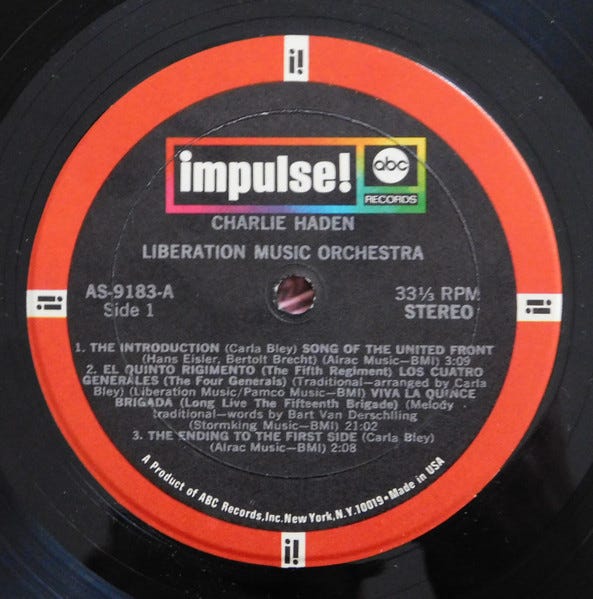

International politics and social concerns made a strong impact on Haden’s first album as a leader, Charlie Haden: Liberation Music Orchestra, recorded over three days in late April 1969. It was released on the Impulse! label in January 1970. The album was recorded by Charlie Haden, Carla Bley, and eleven other musicians in Judson Hall at 165 W. 57th Street, across from Carnegie Hall in New York City:

The recording sessions were particularly moving in that Haden invited survivors of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion in the New York City area. Of the approximately 3,015 United States Lincoln Battalion volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, 681 were killed in action or died of wounds or sickness. Haden recalled, “I called one of the men I knew, and he got in touch with everybody else, and they brought their wives.”

This is a seminal album in jazz history and a noble cause. From the very beginning, Haden wanted to make a strong political statement - even if he was the only musician who took it all to heart. Carla Bley, who was responsible for a large part of the album’s arrangement and songwriting, remembers, “I wanted to be a part of anything at all that was important and exciting and different. But none of the guys in the band shared Charlie’s political viewpoints. It was a gig.”

These days, protest albums are almost unheard of in jazz. Even in the 1960s, the decade of protests, there were few. In an August 2005 interview, Haden reflected on the album’s release, “The protest records back then were about race, and not about the administration waging war against other countries. There’s only a few people in all art forms, who place their concerns in what is going on - Picasso is a good example, about the Spanish Civil War.”

Haden was speaking about Picasso’s 1937 painting Guernica, a response to the April 26, 1937 massacre in Guernica, a Basque Country town in northern Spain, which was bombed by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy at the request of the Spanish Nationalists.

Haden continues, “The thing that concerned me in 1968, when I was sitting in a car outside a club I was playing and listening to the news, was that Nixon had just bombed Cambodia, and all these people were killed. The Democratic convention was going on in Chicago and all these people had been arrested, and so that’s when I started thinking about protest.”

Charlie Haden: Liberation Music Orchestra was based primarily on ideas he had several years earlier while listening to music he had collected from the Spanish Civil War, which took place from 1936 to 1939. The war was fought between: Republicans loyal to the left-leaning Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic, with various socialist, communist, separatist, anarchist, and republican parties; and the opposing Nationalists alliance of Falangists, monarchists, conservatives, and traditionalists led by General Francisco Franco’s military junta.

Over the years, the more I listen to this album, the more I like it. But once I actually pulled back the curtain of the music itself to understand the origins, I don’t think I ever really heard it.

I have not yet dedicated an entire journey to a single album, but I think this album deserves a deep dive.

Side 1:

The first track on side 1 combines The Introduction, written by Bley, with Song of the United Front, written in 1934 by Bertolt Brecht and Hanns Eisler. Incidentally, Eisler wrote the East German national anthem in 1949.

