Reinbert de Leeuw died on February 14, 2020. Here is de Leeuw playing Erik Satie’s Sonneries de la Rose+Croix - Air du Grand Prieur.

I learned of Reinbert de Leeuw from one of my Dutch teachers at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, who recommended him to me: “If you get the chance, go listen to Reinbert de Leeuw play Erik Satie.” Unfortunately, I never did get to see him play live, but I kept my eyes open for him and became a big fan over the years. I’d like to share a little bit of his story in our journey across the pond to the 1991 North Sea Jazz festival.

In 1917, Erik Satie along with Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger and Germaine Tailleferre formed les nouveaux jeunes. Satie aligned the group against modern classical music coming from Wagner and Schoenberg’s Second Viennese School. However, shortly after forming the group, in September 1918 Satie discreetly left it and associated himself with pre-war French avant-garde painters and poets like Francis Picabia, Tristan Tzara, and other proto-dadaists.

When Satie left the Les nouveaux jeune Georges Auric , Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger and Germaine Tailleferre were joined by Darius Milhaud and Francis Poulenc to form Les Six.

Le Groupe des six, 1922, painting by Jacques-Émile Blanche.

This group would share Satie’s feelings for the overbearing late-Romantic musical styles of Wagner and Schoenberg; however, they had similar feelings for the impressionist music of Debussy and Ravel. This perhaps is where Satie drew the line.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Debussy and Schoenberg were moving in two different musical directions. In comparing them, I see the opposition between France and Germany, between impressionism and expressionism, between tradition and revolution. In the end, Debussy won the day. To my ears, the music of Satie and Debussy just sounded more appealing and by and large contemporary classical music has followed more their lead.

In the late 1960s, a similar musical confrontation was brewing in the Netherlands. The Dutch baby-boomers felt American jazz had become stagnant, as had its largely imitative Dutch variety. To mark their independence, younger Dutch musicians dropped the word jazz altogether and replaced it with the term improvisatiemuziek (improvisation music).

Stretching Jazz Conventions

November 17, 1969 marked an important event in the pursuit to restructure musical life in the Netherlands, when the Notenkrakersactie (Nutcrackers’ Action), a group of conservatory students, composers, musicians, and other artists disrupted a concert at the Concertgebouw Orchestra. These protagonists, in the spirit of Les Six, were motivated by a quintet of young musicians known as The Five, all of them Kees Van Baaren’s composition students at the Royal Conservatory in Den Haag. They were Louis Andriessen, Misha Mengelberg, Peter Schat, Jan van Vlijmen, and Reinbert de Leeuw.

The name itself, Notenkraker, is revealing. Besides the pun on Tchaikovsky’s famous ballet, The Nutcracker, noten in Dutch means both nuts and musical notes and kraken refers to the contemporary squatters’ movement in Den Haag and their semi-legal ambition to reclaim abandoned buildings for public use, an action that coincided with the rest of the countercultural movements and “happenings” in Amsterdam at that time.

These Dutch musicians were looking for new ways to develop and expand the Jazz idiom, most notably through an eclectic practice of collective improvisation. From the early experiments with free jazz, a distinctive Dutch jazz practice evolved that came to be known as improvised music. This particular scene developed in Amsterdam around key musicians such as Willem Breuker, Han Bennink and Misha Mengelberg, who were all experienced jazz players no longer satisfied with the conventional bebop combos and big band sounds. They were looking for a new sound. From the start, the Dutch improvisers collaborated intensely with non-Dutch musicians and became part of a transnational movement of musicians who were moving away from conventional jazz playing. For example, the Globe Unity Orchestra was deliberately aimed at transcending geographical and socio-cultural boundaries.

This transnational cultural exchange further politicized and isolated the improvisation music movement, which encouraged the formation of collective labels with means and channels independent of the large, established record labels in Europe. In this regard, Dutch improvising musicians created an extraordinary number of independent record labels for their music - between 1968 and 1989, there were at least 27. My favorite is the Instant Composers Pool.

