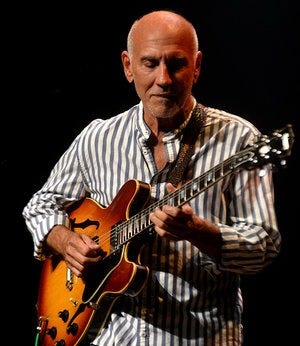

Sound, I guess. When I say sound, I mean the color - what color can I add to make it fun… but not make it so out that it’s not useable.

-Larry Carlton’s response to what he thinks about when improvising chord melodies

When I was a kid growing up in the 1970s, it was much harder to find music.

Most houses had radios, but then you were at the mercy of a DJ or whoever owned the radio, like your mom and dad, which never really worked well for me. The Bellaire Elementary School principal’s kid Jimmy Feil, who ran the warming house by the skating rink by the school, had a radio always tuned to the rock station KDWB - I still remember the station jingle, “KDWB 63”, which you can hear at the start of this video:

There was also the car radio, but once again, the driver controlled what we listened to and I didn’t drive.

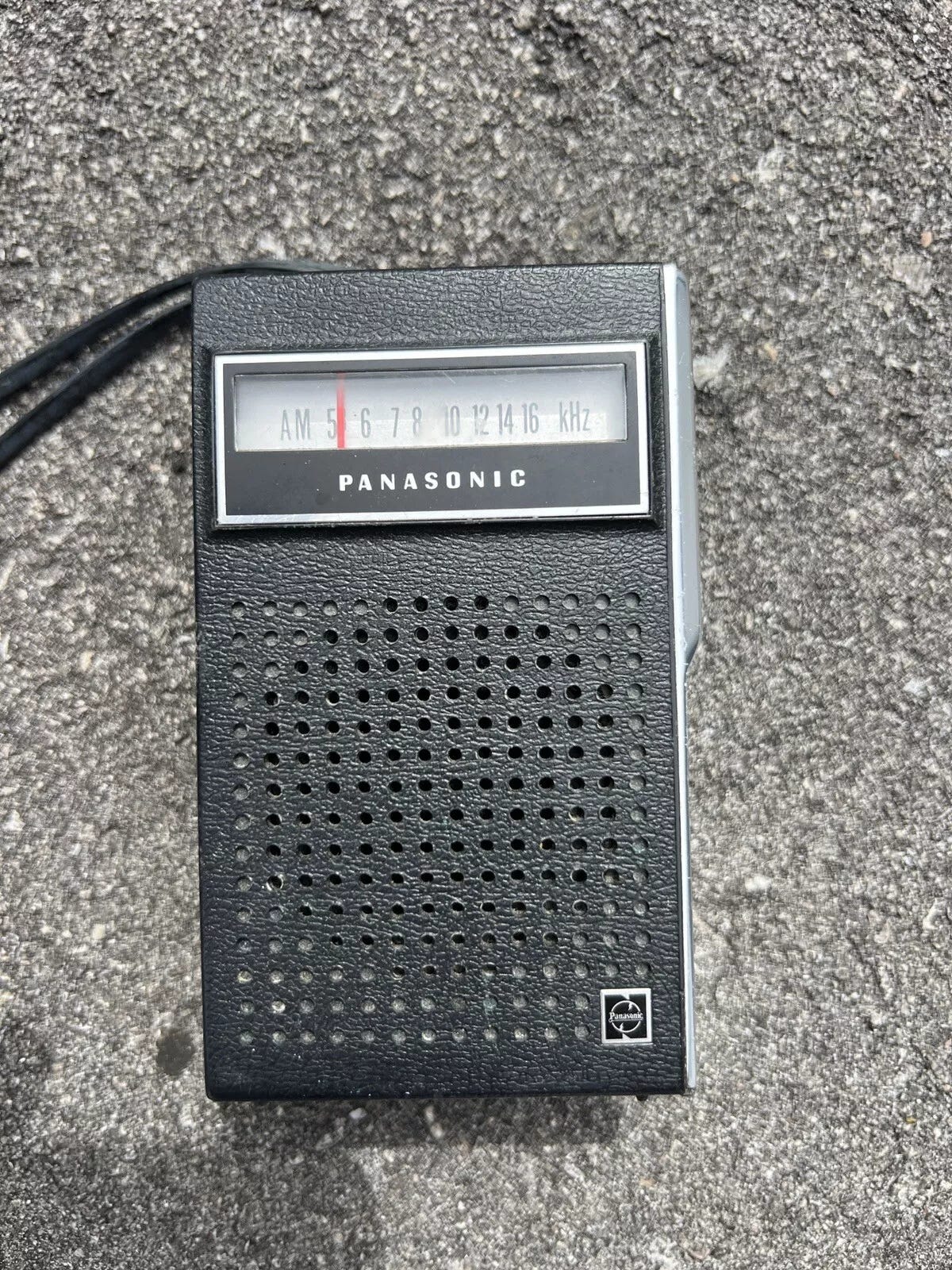

One day, I got a transistor radio. Finally, I could take the music mobile and, more importantly, listen to whatever music I wanted to by myself with no one around.

It looked something like this:

Back then, I was like the guy on Steely Dan’s Bad Sneakers:

Bad sneakers and piña colada, my friend

Stomping on the avenue by Radio City with a

Transistor and a large sum of money to spend

But I was wearing beat-up Converse All-Stars and a large sum of money was enough to buy as many Chunky or Clarke Bars as I wanted at the Red Owl up the street.

I remember hearing Hall & Oates's She’s Gone when it came out in 1973. It played a million times on the radio. I had no idea the saxophone solo was by Multi-instrumentalist Joe Farrell. I wrote about this last fall here:

In that leg of our journey, I mentioned how I thought Joe Farrell was perhaps the single jazz musician heard the most by everyone and known by almost no one. Larry Carlton is in that same position. In a 2019 interview with Carlton at The Baked Potato in Studio City, Los Angeles, Rick Beato said about Carlton when he introduced him, “You’ve heard him and not realized it on the radio for years and years.”

When I moved on to junior high school, records became more popular. Records were hard to find too. My sister had a little 45 rpm record player that was cool. She played some Motown records and other pop hits. She even had The Partridge Family star David Cassidy’s 1972 hit Cherish.

