Michigan - IO

Alan Lomax and me across “the Upper Country"...

I set my compass North, I got winter in my blood.

-Acadian Driftwood, The Band

Back in the Spring of 2000, I was changing jobs, moving from Chicago to Minneapolis. Instead of taking the standard Interstate 94 west, I decided to drive up into Canada and around Lake Superior. It was a dubious trek into the Pays d'en Haut, French for simply “the Upper Country.”

Pays d'en Haut was a territory of New France covering the regions of North America located west of Montreal, including most of the Great Lakes region and expanding west and south over time into the North American continent that the French had explored. The Pays d'en Haut was established in 1610 and depended on the colony of New France until 1763, when the Treaty of Paris ended New France, and both were ceded to the British as the Province of Quebec.

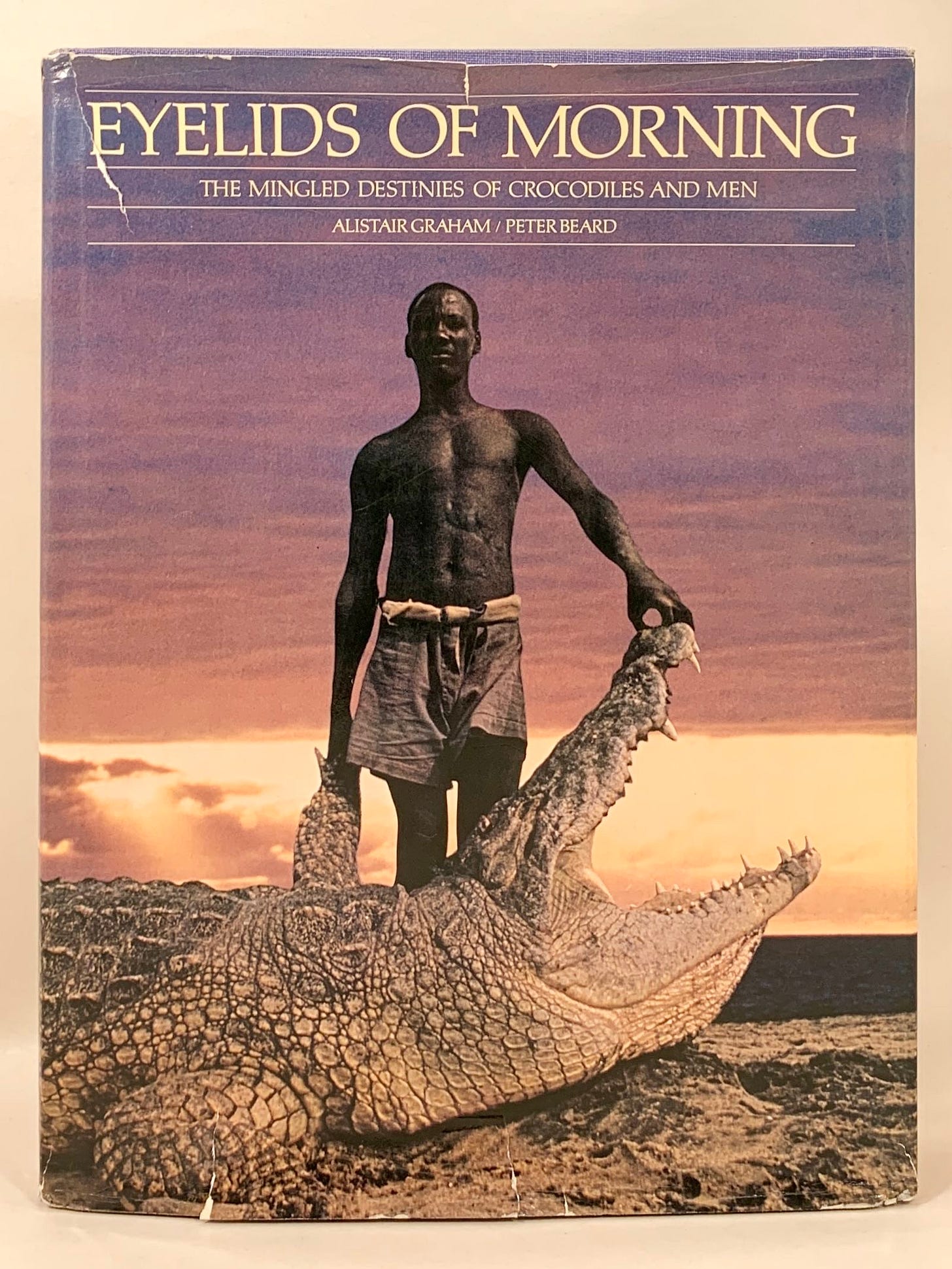

Before my trek, I had recently read William T. Vollmann’s book The Rifles. Not since I had read Alistair Graham’s Eyelids of Morning: The Mingled Destinies of Crocodiles and Men had a book stirred my desire for adventure.

Graham's book, with photographs by Peter Beard, chronicles their three years in Kenya researching the habits, history, and dubious future of one of the last great crocodile populations on earth.

With this in mind, Vollmann’s The Rifles could have been titled The Rifles: The Mingled Destinies of Native Americans and Europeans, as it chronicles his years in Canada researching the history of Sir John Franklin’s fourth Arctic voyage and his dubious search for the then-mythical Northwest Passage.

The Rifles, published in 1994, is the sixth volume in Vollmann's epic seven-book historical fiction series, "Seven Dreams: A Book of North American Landscapes,” which he started in 1990 with the first dream, The Ice-Shirts. As of now, five of the seven dreams have been completed - the fourth dream, The Poison Shirt, and the seventh dream, The Cloud-Shirt, are still unpublished.