In 1966, Willem Breuker, Han Bennink, and Misha Mengelberg founded the Instant Composers Pool, or ICP, the first Dutch collective to experiment with large-scale group improvisation. Initially started as an independent record label, ICP performed for the first time as a five-piece improvisation group on December 1, 1967 at the Utrecht club, Persepolis.

Here’s a classic from a couple of the ICP founders Misha Mengelberg and Han Bennink:

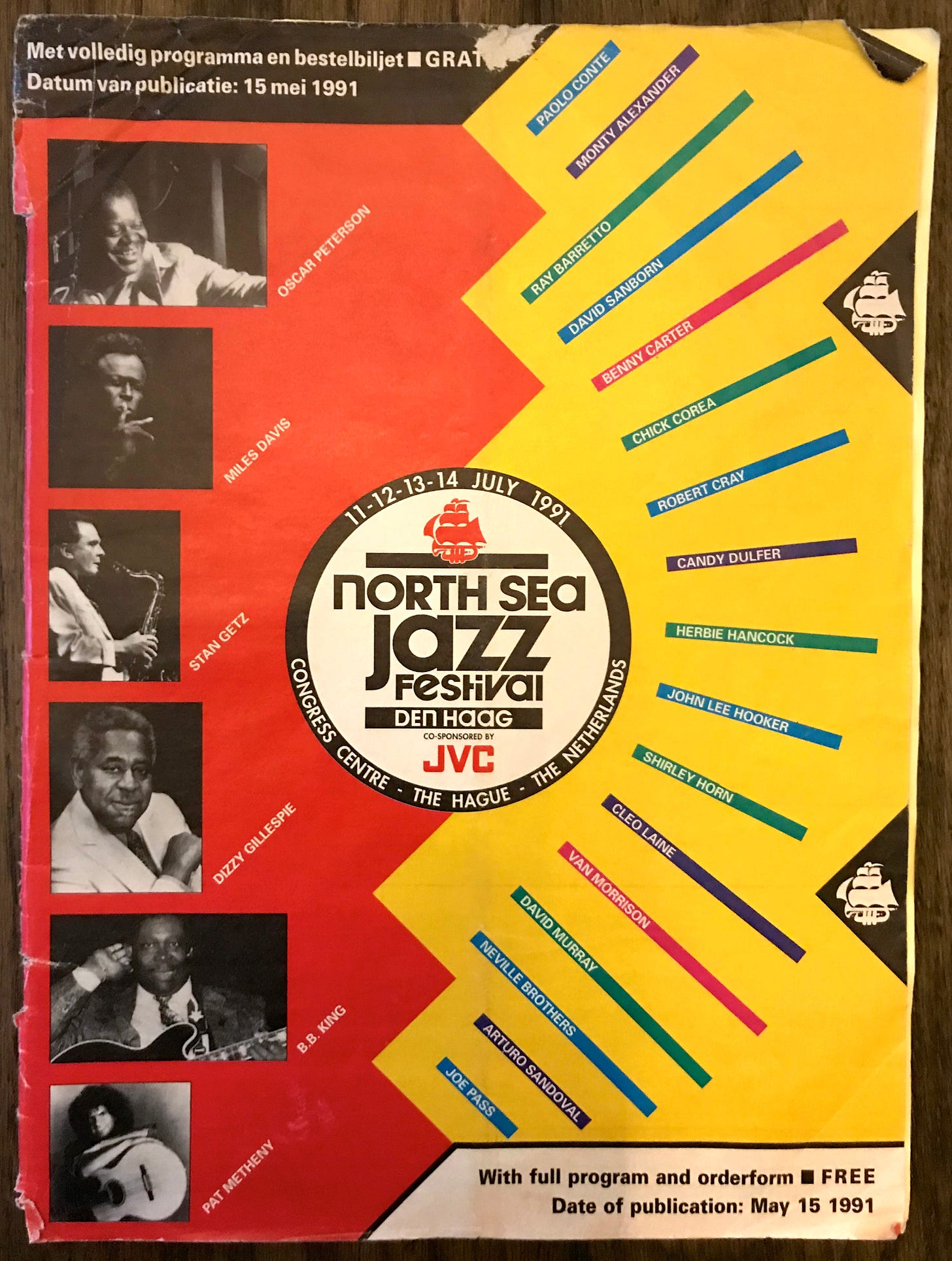

In 1991, my Mom and I took a trip to Denmark to visit the Karen Blixen Museum in Rungstedland and then headed down to Den Haag for the North Sea Jazz Festival. We had a great time messing around The Netherlands, and I still have great memories riding our bikes along the dikes out in Middelburg the morning before the festival. It was fun to go back to the festival again for the second time. Here’s my rather worn program from that festival.

