There’s just a handful of things the radio is pushing, and they keep playing the same stuff over and over, just like commercials. They are commercials, and the only alternative is to turn them off and turn on to something different, as long as it relates to where people are at in their daily lives. That’s what we are trying to do with Saturday Night Special, and we just hope people will get something out of it they can use.

-Lyman Woodard

I was down in Kansas City a couple of weeks ago visiting a friend - Trombone Steak. We went out on the town looking for music.

We found it first on Friday night at a KC house party on the West Side. Four bands played only David Bowie covers. Classic. Then on Saturday, we found it at Knuckleheads in East Bottoms where the Reyes Brothers from Stranded in the City hosted an open mic session that was fantastic in its variety and overall musicianship. Then we headed downtown and stopped at the Green Lady Lounge at Grand Boulevard and East 18th Street where Ken Lovern’s OJT was playing with Lovern hitting the Hammond organ hard. Here he is at the Green Lady:

That night, with stocking feet on the bass pedals and all, Ken Lovern brought it. I mean in the way that Lyman Woodard could bring it.

I thought OJT was great, which is kind of strange since I’m not a huge fan of organ trios or quartets. I cut my teeth in high school on the crazy organ from Brian Auger’s Oblivion Express. So later on, when I heard Jimmy Smith or Baby Face Willette, it was hard to get amped up no matter how good the horns were. When you hear Auger playing Eddie Harris’s Freedom Jazz Dance from 1970, it’s hard to go back:

The organ and guitar mix and the energy on this is very reminiscent of the stuff coming out of Detroit with Lyman Woodard, Dennis Coffey, and later Ron English, culminating in Woodard’s seminal 1975 album Saturday Night Special.

Recently, Mike Johnston, bassist from Northwoods Improvisers, and I were talking, and he described Woodard’s Saturday Night Special in this way:

For me, it's a dark, gray music album sound that has always reminded me of the streets of Detroit. Like most Detroit music its powerful and haunting. But something about this album is original with a lot of identity.

I then asked him how he’d describe the “Detroit” sound. He replied:

I believe that in many ways Detroit music was one of the main music that brought the drums to the forefront. From Elvin Jones in jazz, to Motown and hard rock. Detroit style is hard and dark - unafraid.

Admittedly, I’m not very well-versed in Detroit sound, but his comments intrigued me. So, I started to search for that sound and Woodard’s place in it.

This week on the Big River called Jazz we dig in our paddles to discover the world of Lyman Woodard.

Lyman Woodard was born in Owosso, Michigan on March 3, 1942. He started playing the piano at the age of three. He was a gifted pianist, but after hearing Jimmy Smith on those Blue Note albums, he took up the Hammond B3 organ. After high school, he studied at Flint Northern College for a year and a half and then took a six-month class in Toronto at the Advanced School for Contemporary Music, where his mentors were Oscar Peterson and Ray Brown.

He got his start around 1960 gigging at bars in Lansing, Michigan. Then he moved to Jackson and started gigging with tenor saxophonist Benny Poole. In 1964, Woodard moved to Detroit.

