The aim of teaching is usually to show people how to do something. What [English drummer, John] Stevens aims at, it seems to me, is to instill in the people he works with enough confidence to try and attempt what they want to do before they know how to do it.

-Derek Bailey

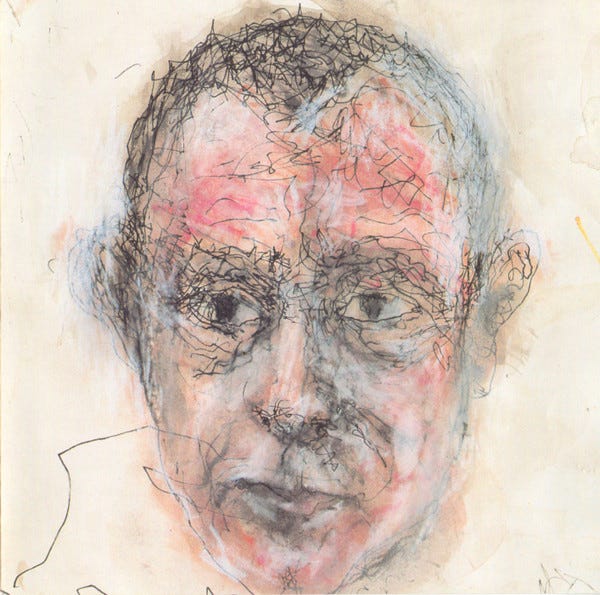

While browsing at Chicago’s Jazz Record Mart in the early 2000s, I first ran across the name John Stevens on the cover of this Nessa Records release:

Back then, the Spontaneous Music Ensemble reference at the bottom didn’t register as anything more than a description of the music. I bought the album on the Nessa label’s stellar reputation alone, as I had heard of neither Bobby Bradford nor John Stevens.

I wrote about Nessa Records here:

The album was recorded at Polydor Studios in London on July 9, 1971, and released on the Freedom label in 1974. However, the complete document of that session didn't appear until the early 1980s when Nessa released it as volumes 1 & 2.

According to Chuck Nessa, when Michael Cuscuna moved to Arista and began the Freedom series, Nessa asked if he intended to reissue the Bobby Bradford with John Stevens record. Cuscuna said he was passing on it. However, he said that Alan Bates (founder of Black Lion and Freedom Records) owed him for work done, and maybe he could arrange to transfer the masters to him to cover the debt. Bates agreed. It was then discovered there was enough material for a second record and the masters became Nessa’s, who reprogrammed the material and released two LPs. Nessa later combined them to make a CD. You can find that CD here.

Over the years, I’d learn more about the American Bobby Bradford; however, John Stevens would fade from my memory.

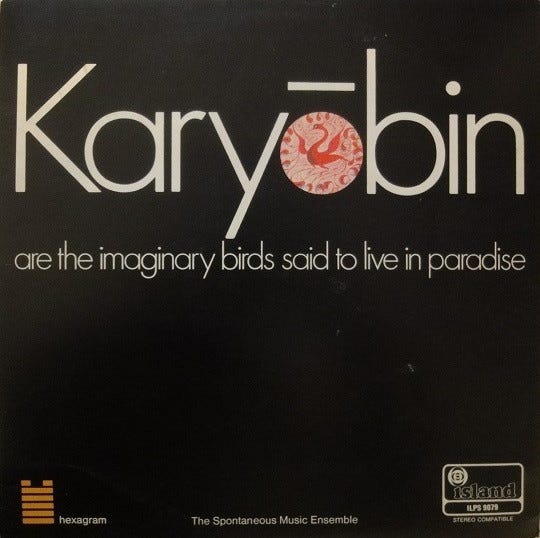

Then, about a decade later, I read about an album called Karyōbin by a group called Spontaneous Music Ensemble:

The drummer for the Spontaneous Music Ensemble was John Stevens - there was that name again.

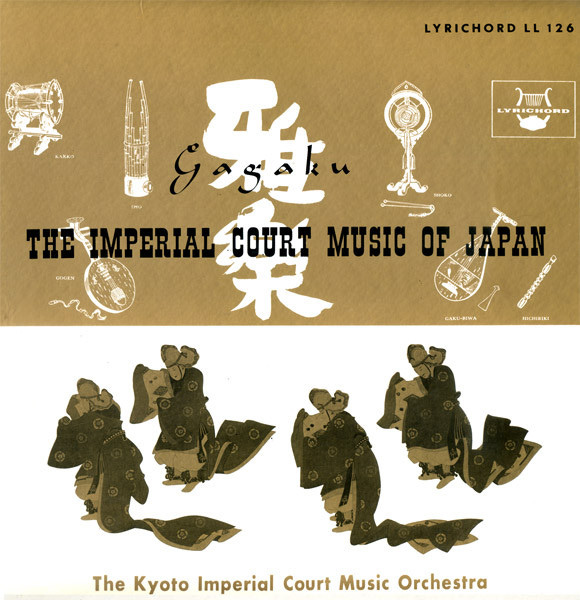

Karyōbin was recorded in London on February 18, 1968, and got its name from a song Stevens heard on a 1964 album he found called: Gagaku: Imperial Court Music of Japan:

From the album, here is Etenraku:

Gagaku is considered one of the world’s oldest continuously performed music traditions. It was developed as court music of the Kyoto Imperial Palace. Gagaku music influenced many Western musicians including La Monte Young’s numerous works of drone music, especially his 1958 Trio for Strings and Olivier Messiaen’s 1962 Sept haï-kaïs. Gagaku also had an important impact on John Stevens, who with saxophonist Trevor Watts in 1965 founded the Spontaneous Music Ensemble (SME).

I find it alarming that the SME’s Karyōbin, widely considered to be a founding document of British free improvisation music, has been available only sporadically since 1968, when it was released on Island Records, with guitarist Derek Bailey’s name misprinted on the cover as Dennis Bailey no less.

SME’s brainchild was drummer John Stevens, and he remained the one constant throughout the ensemble’s long history.

This week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig in our paddles and explore the world of John Stevens.

John Stevens was born in Brentford, Middlesex, England, the son of a tap dancer. He listened to jazz as a child but was more interested in drawing and painting, through which he expressed himself throughout his life. He studied at the Ealing Art College and then started work in a design studio, but left at 19 years old to join the Royal Air Force. He studied the drums at the Royal Air Force School of Music in Uxbridge, and while there met Trevor Watts and Paul Rutherford, with whom in 1966 he formed the Spontaneous Music Ensemble.

The SME began an intensive six nights per week residency at London’s Little Theatre Club in January 1966 and recorded their first album Challenge on the small Eyemark label the following month.

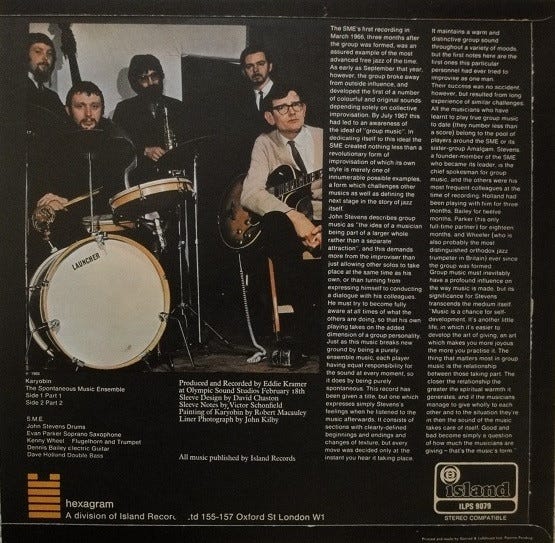

By the summer of 1967, SME consisted of Stevens and saxophonist Evan Parker. However, when an offer came for SME to make an LP for Island Records, they saw it as a perfect opportunity to invite trumpeter Kenny Wheeler, Derek Bailey, and bassist Dave Holland to join them in a quintet. From the album’s back cover, here’s the group:

Stevens forged a musical concept midway between American free jazz and the non-idiomatic improvising ensemble of British group AMM that freely improvised at a very high degree, but retained something of the "jazz sound." SME was less concerned with abstractions, but rather with shapes, relationships, and the organic growth of musical conversation. There are no solos in SME music. The group focused on an extremely open, leaderless approach, where a premium was placed on careful and considered listening by all musicians.

Saxophonist Evan Parker observed that Stevens had two basic rules: “(1) If you can't hear another musician, you're playing too loud, and (2) if the music you're producing doesn't regularly relate to what you're hearing others create, why be in the group?”

After Karyōbin, in 1969 SME recorded a self-titled album on Polydor label, and in 1970 they recorded For You to Share, released on A Records, a short-lived UK mostly jazz label formed in 1972 by Trevor Watts and John Stevens. The album wasn’t released until 1973.

In July 1971, at Hérouville-Saint-Clair in France, they recorded Birds of a Feather, released in 1972 by BYG Records. Here is that album:

The first track is a fitting tribute to Albert Ayler.

By 1971, SME was all the rage, headlining at the three-day Palermo Pop 71 festival alongside the Jimmy Smith trio and Black Sabbath:

Here’s an important video of SME recorded in 1971 at the NRK Studio in Norway with Stevens’ nice introduction to what will be played:

British record producer Martin Davidson, without whom the British improv scene may have been unthinkable, said:

I came to terms with [free improvisation] in 1971. I had heard it starting in the mid-1960s, but could not relate to it. A 1971 concert by the Spontaneous Music Ensemble (with John Stevens, Trevor Watts, Julie Tippetts and Ron Herman) turned me on.

