From the time Louis catapulted onto the New York scene, everybody and his brother tried to play like him.

-Rex Stewart

When I was a child and overcome by excitement running through the woods by our house and down to the lake, I always dreamed of great adventures in faraway lands and rivers.

I played “army” in the woods, quietly moving deep behind enemy lines. I searched for rare butterflies, hunted frogs by the pond, and looked for salamanders under rocks.

It was a ritualistic thing.

Those days belonged to that lovely time when, to one discovering the world of nature, all things are new, wonderful, and deeply significant.

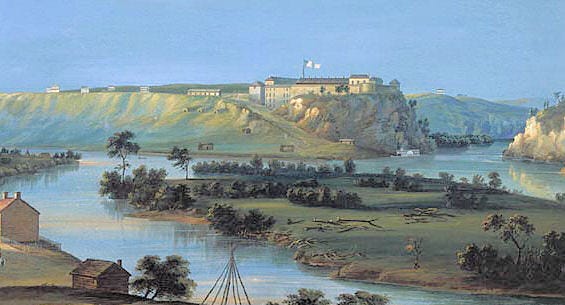

As I got older, still overcome by excitement, I discovered old Fort Snelling, the imposing and romantic fortress overlooking the entrance of the Minnesota River into the Mississippi River at Mendota, a Dakota word meaning “meeting of the waters.”

It was there that I discovered the Mississippi River. As I stood on its shores, it took my breath away.

The Mississippi River is a very different river now than it was when Native Americans living amid the forests of its vast valley, who knew nothing of other great rivers on earth, called it “The Father of Running Waters.”

In the summer of 1832, the American geologist Henry Schoolcraft followed the devious and narrow channels of the Mississippi River north of Cass Lake until he finally came to the water called Lac Labiche (Doe Lake). This, he felt, was the river’s true source; however, he wanted a better name for the spot. With the help of a missionary who knew Latin, they translated the word for “true head”—veritas caput—and reduced it to Itasca. With that, the source of the Mississippi River was declared here, at Lake Itasca near Bemidji in Northern Minnesota:

Just 25 feet south is the river’s first bridge - a log bridge:

The river then flows 2,340 miles into the Gulf of Mexico near New Orleans.

Almost 500 miles from Lake Itasca is a waterfall, which held cultural and spiritual significance for the native tribes that frequented and lived in the area. They called this portion of the Mississippi River hahawakpa, "river of the falls." Since the falls had to be portaged, the area became a natural resting place and trade point between the Dakota and Anishinaabe peoples.

However, in 1680, only 60 years after the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock, hahawakpa became known to the Western world when Father Louis Hennepin, a Belgian Catholic priest and missionary, saw them and published his observations in a journal. Through earlier writings, Hennepin had brought Niagara Falls to the world's attention.

Father Hennepin named hahawakpa the Chutes de Saint-Antoine or the Falls of Saint Anthony after his patron saint, Anthony of Padua. Here is an idea of what the falls looked like from Albert Bierstadt’s 1880 painting The Falls of St. Anthony:

The village of Minneapolis was incorporated in 1856 and merged with St. Anthony in 1872 to form the city of Minneapolis.

The Mississippi River was an important part of Minneapolis and St. Paul's growth, providing a valuable trade route for goods. The St. Paul District of the Army Corps of Engineers operates and maintains 13 locks and dams, beginning at Upper St. Anthony Falls in present-day downtown Minneapolis and ending at Lock and Dam 10 in Guttenberg, Iowa.