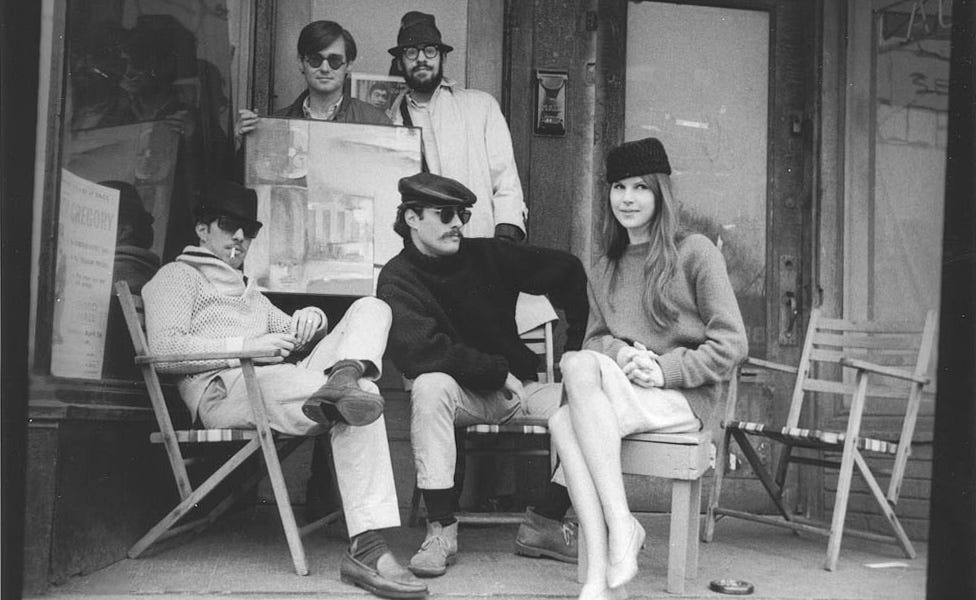

At a time when many musicians were going to New York City, San Francisco, LA, or Europe, Woodard decided to stay in Detroit and got involved with The Detroit Artists’ Workshop, an artist-controlled cooperative similar to the Jazz Composers Guild in New York City and the AACM in Chicago. The Detroit Artists’ Workshop was an important meeting ground for musicians and other artists at the height of the Detroit Free Press artistic movement.

The short-lived Red Door Gallery and the Detroit Artists’ Workshop were the first serious alternative, DIY, avant-garde, cooperative galleries in Detroit. The Artists’ Workshop was founded on November 1, 1964, by John Sinclair, Magdalene Arndt (Leni Sinclair), Charles Moore, George Tysh, Robin Eichele, and ten others who rented a performance space on the campus of Wayne State University.

This small independent group of poets, artists, and musicians inspired a cultural revolution that influenced the jazz music scene in Detroit.

One jazz group that formed out of the workshop was the Detroit Contemporary 5, which, in January 1966, took a ten-day tour of the East Coast. This fluid ensemble included John Dana, Ronald Johnson, John Sinclair, and trumpeter Charles Moore.

Here is a handbill from a series of concerts presented by The Artists’ Workshop from Detroit and the Jazz Art Music Society from Newark with the Detroit Contemporary 5, featuring Marion Brown:

This event highlights the intersecting networks of avant-garde jazz and radical politics. Ensemble member John Sinclair founded the White Panther Party two years later and played in the celebrated proto-punk band MC5.

Back in Detroit in August 1966, Sinclair was coming home from serving six months in prison for his second arrest for possession of marijuana, and the Detroit Artists’ Workshop threw a poetry and jazz party, as detailed on this poster by Leni Sinclair:

You can see The Lyman Woodard Ensemble on this handbill at the top, after the Detroit Contemporary 4. Unfortunately, another drug bust eventually put an end to the Detroit Artists’ workshop.

Soon after, Woodard became the Director and Arranger for Motown and toured with Martha Reeves. However, after the 1967 Detroit riots, Barry Gordy started the wheels rolling to move Motown to LA.

I wrote about that here:

The eventual departure of Motown in 1972 created a vacuum in the Detroit music scene. A few years later a new music scene started to emerge from two important artist-controlled collectives built on a creative outlook on urban self-determination and self-actualization.

In the aftermath of the devastating riots and with the help of John Sinclair, in 1969 pianist Kenny Cox founded Strata Corporation with its several operating divisions—most notably Strata Productions, Strata Records, Strata Gallery, Strata coffee house, and the non-profit affiliate the Allied Artists Association. Cox was already a leading figure in Detroit’s jazz scene, having recorded two Blue Note albums: Introducing Kenny Cox and the Contemporary Jazz Quintet; and Multidirection.

Along with Strata, another important collective was Tribe, founded in 1971 by trombonist Phil Ranelin, saxophonist Wendell Harrison, and Harrison’s first wife, Patricia. Others involved in the enterprise included pianist Harold McKinney and trumpeter Marcus Belgrave. Along with Strata, Tribe would grow into a legendary Detroit jazz collective that symbolized a growing black consciousness within the black community and specifically among artists.

It was from these community organizations that the Detroit sound Johnston spoke about found its footing. However, that sound was also developed by former Motown Funk Brother studio musicians like guitarist Dennis Coffey and bassist Bob Babbitt, whose playing lit up many hits in the 1960s and 1970s.