After I read The Rifles, I read Vollmann’s even more compelling second dream, Fathers and Crows, released in 1992, which tells tales of encounters and conflicts in New France between French Jesuit missionaries, or Black Robes, and the native Huron and Iroquois peoples in Canada and present-day New York state.

After reading these two Vollmann books, like sirens, I heard the call of the Pays d'en Haut.

During my trek, I wanted to visit the sites Vollmann described in Fathers and Crows, such as Sainte-Marie among the Hurons, located near Midland, Ontario, on the eastern shore of Lake Huron. It was established in 1639 by the French and was their first mission north of the Great Lakes.

So off I went from Chicago east across Michigan to Detroit and into Ontario, around Toronto, and north to Barrie and Midland. After I left Sainte-Marie among the Hurons, I stopped at Algonquin Provincial Park, firmly in the Upper Country now, where I got lost chasing a moose through a beech tree forest. However, that’s a story for another day…

After I miraculously found the trail again, I continued further north up to Lake Nippising and then west to Sault St. Marie and around the northern shores of Lake Superior to distant towns called Wawa and Nipigon. Finally, I started to head southwest to towns like Pearl and Loon, and then south from Thunder Bay to the U.S. border near Grand Portage.

Along my way, I listened to the radio for hours and hours, and I picked up stations out of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, primarily WMTU, the college radio station out of Houghton, Michigan, which is affiliated with Michigan Tech University.

While driving on the north shore of Lake Superior on Highway 17, a major highway in Ontario, Canada, and a significant portion of the Trans-Canada Highway, WMTU was playing music from The Alan Lomax collection of Michigan and Wisconsin recordings, which documented French-Canadian and maritime ballads; bawdy lumberjack songs; Delta blues in Detroit; lyric pieces of Serbian, German, and Lithuanian origin; dance tunes played by Finnish accordionists and Native fiddlers, as well as occupational folklife among loggers and lake sailors in Michigan.