The highlight for me was Friday night’s line-up at the Tuin Paviljoen: Charlie Haden’s Liberation Orchestra; Ornette Coleman’s Prime Time; the Willem Breuker Kollektief; and topped off with Lester Bowie’s Brass Fantasy. Incredible. That day I was most looking forward to Lester Bowie, but ended up liking the Kollektief the best. The hometown favorites were on fire, with Willem one minute going off on the saxophone like I had never seen before and the next out in the audience shining shoes during one of the numbers. If interested, here is the Kollektief’s entire show from that night.

In many ways, the 1991 festival marked a turning point in my journey. It was like traveling a river and turning the bend to discover a large, beautiful body of water you did not know existed. I was aware of the Kollektief and to a small degree the ICP, but I was not aware of the greater transnational improvisational movement that occurred in Europe in the late 1960s. This was a movement that existed outside of the Free Jazz movement in America. From that point on, my perspective of Jazz widened. No longer American Jazz dominated, I now appreciated the color and flare other European musicians like Peter Brötzmann and Alexander von Schlippenbach brought to my journey.

Willem Breuker

1966 was an important year in the development of improvisational music in the Netherlands. A significant and controversial moment took place on June 14th, when Willem Breuker’s experimental piece Litany for the 14th of June, 1966 premiered at the Jazz Festival in Loosdrecht. The largely pre-composed performance consisted of an 18-piece orchestra playing against the backdrop of singer Sofia van Lier reciting newspaper reports on the suspicious death during riots of a protesting construction worker.

With its unconventional sound and social-political theme, the performance was unprecedented at a festival known for pigeonholing musicians into categories like Dixieland, modern jazz, or Hard Bop. This marked the first time a group of musicians/artists acted with pronounced commitment to social and political engagement fundamental to their activities.

Here’s an excellent and fascinating video-bio of Willem Breuker. The opening number is, in fact, from the 1991 North Sea Jazz Festival:

In 1974, Willem Breuker left the ICP to form his own group called the Kollektief. I remember stumbling onto the Kollektief for the first time at the 1989 North Sea Jazz Festival. After that, I began looking out for and collecting some of their music - when I could find it. While in California, I picked up this CD on Breuker’s BVHAAST record label. It remains one of my Kollektief favorites, with Vera Beths and the Mondriaan Strings.

Vera Beths is one of the most renowned Dutch violin soloists of the post-war generation, with a keen interest in contemporary music. She inspired composers such as Willem Breuker, Peter Schat, Louis Andriessen, and Philip Glass to write works for her. Here is a cool and rare insight into the great legend of Willem Breuker, as Vera Beths and Reinbert de Leeuw visit Willem Breuker’s house and are astounded by the size and scope of his compositions there.

For me, perhaps what I admire most about Willem Breuker’s Kollektief is the complete conviction and commitment the musicians had for their leader and his music. In this way, they remind me of the great American Jazz bands like Duke Ellington’s Orchestra and even more like Sun Ra’s Arkestra.

I’ll end this week’s journey with another favorite, a Kollektief’s more mainstream song:

Next week, we’ll return to sunny California and pick up where we left off and follow that Big River called Jazz to Saturn for the first time….

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey, please share my newsletter with others - just hit the “Share” button at the bottom of the page.

This is a reader-supported project. The best way to show your support is by a subscription. Free and paid subscriptions are offered.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that….

Until then, keep on walking….

Great stuff, Tyler. Your reference to Darius Milhaud was interesting. As you may know, he moved to the US, taught at Mills College, and was a huge influence on one of his students...Dave Brubeck. Dave even named one of his sons Darius.

new stuff to me, all of it....and loving it. I have the spotify playlist on regular play