually, the club adopted an all-live jazz policy with a stable of musicians that rotated according to their availability. Here was the idea:

Long, improvisational sets that will be as much for the musicians as the audience. No cover charge. No drink minimum. Just think of all those folks coming off the beach looking for a place to hang!

Dave Brubeck Quartet

In 1949, California native, Dave Brubeck helped form Fantasy Records in San Francisco. Along with Paul Desmond, he organized the Dave Brubeck Quartet in 1951. They took up a long residency at San Francisco's Black Hawk nightclub and gained great popularity touring college campuses, recording a series of albums with such titles as Jazz at Oberlin (1953), and Jazz at the College of the Pacific (1953). All this came well before they really hit the big time with Time Out, recorded for Columbia Records in New York in 1959. Paul Desmond, Joe Morello, and Eugene Wright were all stellar musicians in their own right. A little later in our journey, we’ll look deeper into bassist Eugene Wright, a Chicago native. In 1948, he put together his third and final incarnation of his Dukes of Swing band with pianist Sonny Blount as his music director. Sonny Blount was later to become known as none other than Sun Ra.

Richard Bock’s Pacific Jazz Records

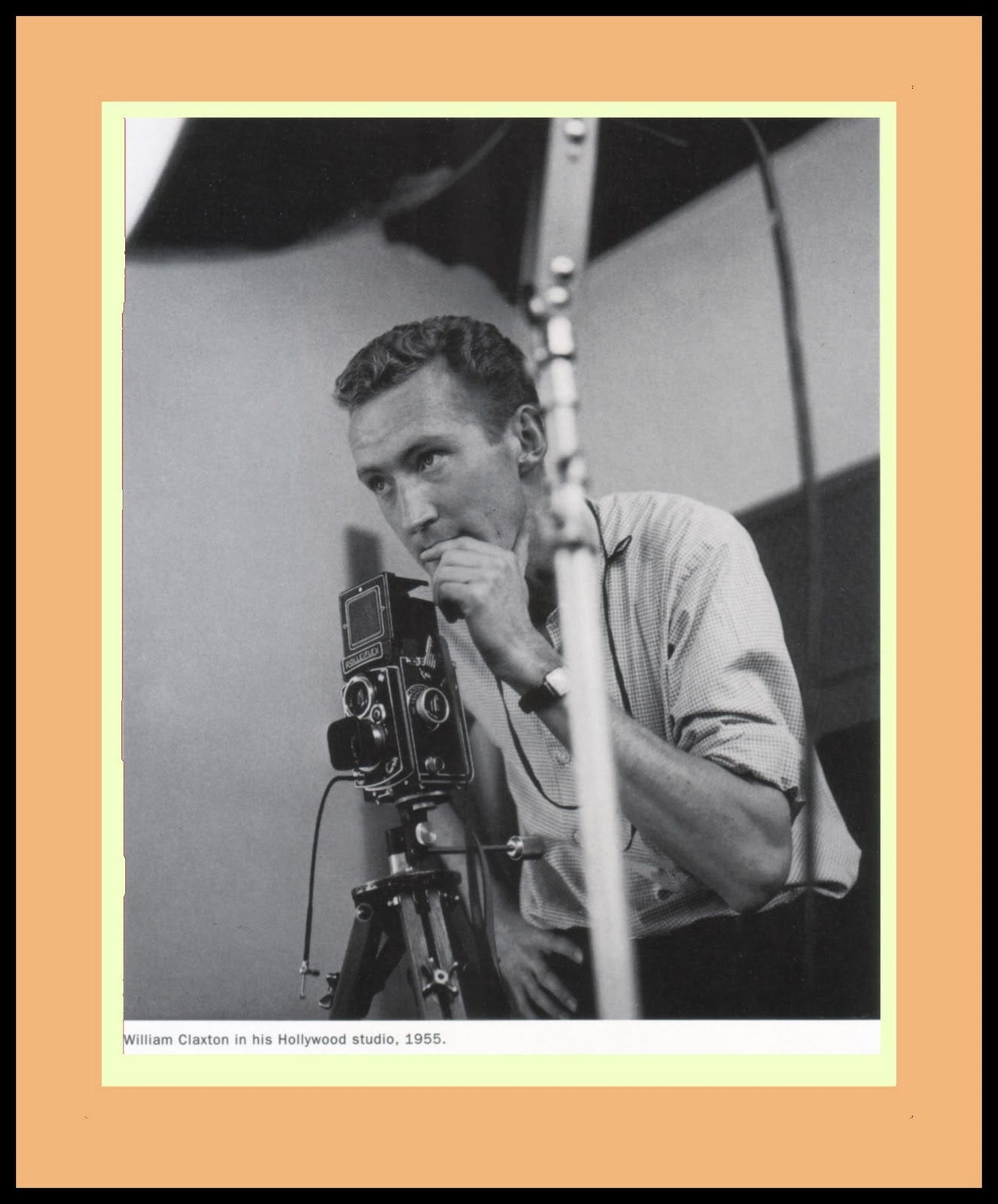

Richard Bock founded Pacific Jazz Records in LA in June 1952. At the time, he was handling publicity and off-night entertainment at The Haig, a small nightclub off Wilshire Boulevard. His vision in recording the West Coast Sound is legendary. And I will always associate the great photographer William Claxton with Pacific Jazz:

Ray Avery, a contemporary and another wonderful jazz photographer, once said of Claxton’s work: “Some of us take photographs of Jazz musicians, but Bill does much more than that: he is an artist with a camera.”