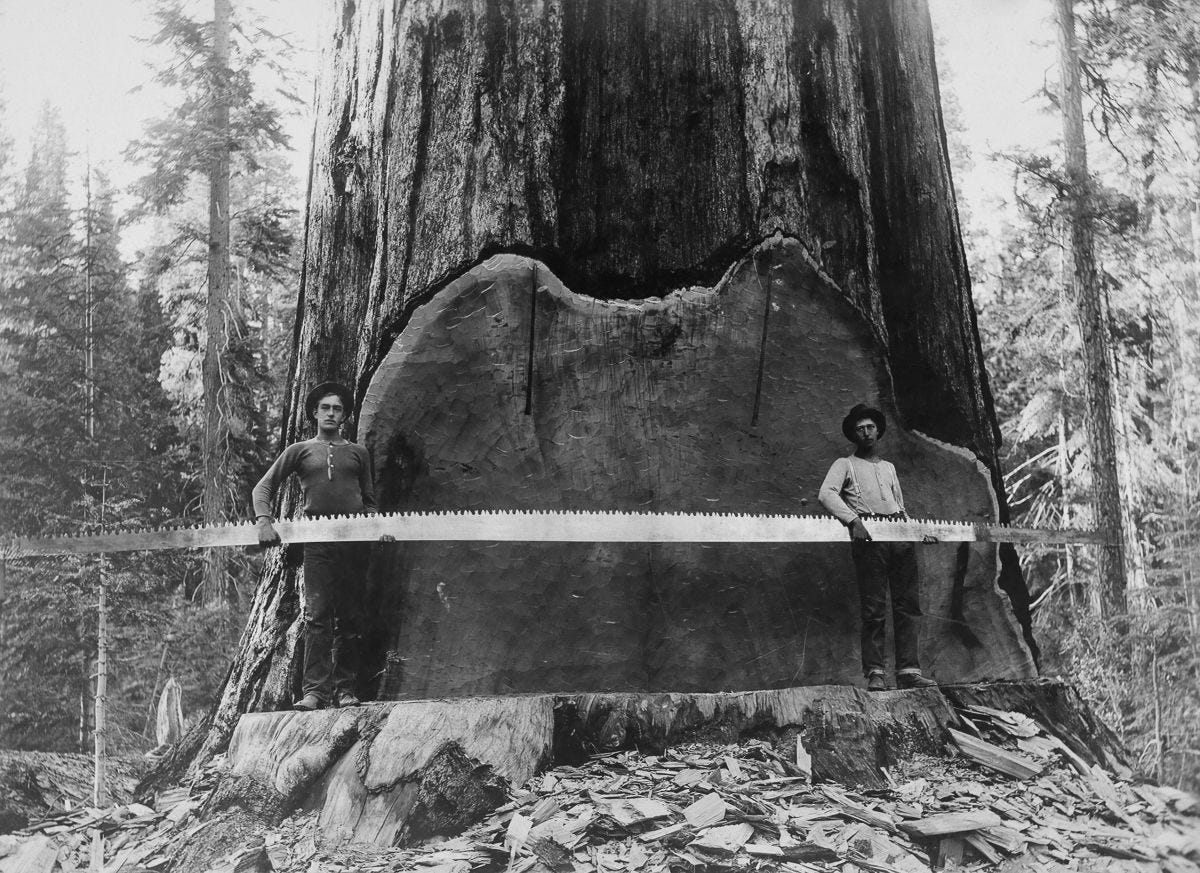

He visited pubs, front porches, and wherever people hung out, seeking out primarily the “old guys” who remembered work songs popular among the men who shipped ore and logged forests in the late nineteenth century. Folks like this:

It was the perfect soundtrack for my trek through the Pays d'en Haut.

Quietly over the years in the Upper Midwest, a folk-life that rivaled the South in content, perhaps eclipsed it in diversity. There, Europeans from dozens of countries had immigrated during the preceding decades, many to work in the booming lumber and mining industry in Michigan.

Alan Lomax's work documenting the music and lore of the rural American South is well-known. But few are familiar with the folklife survey he made in the Upper Midwest in 1938, when as a 23-year-old Assistant in Charge at the Archive of Folk-Song at the Library of Congress, he was dispatched on a three-month, three-state mission to survey folklife in the Upper Great Lakes across Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, although I don’t think he ever got to Minnesota, and pretty much entered Wisconsin at the end of the trip. The vast majority of his time was spent in Michigan.