Many years later, when I started to care about who was playing on albums, I read that Larry Carlton was a session musician on Cassidy’s Cherish. The first time I heard his name would be over a decade later, in 1989 at the LA Forum.

In the 1980s while stationed in Germany, I befriended Water Trout while he was touring with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. When I returned to the States and lived in Carmel, California, I called Walter. He was living in Huntington Beach and invited me down for a big blues festival at the Forum.

He gave me an All-Access pass. After his show, I met him in the green room. So, there we were with John Mayall, Etta James, Eddie Cleanhead Vinson, and others. But Walter wanted to get out of there, so we went out to the backstage area. While we were talking, he stopped mid-sentence and said, “Listen. That’s Larry Carlton.” I listened for a few seconds, and he looked at me and said, “Man, I love his tone.” It was clear to me that he wanted to leave the green room to hear Larry Carlton play. From that point on, I’ve been following Larry Carlton’s amazing career. He has released a lot of fine albums as a leader, but the thing that amazes me the most about Carlton is his work in a supporting role. He is the ultimate tone poet.

This week on the Big River called Jazz we dig in our paddles to discover the world of Larry Carlton’s studio musician work.

Larry Carlton was born in Torrance, California on March 2, 1948. He started playing guitar at six years old. He played in bands in high school and then went to junior college at Long Beach State College while playing professionally at clubs in Los Angeles. He was influenced by Joe Pass, Barney Kessell, and Wes Montgomery.

During the 1970s, he found steady work as a studio musician on electric and acoustic guitar in a variety of genres from pop, jazz pop, rock, rhythm and blues, to soul and country. But if we were to go back to the first time I heard his tone poems without knowing who Larry Carlton was, it was in 1976 when I was in junior high school in White Bear Lake, Minnesota. That was the year I went to my first used record store - an obsession that came on slowly, then not slowly.

