Never the world's most highly animated showman or greatest stage personality, but a tone so beautiful it sometimes brought tears to the eyes—this was Johnny Hodges. This is Johnny Hodges. Our band will never sound the same.

-Duke Ellington

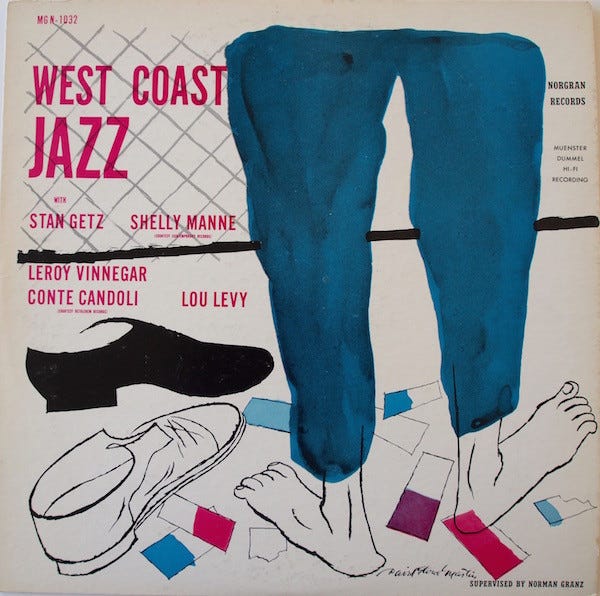

From the start of my jazz journey, I was attracted to albums by their cover art - often either buying or passing on albums strictly on the quality of the art. I equated a cool album cover with good music, and I always looked forward to judging if the quality of the music measured up to the quality of the art. My theory was that even if the music didn’t measure up at least I’d have a cool album cover.

This practice in some odd way served me well, and David Stone Martin always had some of the best album cover art. You can read more about him here:

Here’s one of my favorite David Stone Martin covers with that distinctive signature at the bottom right next to the left heel:

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, I picked up a lot of cool David Stone Martin covers at Logos Books and Records in Santa Cruz. I lived in Cupertino and drove over Highway 17 every Saturday morning to get there when it opened. I’d be first at the new arrivals and there would always be a batch of five or so jazz classics to pick from - they knew I was coming…

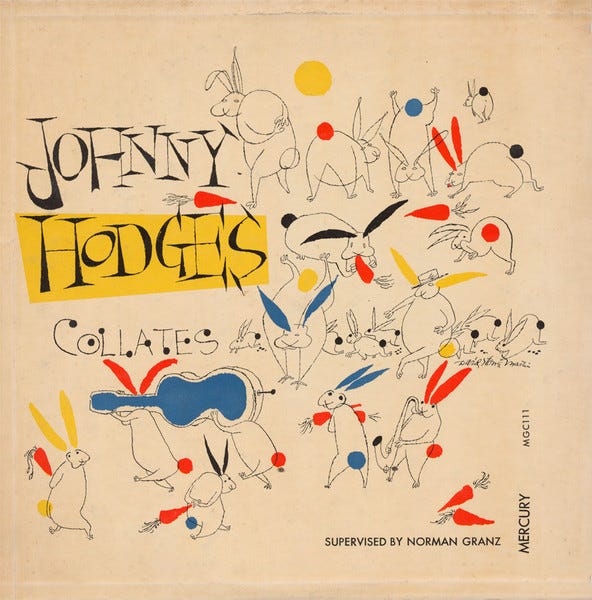

One morning I found this 10” record, Johnny Hodges Collates. It was on this record that I heard the great saxophonist Johnny Hodges for the first - before I ever knew he played in Duke Ellington’s band:

This is the 1954 re-issue of some small group recordings that included one of his big hits Castle Rock:

Castle Rock was recorded in 1951 and originally released by Mercury Records on 78rpm:

Hodges had just shocked the world by leaving Duke Ellington’s orchestra, taking with him some of Ellington’s stars like Sonny Greer, Al Sears, and Lawrence Brown. However, these were not Hodges’ first small group recordings.

This week on that Big River called Jazz we’ll dig in our paddles and explore the world of Johnny Hodges’ earliest small group recordings.