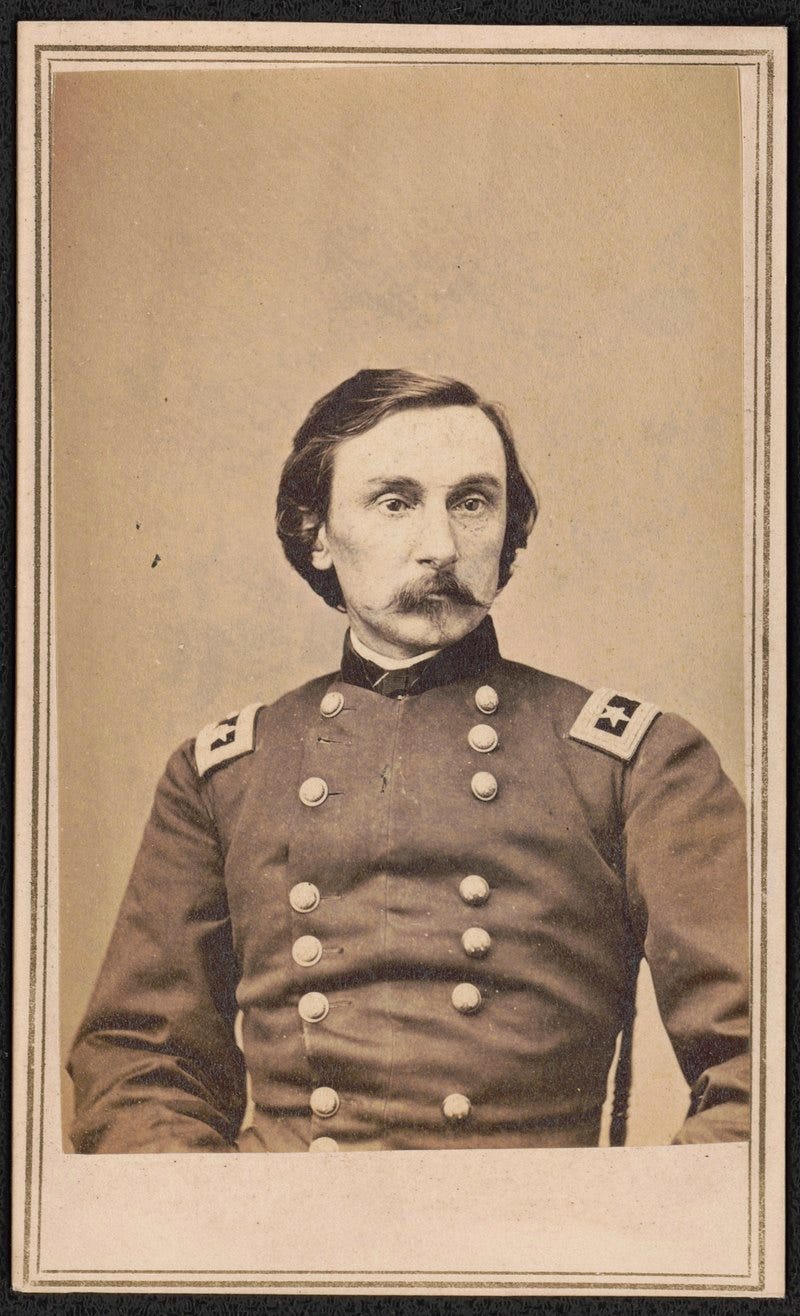

The St. Paul District's origins date back to 1866, when Congress authorized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to establish a 4-foot navigation channel on the notoriously unreliable Upper Mississippi River. Maj. Gouverneur Kemble Warren, a West Point graduate widely acclaimed for his leadership at the Battle of Gettysburg, was sent to St. Paul to open a district office and conduct preliminary surveys of the main river and its tributaries.

In 1907, the engineers built the first lock and dam, the Meeker Island Lock and Dam (formerly known as Lock and Dam 2). However, the Meeker Island Dam was demolished, and the larger Lock and Dam No. 1, or Ford Dam, opened in 1917. It is located between Minneapolis and St. Paul, right below old Fort Snelling.

Another important role of the Mississippi River was the spread of music, in particular, jazz music, which started to find its way up the river from New Orleans on rear-paddled riverboat steamers like the S.S. Sidney:

Here’s another photograph of the S.S. Sidney:

The ship was built in 1880 for Captain William M. List, who named the boat after his mother. In 1911, the Streckfus Steamers Company acquired it. They are believed to be the first operators to have a New Orleans jazz band play live on a Mississippi steamer.

Louis Armstrong was already a first-rate musician when he went to work for Fate Marable on a Streckfus Steamers in 1919. The following year, he made his first trip on the S.S. Sidney from St. Louis to Minneapolis and back. Here’s a photo of Marable’s band on the S.S. Sidney - that’s Armstrong fourth from the left:

This gig was a finishing school for Armstrong, where he perfected his craft under the instruction of Marable, who knew little about jazz but a lot about discipline.