Here’s an interesting story told by Claxton:

In the Fall of 1952, I heard that Gerry Mulligan was going to appear in Los Angeles. I had heard interesting stories about this composer, arranger, and baritone player. I knew that he had written Jeru, Boplicity, Venus de Milo, and Godchild for Miles Davis and that he wrote for the Claude Thornhill Orchestra, but the best story about him was that when he was broke and no one would give him money to rehearse his band, he took the band outside to Central Park in the middle of Manhattan. This event caused a great commotion and did just what he wanted: to call attention to his talent and ambition.

Once again I borrowed my dad's car, grabbed my enormous 4x5 Speed Graphic camera, and pointed the big Packard towards the Wilshire district where The Haig club was located. Why this tiny converted bungalow was called The Haig, I shall never know. It was so small that its capacity was only 85 people. Shorty Rogers supposedly said of the place, "If you took four steps, you had crossed the room." There have been many stories of why there was no piano in the club. One was that Red Norvo had just appeared there and had it removed, having no need for it. Another rumor was that the owner of the club, John Bennett, hadn't paid the rent on it so it was taken back by its owner. Yet one more rumor was that the piano simply was not delivered. So Gerry Mulligan did what he does best: Improvise! So, along with Chet Baker, Chico Hamilton, and Bob Whitlock on bass, Gerry created the now famous "pianoless quartet."

It was opening night and I arrived early. After introducing myself to Gerry, I got permission to take pictures. The music was, of course, wonderful and the place was packed. While I was shooting pictures, a young man introduced himself as Dick Bock. He was recording the group and he asked if he could see my pictures as soon as possible. I asked, "Oh, do you have a record company?" He replied, "No, but I will have one by morning." He was so bright-eyed and optimistic. That was the beginning of Pacific Jazz Records.

Add in some important help from Roy Harte, and the rest is history…. Here is a Claxton photo from that session:

Lester Koenig’s Contemporary Records

Les Koenig's Contemporary Records, founded in 1951, and his earlier Good Time Jazz releases were as distinctive as Blue Note's. They were carefully and beautifully packaged, precisely and impeccably annotated, with covers and liners having a style all their own, and perhaps most importantly, expertly engineered by Roy DuNann, who joined Contemporary in 1956.

Here’s an interesting story about Les as told by JazzProfiles’ Steve Cerra on the one occasion, as a teenager, when he met him:

For some reason, I blurted out that I was also a fan of the many Firehouse Five + Two LPs and other traditional Jazz recordings that he had produced for his Good Time Jazz [GTJ] label.

Les seemed pleased by my interest in “Dixieland Jazz;” surprised that someone of “the younger generation” even knew about such music let alone his GTJ recordings of it.

In order to ward off any further embarrassment, I explained that it was really my Dad who liked Dixieland and that I just happen to catch it when he played these recordings at home [the implication being that I was just being respectful of my father’s taste in music].

About a week later, the (high school) Band Director asked me to stick around following one of the many music classes in which I was enrolled.

He handed me a big package with Good Time Jazz stamped on the mailing label.

“I think this is for you,” he said.

The package included about a dozen albums by the likes of Kid Ory’s Creole Jazz Band, Bob Scobey’s Frisco Band, Lu Watters’ Yerba Buena Jazz Band, and, of course, The Firehouse Five + Two.

The card inside was addressed to me and said: “For Your Dad. I hope HE enjoys the music. Best wishes, Les.”

And, yes, the “HE” on Lester’s card was capitalized to emphasize it as a tongue-in-cheek reference to me.

Les even had the amazing vision to record Ornette Coleman when Coleman could not get a gig anywhere in LA. Coleman’s historic first album, Something Else!!!! (1958) and Tomorrow is the Question (1959), were recorded by Roy DuNann for Contemporary. And the rest is history….

Next week, we’ll take the street car out of downtown and head south to take a little walk down LA’s Central Avenue….

I wish you all a very Happy New Year!!

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey, please share my newsletter with others - just hit the “Share” button at the bottom of the page.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that….

Until then, keep on walking….

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rI7hArFCiR8

I'm convinced that none of us would know Brubeck if it weren't for Desmond. Do you agree?