When he returned nearly three months later, having driven thousands of miles on barely paved roads, it was with a cache of 250 instantaneous discs and eight reels of film documenting the incredible range of ethnic diversity and expressive traditions.

This week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the world of Alan Lomax’s 1938 trek through Michigan.

Before the Library of Congress sent him to the Great Lakes region, Alan Lomax had toured the country with his famous folklorist father, John A. Lomax, who had filled the library’s archive with stories and sounds primarily from the American South. Such “field trips” yielded thousands of recordings and stories from salt-of-the-earth performers, real-life cowboys, radical balladeers, and verbose and colorful raconteurs. However, the upper Midwest still stood as a great unexplored void.

So in August of 1938, in his 1935 Plymouth sedan, he set off intent on visiting rural communities to record their work songs and folk tunes on a large suitcase-sized Presto disc recorder powered by his car’s battery and a movie camera. Here’s the disc recorder:

Lomax’s itinerary took him from Detroit through the Saginaw River valley to the northern counties of the Lower Peninsula, including Beaver Island. Before the Mackinac Bridge opened in 1957, he used the Michigan State Ferry System, which provided an hour-long ferry ride across the Straits of Mackinac to the Upper Peninsula and into the far northern reaches of the Keweenaw Peninsula and then along the Lake Superior coast to easternmost Wisconsin.

In Detroit, he recorded in Hungarian neighborhoods and across town in solidly Serbian neighborhoods like Clairepointe, in the shadows of the Chrysler plant. On the way up north, he stopped for short stays in places like St. Charles and Mount Pleasant, where he recorded stories from Saginaw lumberjacks and a few tales about an emerging folk hero named Paul Bunyan. Then on to Posen, on the edge of Lake Huron, a town settled by Poles, where ballads were sung in Polish and fiddle tunes from the old country were still played. From there, he traveled to Charlevoix, at the edge of Lake Michigan, where he caught the ferry to Beaver Island, where the island’s Irish immigrants spun stories of Lake Michigan shipwrecks. Beaver Island was a common shipping stop in the Great Lakes, a safe port, and a source of wood for steamers.

On August 24, 1938, in Saint James on Beaver Island, he recorded fiddler Patrick Bonner. Here’s Bonner playing Black Tar on a Stick and Up and Down Broom:

Here’s Bonner pictured in the 1950s:

The son of an Irish immigrant, he was born in 1882 on “America’s Arranmore,” the nickname for Beaver Island that references the small island off the coast of Donegal, Ireland, the home for most of Beaver Island’s early Irish settlers.

Although from an Island in the middle of Lake Michigan, Bonner was not an isolated fiddler. Not necessarily a remarkably skilled fiddler, he had a special connection to the past and learned from the Island’s first generation of Irish fiddlers.

Lomax would spend five weeks in all in the Upper Peninsula, entering at St. Ignace and moving west through small towns like Newberry and Munising all the way to the Keweenaw Peninsula, jutting wildly out into Lake Superior. He gathered recordings all along the way.

For example, here are two French Canadian songs he recorded on October 13, 1938, in Baraga, Michigan, at the southeastern corner of the Keweenaw Peninsula.

On September 28, Lomax was in the center of the peninsula at Calumet, filming and recording Finnish Aapo Juhani and his healing practices, followed by a song on the accordion. You can watch this here at the 4:53 mark:

In early October, he left the peninsula, traveling southwest through Ontonagon, Greenland, and Marinesco, Michigan, and finally to Wisconsin. Short on time, he returned to Detroit, where he met up with bluesmen Calvin Frazier and Sampson Pittman, whom he had met briefly in Detroit in August.