Babbitt’s signature bass line came in 1971 from a stellar solo on the pioneering funk-rock song Scorpio from Dennis Coffey and the Detroit Guitar Band’s album Evolution. Coffey described Babbitt’s bass as a “big and fat”:

Perhaps the highlight of Babbitt’s career is this Scorpio solo. Coffey recalled, “It set a bass standard. You didn't hear bass solos on records, let alone a hit record. Guys were freaking out trying to duplicate it. That was the benchmark for a bass player: You had to be able to play that Scorpio solo.'"

A few years earlier at Morey Baker's Showplace Lounge in Detroit, Coffey recorded a live trio session with drummer Melvin Davis that included Woodard. That session was released by Resonance Records in 2016 as Hot Coffey In The D. From that session here is The Bid D:

Then again in 1969 the Dennis Coffey & The Lyman Woodard Trio recorded the scorcher River Rouge on the short-lived Maverick label:

In 2014 drummer Leonard King's Uuquipleu Records produced and released Woodard’s Lost & Found album, which was recorded at Pioneer Studio in Detroit in 1971. From that release, here is Woodard’s Kimba:

In 1973, Woodard and guitarist Ron English formed the Lyman Woodard Organization. Their first release was Saturday Night Special, released on the Strata label in 1975:

The album cover photo was shot by Leni Sinclair. Word on the street is that she took it after a gig when Woodard emptied his pockets onto a coffee table.

Here is a review of the album from the May 23, 1974, Ann Arbor Sun:

Through the years the Motor City aesthetic has been embodied in the work of musicians as widely various as John Lee Lee Hooker, Aretha Franklin, Smokey Robinson. Bob Seger, Donald Byrd, Yusef Lateef, Elvin Jones, Martha Reeves and the MC5. With the departure of Motown Records to Los Angeles a number of years ago, however, the Detroit music scene was vacuumized. Yet through the last few years, a new scene has emerged, most particularly evident in the creative works emanating rom two artist-controlled record companies, Tribe and Strata.

One of the Strata groups has just released a fine album which could help regain Detroit ‘s musical recognition in a current sense. “Saturday Night Special” is the first release by the Lyman Woodard Organization, currently being heard on WJZZ in Detroit, WCBN in Ann Arbor and a number of other stations

From the album, here is Joy Road:

During this time, Woodard continued to record outside the organization.

On February 19, 1978, as part of the Composers’ Concepts series, Woodard played on Ron Eglish’s album Fish Feet. From that recording, here is the title track:

This song also features Marcus Belgrave and Phil Ranelin on horns and Leonard King on drums. Incidentally, the great Kenny Cox also appears on the album playing piano.

In 1979, Woodard started Corridor Records and released his second album with The Lyman Woodard Organization’s Don't Stop The Groove, a live recording at Cobb’s Corner in Detroit. The album featured Marcus Belgrave on trumpet:

From that album, here is the title track with Allan Barnes on tenor sax:

Here’s one more for the road. Lyman Woodard passed away on February 25, 2009. Per Woodard’s request, drummer Leonard King organized a tribute concert to honor him and acknowledge Woodard’s lasting impression on both Detroit and the many musicians he worked with. That concert took place in Detroit on March 3, 2010. It was released in 2011 on Uuquipleu Records. Here’s the introduction:

The announcement is by Leonard King, who according to Mike Johnston, “is still active and came to our last Detroit gig.”

Here is their version of Lyman Woodard’s composition Déjà vu:

In a December 9, 2020, interview with Wax Poetics, Leonard King shared, “If there’s anything I got from him directly, it is just to speak honestly; don’t tell any lies through music. He was a beautiful human being and an honest person, and I believe his music speaks of that.” A fine tribute and characteristics we can all aspire to in our music and life.

I might have gotten some of it wrong, but this is my interpretation of the “Detroit Sound.”

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of Larry Carlton.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel so inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Mr. King! Another great journey, thank you. Appreciate you turning me on to the bass solo on Scorpio. Killer!

Aw yeah, this is fantastic! Detroit’s got such a rich and somehow still unwritten history. Love the handwritten playbills.