This week on that Big River called Jazz we’ll dig in our paddles and explore the world of Louis Armstrong with the Fletcher Henderson band.

When King Oliver left New Orleans for Chicago in 1919, Louis Armstrong left the riverboat steamers and took his mentor Oliver’s place in Kid Ory’s band.

In 1922, Armstrong was invited by Oliver to join his Creole Jazz Band in Chicago. At the time, Chicago was the center of jazz, and Oliver’s band was the best and most influential hot jazz band in Chicago.

On April 5 and 6, 1923, Armstrong performed on Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band’s first recordings for Gennett Records, founded in 1917 in Richmond, Indiana, by the Starr Piano Company. Here’s a rendering of the Starr Piano Company, where Gennett Records was located:

The label flourished in the 1920s and also produced the Starr, Champion, Superior, and Van Speaking labels.

During that April 1923 two-day session, Armstrong played second cornet behind Oliver. Along with them were Honore Dutrey on trombone, Johnny Dodds on clarinet, Bud Scott on banjo, Baby Dodds on drums, and his future wife, Lil Hardin, on piano. From the session, here is Dipper Mouth Blues with Bill Johnson on vocals:

Armstrong quit Oliver's band in June 1924, no longer wanting to “play second fiddle.” He played around Chicago until he received a telegram from Fletcher Henderson to come to New York and join his band, the most important jazz band in New York City.

Interestingly, as good as his band was, Oliver’s music was unknown outside the urban ghettos. Unless you happened to live in certain parts of Chicago or New Orleans, Louis Armstrong was still relatively unknown.

On October 7, 1924, a few days after he arrived in New York City, Armstrong made his first recording with Fletcher Henderson and His Orchestra for the Columbia label. From that session, here is Shanghai Shuffle:

In his book Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, Terry Teachout wrote:

In May of 1925 Armstrong showed Redman “a little book of manuscripts, some melodies that he and the famous King Oliver had written in Chicago… He asked me, ‘Just pick out one you may like and make an arrangement for Fletcher’s orchestra.’” Redman chose “Dipper Mouth Blues,” renaming it “Sugar Foot Stomp” and arranging it in a way that fused Oliver’s loose, swinging sound with the yelping clarinets and quacking brass of the Henderson band.

Here’s Sugar Foot Stomp, Redman’s arrangement of Oliver’s Dipper Mouth Blues:

According to Don Redman, this was “the record that made Fletcher Henderson nationally known.”

Armstrong’s final performance with Henderson’s band was on October 21, 1925. From this session, which also included the great Coleman Hawkins, here is Carolina Stomp:

By this time, Lil Hardin was now Lil Armstrong and unmoved by her husband’s overwhelming success in Henderson’s band. She wanted to bring him back to Chicago, saying, “I want him to be featured… and I want his name out front.” After she secured a deal with the manager at Chicago’s Dreamland Cafe, she sent Louis a telegram: “COME BY STARTING DATE OR NOT AT ALL.” Louis chose Lil over Henderson and moved back to Chicago.

Although his time with the great Henderson band lasted only a year, Armstrong had established himself as the most exciting horn player in the country.

Here’s one more for the road. I remember first hearing about the great tap dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson from a tribute dance Bojangles of Harlem that Fred Astaire did in his 1938 movie Swing Time:

As it turns out, Armstrong had seen Bojangles perform in Chicago in 1922. This inspired him with the idea that there was more to entertaining than just playing well. However, Oliver only allowed him to dance on occasion and sing only at out-of-town performances. Even Henderson was reluctant to allow him to sing. But he did allow him to speak at the end of the band’s 1924 recording of Everybody Lives My Baby:

This was the first time Armstrong’s voice was heard on a record.

From his source in New Orleans, up the Mississippi River with Fate Marable, to Chicago with King Oliver, and to New York City with Fletcher Henderson, like “The Father of Running Waters,” the music and legacy of Louis Armstrong just keeps rolling along…

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of Ethio-jazz.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel so inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Man to hear those early jazz songs on the riverboats back in the day must've been something special...

Thanks for the article Tyler, the only suggestion I would make is to locate, on YouTube, some much better transfers of the King Oliver band which have been made in recent years and give us a much radically clearer idea of what the band actually sounded like. I'm not where I can get to them but I'll try to search later.