It was too far to walk to, so I bribed my brother or sister with allowance money to drive me to the record store. The deal was: “You drive. I pay for your record.” It worked every time. On one of those trips, I bought my first jazz album, which I’d heard on the smooth jazz radio station while doing homework. The album was John Klemmer’s Touch:

From that album, here is Sleeping Eyes:

I have always marveled at the wonderful open brush strokes behind Klemmer’s horn. It would be many years later before I realized it was Larry Carlton’s work.

On the more popular radio stations in 1976, you’d hear hit songs from Steely Dan’s fourth studio release Katy Lied, like Doctor Wu and Bad Sneakers. Another song on the album with a more blues feel is Daddy Don’t Live in that New York City No More. This was the first track Steely Dan featured Carlton on lead guitar:

The following year Steely Dan put out The Royal Scam, which has Carlton’s now-famous Kid Charlemagne solo. I prefer his work on Don’t Take Me Alive. He’s still a tone poet, but this poem is less ethereal and from that first marvelous chord more in your face:

Interestingly, John Klemmer plays tenor saxophone on The Caves of Altamira from this album.

At the same time Carlton was recording with Steely Dan he was also a part of the jazz fusion group The Crusaders, who Joni Mitchell invited to play on her 1975 album The Hissing of Summer Lawns.

On the album’s Don’t Interrupt the Sorrow Carlton’s tone is like a shooting star moving across the sky, filling in the wonderful spaces of Mitchell’s composition:

Carlton’s playing has a restrained, almost meditative, elegance to it on his tracks with Mitchell that hooked me right away. Incidentally, that’s Robben Ford on Dobro - that makes two of my favorite guitar players on one song.

Carlton was invited to play on Mitchell’s next album, Hejira. This album has two of my favorite Carlton contributions. The first is A Strange Boy, where his tone is full of strange, sweet chords like long brush strokes painted across a canvas:

The second is Blue Motel Room, with Carlton playing acoustic guitar. Electric or acoustic, it doesn’t matter. Carlton’s tone makes everything sound just right, down to earth, and dreamy and finds a way to my heart:

I’ve always been struck by the title of this album - “Hejira”. I always found it a strange title until I looked up its meaning. One definition I found is “a journey especially when undertaken to escape from a dangerous or undesirable situation.” Then it made sense. In both songs, Carlton captures that sense of wanderlust and the melancholy that can ride with it. His tone fills in the wonderful spaces in Mitchell’s songs like six jet planes leaving six white vapor trails across the bleak terrain…

Here’s one more for the road. Getting back to where we started - I didn’t know it back then, but naturally, as part of Tom Scott’s L.A. Express at the time, Larry Carlton played on Joni Mitchell’s classic hit Help Me:

Of course, I heard this song a million times on my transistor while walking in my bad sneakers up to the Red Owl to buy some candy bars. As I made my way through the woods, his guitar licks felt like freedom - they just made me feel good.

I found out many years later that on April 6, 1988, Larry Carlton was shot in the neck by a young man on a bicycle passing his North Hollywood studio. He was lucky to survive. The bullet passed through his jugular vein. The doctors said he could have died instantly but he survived - it was a miracle. The bullet also severed the main nerve to his larynx and paralyzed his left vocal cord. It took more than six months before he could play again. So, when I saw him at the LA Forum in 1989, he had already recovered and was just getting back on the scene. However, according to many, his playing better than ever. When asked about this in a March 2012 interview, he replied:

Carlton: “Yeah… I had people tell me that I was a different player after the shooting. I didn’t know it, but they said it sounded different.”

Interviewer: “‘Different’ in terms of technique or feeling?”

Carlton: “In terms of feeling.”

Carlton went on to say that great musicians play from the heart, not from the head. He admits that he is not the greatest technician, that’s just not his thing. He prefers to play by feel, and I think it’s through this philosophy that he finds freedom. That’s what makes Larry Carlton the ultimate tone poet.

In a June 1989 interview shortly after his recovery, he said, “If I’m fortunate enough, my dream would be to continue to make my music and just grow old with my audience.” Well, it looks like you’ve done it. Larry Carlton is still touring, and I saw him play at the Dakota in Minneapolis on September 5, 2024.

Thanks for all the great music, Larry!

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of Russian and American ballet choreographer George Balanchine.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel so inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….