Oliver Lake

Heavy spirits...

In terms of playing music, there was no choice. We were chosen to play music. It wasn’t that we could do something else.

-Oliver Lake

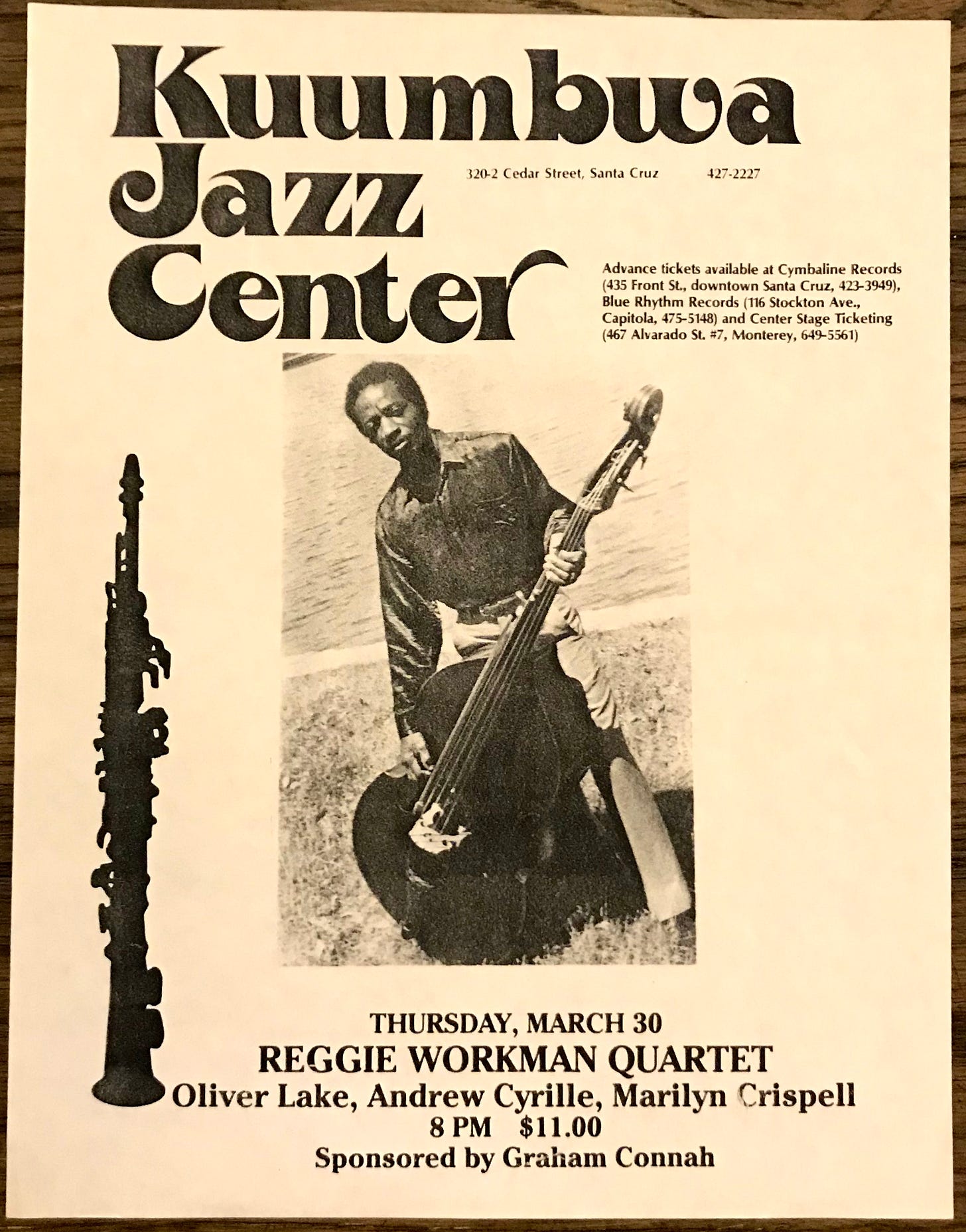

The first time I saw or even heard of Oliver Lake was in 1989 at the Kuumbwa Jazz Center in Santa Cruz, California; however, it was Marilyn Crispell I went to see. She was playing with the Reggie Workman Quartet:

After the show, they all signed their Synthesis album for me:

The Reggie Workman Quartet's tour out west came a couple of years after Synthesis was released late in 1986 on Leo Feigin’s label, Leo Records. I wrote about Feigin here:

Up until then, that concert was one of the most memorable I had ever attended. It marked the beginning of my journey into the deeper waters of that Big River called Jazz.

I first read about Marilyn Crispell the year before, while I was stationed in Germany. The Wire magazine’s May 1988 issue had a book review of Graham Lock’s Forces in Motion, which covers the Anthony Braxton Quartet’s 1985 England tour. During this tour, Lock joined the quartet’s entourage and wrote about all their concerts (maybe 18 of them in all?) and, in between, spoke to the musicians not only about jazz, but also their personal problems, and their views of life. It’s a fascinating book.