Song of the United Front was made famous by Ernst Busch, who in 1937 joined the International Brigades to fight against the Nationalists in Spain and broadcasted wartime songs on Radio Barcelona and Radio Madrid.

Here is a 1960s video of Ernst Busch singing Song of the United Front, with an appearance at the end by Hanns Eisler:

It is by no accident that Haden chose this song to open his album. It clearly states his passionate involvement with left-wing political and social concerns.

These first two tracks on side 1 have always reminded me of Willem Breuker’s music, not only the sound but the overt mixture of politics and jazz.

A significant and controversial moment took place in The Netherlands in October 1966, when Willem Breuker’s experimental piece Litany for the 14th of June, 1966 premiered at the Jazz Festival in Loosdrecht. The largely pre-composed performance consisted of an 18-piece orchestra playing against the backdrop of singer Sofia van Lier reciting newspaper reports on the suspicious death during riots of a protesting construction worker.

With its unconventional sound and social-political theme, the performance was unprecedented at a festival known for pigeonholing musicians into categories like Dixieland, modern jazz, or Hard Bop. This marked the first time a group of musicians/artists acted with a pronounced commitment to social and political engagement fundamental to their activities.

You can read more about Willem Breuker’s Litany for the 14th of June, 1966 here:

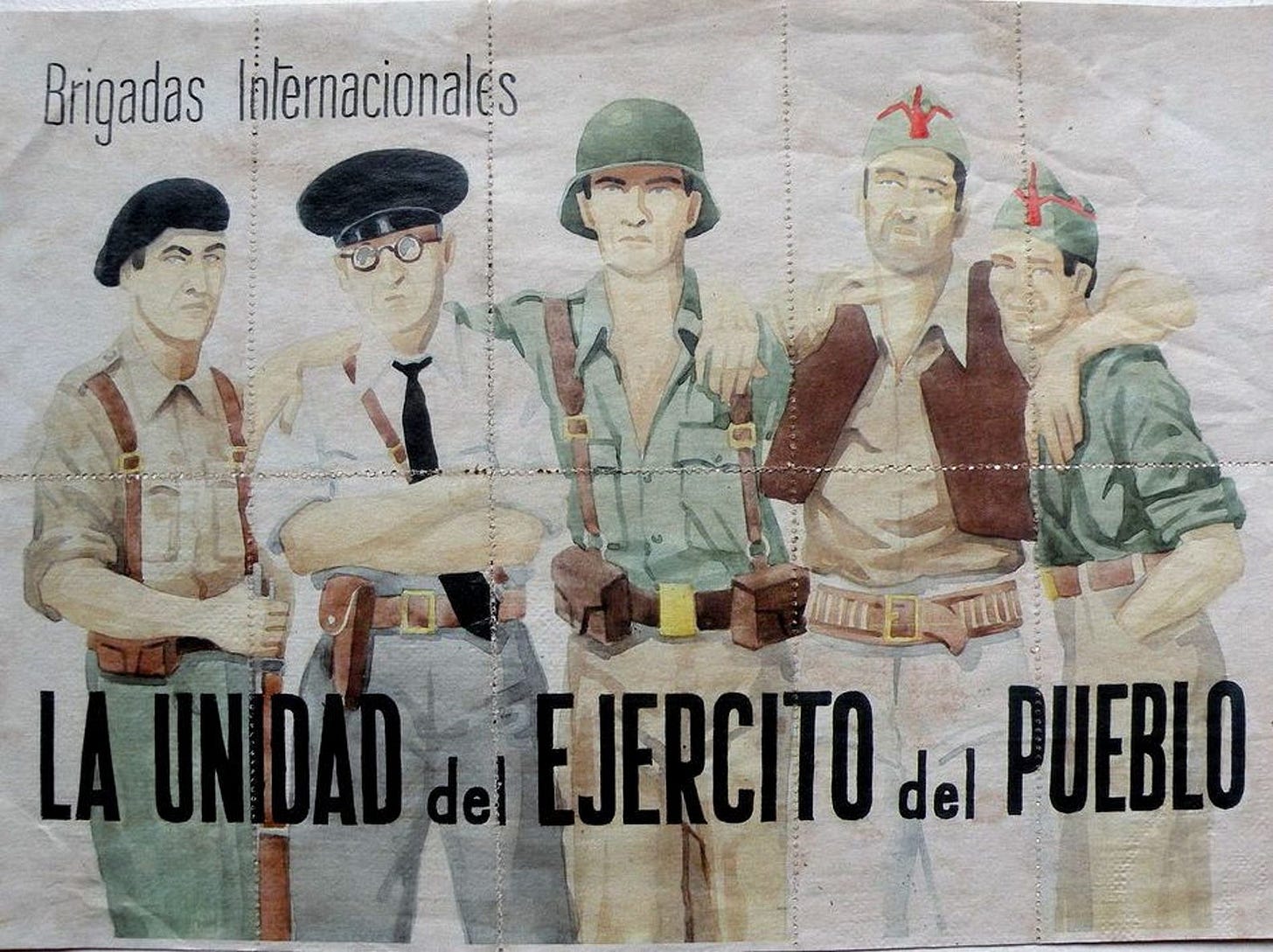

The second track, and really the core of the album, is a sweeping twenty-one-minute suite of three anthems from the Spanish Civil War: El quinto regimento; Los Cuatro Generales; and Viva La Quince Brigada. Rather than just play that suite, I’d like to play the songs that inspired Haden. I think it’s better to listen to and become familiar with these originals before listening to Haden and Bley’s version (you can listen to theirs here).