After spending time taking lessons with Sidney Bechet and later working with him at his Club Bechet in New York, Johnny Hodges joined Duke Ellington’s Orchestra in 1928. His first recording with Ellington was Yellow Dog Blues, recorded for Brunswick in June 1928:

As was the trend at the time, Hodges also recorded with musicians outside of Ellington’s band and in 1935 played on some legendary records with Billie Holiday and Teddy Wilson. Here’s I Cried For You with Johnny Hodges on alto:

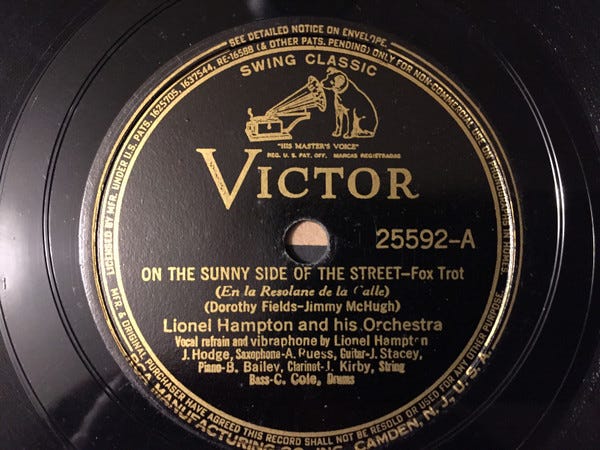

Then again in 1937, Hodges recorded the classic On the Sunny Side of the Street with Lionel Hampton and his Orchestra:

Hodges plays such a wonderful solo and dig Hampton’s vocals:

In 1937 in New York City Hodges recorded his debut session as a leader on the Vocalion label. Then again he led sessions in early 1938, which included Jeep’s Blues, featured above at the beginning of this week’s journey:

By 1940, on the strength of small group sessions like these, Ellington’s sidemen grew in stature alongside their leader, and Johnny Hodges was now universally known as one of the greatest jazz saxophonists, an unquestionable peer of Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, and Lester Young.

After over a decade of playing in Harlem, In January 1941, Ellington took his orchestra west. Soon after arriving in LA, they got a seven-week gig at the Casa Mañana, a popular nightclub near the MGM studios. Hollywood gagman Sid Kuller heard Duke’s band at the club and invited him to his place in the Hollywood Hills, where he kept an open house for jazz and swing bands to regularly jam.

One night while working on the Marx Brothers’ The Big Store, Kuller came home late from the studio and said, “Hey, this joint sure is jumpin’!” Ellington replied, “Jumpin’ for joy.” Kuller suggested that they collaborate on a stage production with an all-black revue that challenged segregation and old Uncle Tom stereotypes still prevalent in the industry. They’d call the show Jump For Joy.

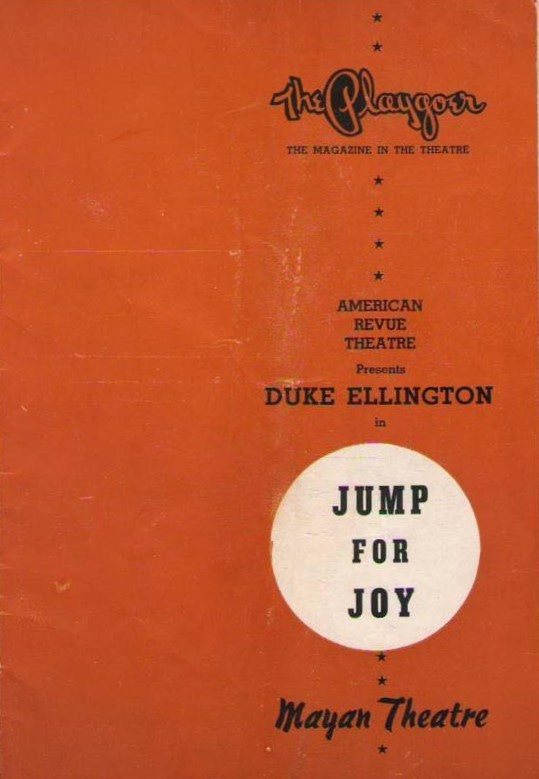

Jump for Joy opened at the Mayan Theater on July 10, 1941, and ran for 122 performances until September 29, 1941:

On July 3, 1941, just a week before opening night, Johnny Hodges recorded a small group session in Hollywood that resulted in two of my favorite jazz classics. The first is a Billy Strayhorn arrangement of the Hodges composition Squatty Roo, another of Hodges’ nicknames. For this track, Hodges was joined by Duke Ellington on piano, Harry Carney on Trombone, Jimmy Blanton on bass, and Sonny Greer on drums:

The second is Going Out The Back Way and just marvel at Blanton’s bass playing:

Blanton is the real star on this track. However, once Jump For Joy premiered Blanton was showing symptoms of tuberculosis. His condition progressively worsened throughout the show's run at the Mayan Theatre. He completed the run of Jump For Joy but in November was forced to leave the band to seek full-time medical care. The band left Los Angeles in December 1941, leaving Blanton behind to await his fate. He was replaced by San Francisco bassist Alvin “Junior” Raglin.

Jimmy Blanton died on July 30, 1942, at a sanatorium in Duarte, California. He was only 23 years old. I wrote about Jimmy Blanton back in 2021:

Here’s one (actually two) more for the road. In 1951 after 22 years with Duke, Hodges broke away to form his own group that would later include a young John Coltrane, who took Hodges’ style and expanded it on tenor. In 1954, Coltrane recorded this classic version of On the Sunny Side of the Street with Hodges’ group on the Norgran label:

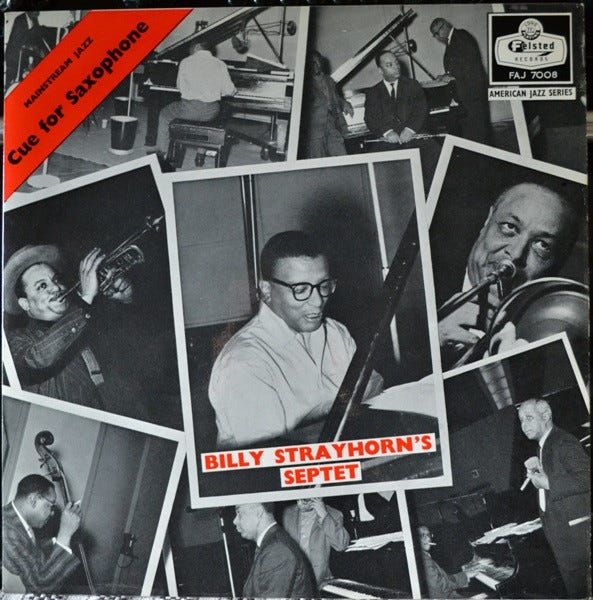

During 1958 and 1959, British producer Stanley Dance supervised albums in New York for the Felsted label, a subsidiary of Decca Records. One of the albums he produced was Cue for Saxophone by pianist and composer Billy Strayhorn's Septet with members of the Duke Ellington Orchestra:

The session was recorded in New York City on April 14, 1959. It was more of a Johnny Hodges small-group jazz album, much like the Hodges LPs released by Verve Records at the time. However, for contractual reasons, it was released under Strayhorn's name with Hodges listed under the pseudonym "Cue Porter." Incidentally, Cue was also the name of his wife - Edith Cue Fitzgerald, a dancer in the Cotton Club chorus.

Here’s the full album. If you go to the 20:16 minute mark, you can listen to Hodges and Strayhorn’s classic bluesy composition Watch Your Cue:

Johnny Hodges was one of jazz’s greatest solo instrumentalists and without question one of the three most important alto saxophonists in music history. However, just as his music was something to emulate, so was his style. Blending loose suits with a Bohemian flair, he always looked debonair. Like those David Stone Martin album covers, Hodges taught me that style matters!

Next week, on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles in and explore the world of John Cage and Merce Cunningham.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Wonderful

Johnny Hodges made his debut as a leader in 1937, not 1938. Ref. https://ellingtonia.com/discography/1931-1940/