Although I went to see Marilyn Crispell that night in Santa Cruz, it was Oliver Lake who caught my eye, or I should say, ear. I left thinking, “Man, who was that?”

The week on that Big River called jazz, we’ll dip our paddles into the world of Oliver Lake.

Oliver Lake was born on September 14, 1942, in Mariana, Arkansas, but grew up in St. Louis, Missouri. In his youth, he played percussion and joined a drum and bugle corps. In a 1976 Coda magazine interview, he recalls his earliest musical memories:

There was a drum and bugle corps I was part of called the American Woodmen… I played the cymbals and bass drum. They didn’t play saxophone in the drum and bugle corps, but outside of that, [older musicians] were interested in jazz—which really tweaked my interest. I would tape their jam sessions and eventually picked up the saxophone.

In the Spring 2025 issue of A Magazine By We Jazz, Lake shared:

My mother owned a restaurant, and the jukebox was going there, and she sang spirituals. I can remember hearing her singing spirituals when I was a kid… Those neighborhood memories are with me from a musical standpoint. I met players, young musicians, who were into jazz, and that got me interested, going to some of their jam sessions and so forth. That really piqued my interest in wanting to play saxophone.

At the age of nineteen, he began playing the saxophone.

By 1965, he was working in a rhythm and blues band with Lester Bowie and Philip Wilson, and also played in a local blues band. In 1967, Lake formed a group, the Lake Art Quartet, which debuted at the Circle Coffee House in LaClede Town, a federally funded, mixed-income housing complex in St. Louis.

Texas saxophonist Julius Hemphill had settled in St. Louis while attending Lincoln University, and along with playwright and poet Malinké Elliott, they got together with Lake to discuss forming a cooperative to help facilitate wider exposure and more playing opportunities. Lake recalls a meeting they had after returning from a Chicago visit, “In our meeting, I suggested that we become a branch of the AACM. Julius then suggested that we form our own group, which included all the artists we had been associated with: poets, visual artists, dancers, and actors.”

And with that, in 1968, The Black Artists’ Group, Inc. was formed as a non-profit organization. They soon received major grant funding from the Danforth and Rockefeller Foundations. In July 1969, BAG agreed to pay $1 annual rent for a building at 2665 Washington Blvd., which became the BAG Artists-in-Residence Training Center:

It was here, inspired by the AACM, that BAG brought together and nurtured local Black experimentalists in the arts. For a more in-depth read on BAG, I wrote about it here:

Oliver Lake was a driving influence on BAG’s first album release, Ofamfa: Children of the Sun, most likely recorded in late 1971 and released in 1972 on their own Universal Justice Records label. Ofamfa was the first of four important BAG releases in the early 1970s. It was followed by two more releases Lake performed on as part of the Human Arts Ensemble: Whisper of Dharma (1972) and Under the Sun (1974).

Also in 1971, Lake recorded the historic album Ntu: Point from Which Creation Begins. It was recorded in St. Louis and was supposed to be Lake's debut as a leader. He planned to use it as the basis for a European tour with the group. However, the small label that intended to issue it went out of business, leaving Lake to try to find another record company willing to release it. The album was finally released by Arista/Freedom in 1976 after Lake had moved to New York City following his trip to Paris.

In 1972, at the recommendation of Lester Bowie, BAG traveled to Paris and used the Art Ensemble of Chicago's agent upon arrival, who arranged a live studio recording for French radio. This tape was released in 2024 by the Wewantsounds label as For Peace and Liberty.

The following year, the group recorded In Paris, Aries 1973, until For Peace and Liberty, the only album ever issued under the BAG name. Incidentally, the zodiac reference in the album title is a tribute to bassist and group member Kada Kayan, to whom the album is dedicated, and who fell ill and died before the group left for Paris.

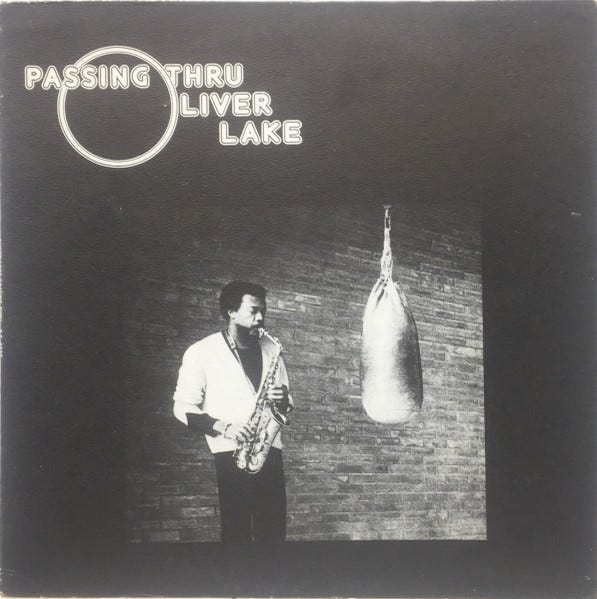

Before leaving Paris, in May 1974, Lake recorded Passing Thru, his first album as a leader, released on the French Africa Publishing label. In 1975, it was re-released in the U.S. on Passin’ Thru Records:

In September 1974, after two years in Europe, Lake returned to the United States and moved to New York City, where he began recording a string of excellent albums starting in January 1975 with Heavy Spirits, released by Michael Cuscuna on the Arista label. I love the diverse and adventuresome nature of this album which features Lake playing in different settings: three quintet tracks with Olu Dara on trumpet, Donald Smith on piano, Stafford James on bass, and Victor Lewis on drums; three more tracks with Lake backed by three violinists; a trio piece with trombonist Joseph Bowie and drummer Charles "Bobo" Shaw; and a solo sax piece.

In the 1976 Coda interview, Lake shared the circumstances surrounding his link-up with Cuscuna and Arista:

I was in Europe for two years, and as a result of being there - I had never spent any time in New York - but as a result of being in Paris my name had gotten to New York, to various musicians and so forth. So when I moved to New York in September 1974 Lester Bowie was there, and he turned me on to Michael Cuscuna, who strangely enough wanted to be in touch with me anyway about some deals, so I was looking for him and he was looking for me.

One of Lake’s first New York sessions, before he recorded Heavy Spirits, was as a sideman on Anthony Braxton’s New York, Fall 1974 album, produced by Cuscuna. He recorded on one song from that session, the saxophone quartet 30-EGN (Opus 37):

The interesting thing about this track is that it is a precursor to the World Saxophone Quartet, with three of the four saxophonists present here and all three from BAG in St. Louis: Lake on tenor, Julius Hemphill on alto, and Hamiet Bluiett on Baritone. Californian David Murray would replace Braxton in 1977 as the fourth saxophonist in the World Saxophone Quartet. This song served as an introduction for Lake, Hemphill, and Bluiett to the New York scene, as they were all still relatively unknown musicians.

In March 1976, at Generation Sound Studios in New York City, Lake recorded Holding Together. It was released the same year on the Black Saint label. The album featured the underrated musician Michael Gregory Jackson. From that album, here is Ballad, a beautiful song written by Jackson:

You can listen to the entire album here.

In August 1976, Lake returned the favor by recording on Jackson’s excellent album, Clarity, released on the Bija label. From that album, here is the title track, an incredible acoustic guitar, tenor sax, and flute trio:

David Murray plays tenor on this album. Following the Jackson Clarity session, in 1977, Lake co-founded the World Saxophone Quartet with Murray, Julius Hemphill, and Hamiet Bluiett.

The first time I saw the World Saxophone Quartet was in 1989, after they released Rhythm and Blues on the Elektra/Musician label. It was through the World Saxophone Quartet that I discovered the music of David Murray, whom I wrote about here:

In the late 1980s, along with bassist Reggie Workman and drummer Andrew Cyrille, Lake formed the group Trio 3. According to Lake, "We did it so much, we decided it made sense for us to have one group. It was a business decision, but also a musical decision.” The trio existed for roughly 35 years before disbanding in February 2022. The group's final performance took place in February 2022 at Dizzy's Jazz Club at Lincoln Center in New York City. I wish I could have been there! Here’s a video from one of those performances:

In 1988, Lake performed together with Frederick Waits and bassist Reggie Workman on pianist Mulgrew Miller’s strong album Trio Transition with Special Guest Oliver Lake. Recorded at A & R Recording in New York City in June 1988, it was released by Japan's label DIW Records. You can listen to this album here. It was the following year that I’d first hear Lake play at the Kuumbwa Jazz Center in Santa Cruz.

Here is one more for the road, actually three more. On May 5, 1978, at Blue Rock Studio in New York City, Lake recorded on Michael Gregory Jackson’s wonderful and underrated Karmonic Suite album. It was released the same year on Paul Bley’s Improvising Artists label. From that album, here are three classics that seem particularly relevant in these times. The first is Karmony (Love for Life):

…the second is Spirit with Lake on some righteous flute:

…and finally Spirit (Afterthought):

In 2014, Oliver was honored with what is arguably the greatest recognition of his artistry and vision to date, becoming one of only nineteen appointed for the prestigious Doris Duke Artist Award, a multi-year grant awarded to American artists in the fields of jazz, theater, and dance. That year, both Roscoe Mitchell and Randy Weston were also appointed.

The artistic scope of saxophonist, composer, painter, and poet Oliver Lake’s half-century-long career is remarkable. In a recent interview with We Jazz, Lake shared, “The legacy of BAG is self-determination and always knowing that you can accomplish your goals. Whatever you think of, you can achieve.” This is also the legacy of Oliver Lake himself, one of America’s true artistic masters and an example for all of us.

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of Jerome Kern’s song All the Things You Are.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Thanks for your Articles.