The first, El quinto regimiento, was the anthem of the elite Fifth Regiment loyal to the Spanish Republic. According to historian Eduardo Comín Colomer, in barely half a year the loyalist regiment had managed to become one of the most famous units of the whole conflict.[

The second, Los Quatros Generales, was the popular old Spanish tune, Los Cuatro Muleros (The Four Mule Drivers), that took on new words in the form of a hymn to the Madrileños (citizens of Madrid), who in November 1936 bravely withstood, for a while, the Fascists’ siege of their city, foiled the coup, and sparked a civil war. The four generals are usually identified as Francisco Franco, Queipo de Llano, José Sanjurjo, and Emilio Mola.

The third, Viva la Quince Brigada, is one of the most famous songs of the Spanish Republican troops during the Spanish Civil War. It was one of two anthems of the XV International Brigade, a mostly English-speaking tactical unit. The largest part of the Brigade was the American Lincoln Battalion.

International brigades were operated by the European and North American communist parties and made up of some 40,000 anti-fascist volunteers from all over the world.

Also known as Ay Carmela!, this was one of the Spanish Republican troop’s most popular songs during the Spanish Civil War:

The song is also known as El Paso del Ebro, remembering the 1938 Battle of the Ebro, the longest and largest battle of the Spanish Civil War, and the Republican’s last stand. Ernst Hemingway was one of the last British and American journalists to leave the battlefield, as the Republicans retreated back across the Ebro river in defeat.

Side 1 ends with Bley’s tongue-in-cheek, The Ending of the First Side.

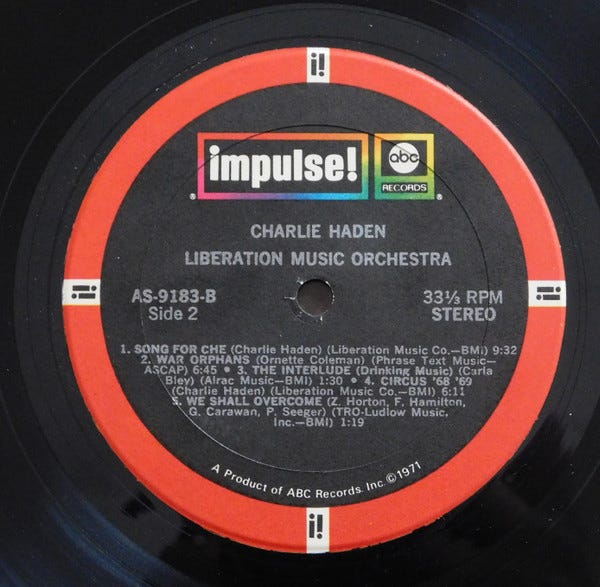

Side 2:

The first track on side 2 is the legendary Song for Che. Midway through the track, Haden samples Cuban Carlos Puebla singing a stanza from Hasta Siempre, a recording technique he would revisit in 1992 on his Quartet West albums:

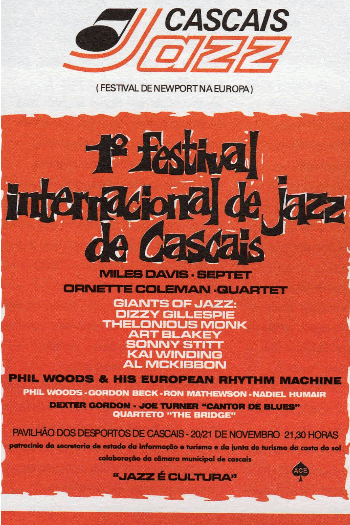

In 1971, during the Caetano administration (Marcelo Caetano was the Prime Minister of the authoritarian Estado Novo regime, later overthrown during the 1974 Carnation Revolution), Portugal hosted an important international jazz festival in Cascais - it was the first-ever jazz festival in that country.

Along with Ornette Coleman’s quartet, the festival featured the Miles Davis Septet and the Giants of Jazz, a quintet with Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and Art Blakey. Although the festival was state-sponsored, it became a space of political resistance for thousands and eventually led to Haden’s arrest.

At the time of the festival, Portugal had colonies in Guinea-Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique and was fighting nationalist movements in these regions. During the concert, when it was time for his Song for Che, Haden leaned down to his bass mic and dedicated the song to the Black peoples’ liberation movements in the colonies. Haden recalled, “…the young people there, students, that were in the cheap seats in front, and they all started cheering so loud that you couldn’t hear the music.”

Later the Portuguese secret police arrested, jailed, and interrogated him for hours, telling him, “Mr. Haden, you shouldn’t mix politics with music!” Fortunately, after a couple of days, Ornette Coleman intervened and Haden was released.

Here is an excellent video showing Haden’s return years later to the hockey arena in Cascais, Portugal where that festival was held. The video shows actual footage of Haden’s dedication at the beginning of the song. It concludes with Haden and Portuguese guitarist Carlos Paredes playing a live version of Song for Che:

The rest of the tracks on side 2 are interesting but mostly stand alone with no real ties to the Spanish Civil War, that I can tell anyway. The highlight of these for me is the Ornette Coleman song War Orphans:

The final track on this album, We Shall Overcome, sounds a lot more to me like it came from the First Act of Dave Burrell’s la vie de bohême than We Shall Overcome, but Burrell’s album was recorded on December 21, 1969 at Studio Saravah in Paris, after this recording was already completed.

Charlie Haden clearly did not listen when the Portuguese secret police told him not to mix politics with music. Over nearly a forty year period, Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra went on to release four more albums, all focusing on oppression and injustice in different parts of the world. Their final album was 2004’s Not in Our Name, which protested the US-led war in Iraq.

Activism was a big part of who Charlie Haden was, and the Liberation Music Orchestra was his way to represent the unheard voices of oppressed people everywhere. Haden explained, “People sometimes ask me if it made any difference to make a recording like this. What is important is that we chose to express our concerns when the circumstances warranted it out of our natural mode of expression which is music.”

Charlie Haden’s art was art with a social purpose, which is perhaps the highest form of art - for this, we are truly grateful.

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles in to explore the wild and turbulent waters of pianist Dave Burrell.

If you feel so inclined and would like to buy me a cup of coffee to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys, please hit this link. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button at the bottom of the page. Also, if you feel so inclined, become a subscriber to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button below.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey by Tyler King is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

thank you for opening my eyes to the Liberation Music Orchestra!! your research and threading the various musical pieces together is extraordinary! we're not worthy!!