During three sessions between October 15 and November 1, Lomax recorded them both in solo and duet settings. From the October 15 session, here is Frazier’s This Old Worlds in A Tangle:

According to a biography by Jason Ankeny, Fazier traveled to Helena, Arkansas, in 1930 and met Robert Johnson and Johnny Shines. The three men slowly journeyed north to Detroit, where they sang hymns on area gospel broadcasts. Then they returned south, where Frazier and Johnson joined with drummer James “Peck” Curtis in a string-band combo. Curtis was the drummer for Sonny Boy Williamson’s studio band, “The King Biscuit Entertainers” for the King Biscuit Time radio show out of Helena, Arkansas, in the 1940s. However, in 1935, Frazier was wounded in a Memphis shootout, which left another man dead. He fled back to Detroit and settled into a life of quiet anonymity, apart from gigs with Big Maceo Merriweather, Rice Miller, and Baby Boy Warren, before resurfacing for the Lomax recording.

At these Detroit sessions, Lomax also recorded Sampson Pittman on ten of his own original recordings, like Highway 61 Blues:

These were Pittman’s only known recordings.

Here are Frazier and Pittman playing together on I’m In The Highway Man, which was recorded in Detroit on November 1:

Lomax’s Frazier and Pittman recordings remained in obscurity until they were released in 1980 by Flyright Records on the album I’m In The Highway Man (1938 Detroit Field Recording).

Sampson Pittman died on June 10, 1945, in Saginaw, Michigan, and is buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Saginaw; however, without any tangible success recording or otherwise, Frazier nevertheless continued to perform around Detroit.

In 1949, he recorded with the Alben label, named after the first names of the founders, Al Smith and Ben Okum. Apollo Records distributed the short-lived Alben label. From that session, here is Be-Bop Boogie:

Frazier died of cancer in Detroit on September 23, 1972. He was 57 years old.

Here’s one more for the road. Lomax never did make a return trip to the region, though his work over the next half century, both in the United States and abroad, would make him the most renowned American folklorist of the century. Like Lomax’s own legacy, that of his recordings grows more important with each passing year.

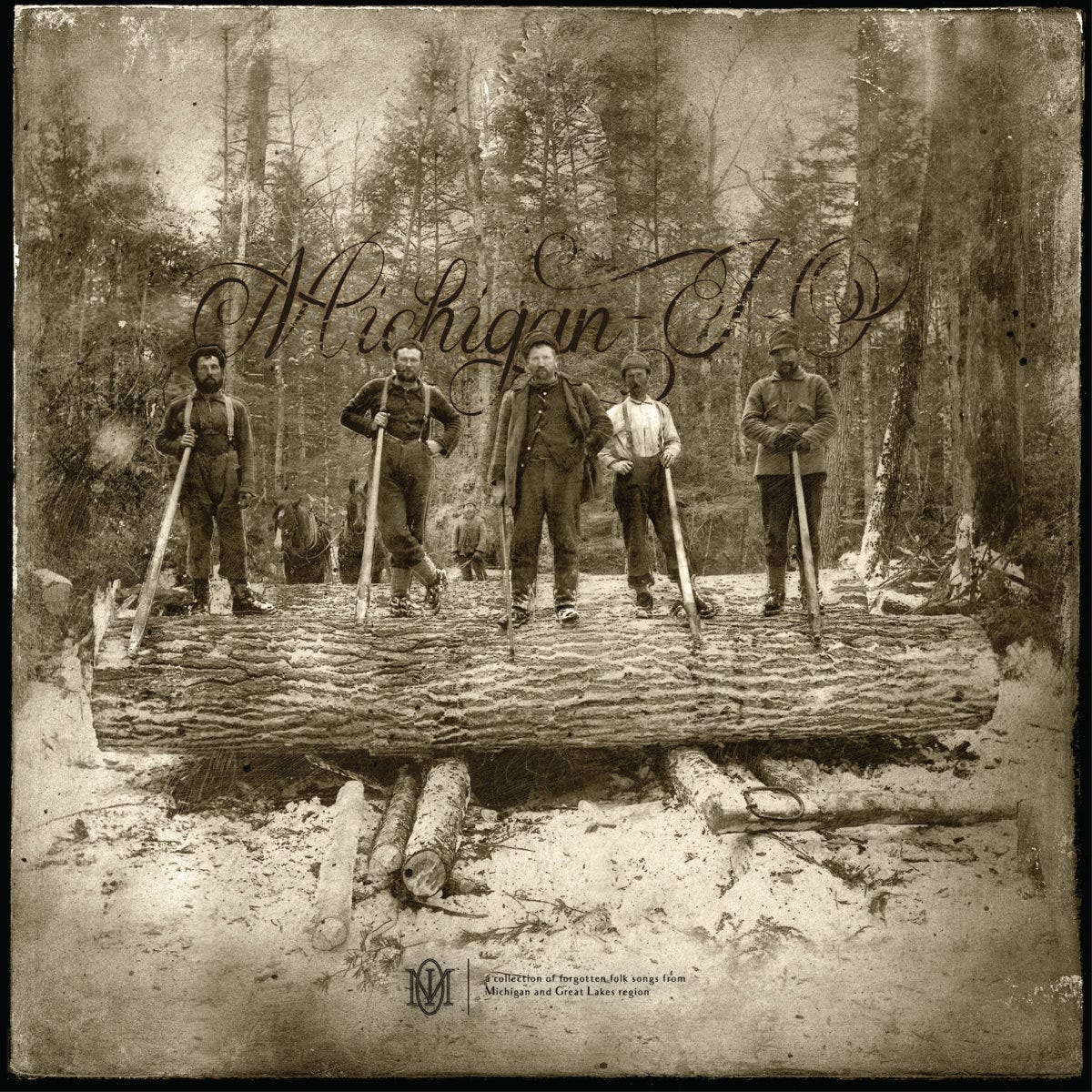

For example, when a bunch of musicians from Holland, Michigan, discovered the bygone 1938 Great Lakes field recordings of Lomax, they got a band together and decided to re-record them. The result was their 2019 debut album, Michigan - IO.

I love the vinyl’s label, which you can also see here:

In the Bandcamp description of the album, it is written:

In the 19th century, while the lumber and mining trades prospered in Michigan, so did the folk tradition. That’s owed mainly to the workers themselves, who, after a hard winter spent felling trees, or a dangerous voyage in a freighter filled with far too much iron ore, turned that pain and adventure into music. These very songs -- and many songs like them -- were sung throughout the Great Lakes region for decades, yet, in spite of their popularity, were rarely written down. They might have been lost for good, but for the work of a young song collector by the name of Alan Lomax… Now, more than eighty years after Alan Lomax’s trip, we here at the Audio Museum of American Song are proud to present this album as a tribute to the era, and a contribution to Michigan’s great folk tradition

Here’s the title track:

The group’s banjoist and guitarist, Andy Bast, said of these historic folk tunes:

We couldn’t believe there was all this material out there that many people haven’t heard of. We found a bunch of songs we loved, and we went up north to the Upper Peninsula and re-recorded them, reimagined them. We basically only do songs that were written before 1940, but they’re still new.

We think of it as a chain and we’re just one link in this chain. Maybe Alan Lomax was another link in this chain … where he found these songs that could have died out, and went into pubs and went on people’s front porches and had a huge recording rig with him in the ’30s. He was just an adventurer and found these people and had them sing into their microphone back then. Due to the Library of Congress, we heard them anew, and now we get to share them live.

Robert Lomax’s 1938 journey was a dubious trek into the Pays d'en Haut, filled with anxiety from exhaustion and loneliness. He was plagued by equipment failure and shortages of money to live on. Buying food and drinks for the people he recorded, sometimes staging parties for them, was an enormous expense. But he was dedicated to his cause.

As a result, we can now listen to Michigan’s early folk music, brought to the region by immigrants and played in the logging camps, mines, and factory towns where they worked. It’s all just another link in this chain on that Big River called Jazz, the music lives on…

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of the second of three parts on Tina Marsh and the Creative Opportunity Orchestra.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

I envy you your recent journeys, Tyler!

I once (2007) spent a week at an RV camp in Saline, Michigan. That week happened to precede a Bluegrass and Old-Time music festival (which I was unable to stay and attend) and more musicians showed up every night throughout the week. They’d jam for hours in the evenings and I wish I’d had a tape recorder with me!