This edition of the SME kick-started Davidson’s formation in 1974 of Emanem Records to publish music too good and too adventurous to be considered by most other labels. One of Emanem’s first releases was a SME duo album with Stevens and Trevor Watts called Face To Face, recorded at London’s Little Theatre Club in December 1973 and released in 1975. Here’s a short piece from that album:

In the mid-1980s, Stevens and Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts hung out together and listened to jazz albums. Stevens helped Watts find the personnel and pick the tunes for his album Charlie Watts Jazz Orchestra Live At Fulham Town Hall, released by CBS in 1986. The band included British saxophonist Courtney Pine’s debut and echoed the days of Woody Herman's Herd.

Throughout the 1990s, Stevens continued to record outside SME. For example, in January 1993 at Watershed Studios in London, he recorded Bird In Widness, a session with British saxophonist Dick Heckstall-Smith. The album was released in 1995 on the German Konnex Records label, and Stevens supplied the album’s cover art. From the album, here is In & Out:

I first heard Heckstall-Smith way back in the 1970s on this early John Mayall album that I ran across in my brother’s record collection:

In 1967, Heckstall-Smith became a member of John Mayall's Bluesbreakers.

Bird In Widness was released posthumously, as John Stevens passed to the Western Lands on September 13, 1994. Heckstall-Smith dedicated the CD to Stevens and wrote: “John, oh John, my brother, you are still here.”

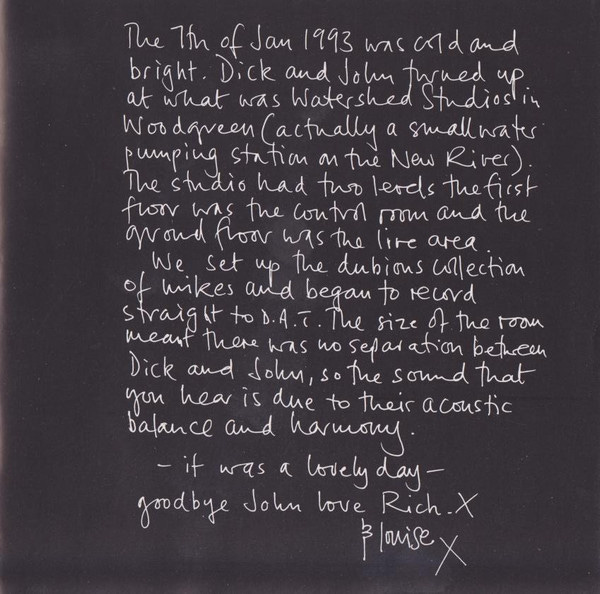

There is also a nice note to their father from Stevens’ two children Louise and Richie, who also recorded the album:

Here’s one more for the road. On this side of the pond, in America, British singer-songwriter and guitarist John Martyn is seldom if at all mentioned. However, in the UK, he is widely known and admired, which is a kin to the strange phenomenon that makes the Canadian band Tragically Hip cultishly revered in their homeland, but only narrowly known and less admired across the border in America. Anyway, filled with half-British blood, I like Martyn’s music.

In 1975, Martyn recorded the classic album Live At Leeds, originally only available by mail order from Martyn himself and often signed on the back cover with a dedication or message to the purchaser by John or John and his wife Beverley.

Although uncredited on the album, John Stevens joined Martyn and bassist Danny Thompson on a few tunes.

Martyn began his career at age 17 as a key member of the Scottish folk music scene, drawing inspiration from American blues and English traditional music. In 1967, he signed to Chris Blackwell's Island Records and the same year released his first album, London Conversation. By the 1970s, he was incorporating jazz and rock into his sound.

John Stevens was more than just a drummer. He was also a community organizer, dedicated to helping others in the musical community. In 1983, with Dave O’Donnell, Stevens started Community Music, a London-based network of music classes, workshops, and performing arts groups set up to encourage youths to join in making music. At a time when there were no community projects, Community Music broke down barriers and empowered young people to pursue their musical dreams - incidentally, Courtney Pine attended Community Music.

John Stevens’ death brought an end to the SME, one of the finest free collectives in the world; however, Stevens’ legacy continues!

John, oh John, you are still here. We are still listening…

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of the Trevor Watts.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

I tend to think free improvisation has run its course, and Birds of a Feather from 1971 confirms my impression. Nothing in that realm being played today comes close to the careful beauty of that group improv; what current musicians fail to achieve is the sense of newness and discovery of that first/second generation of free players.

John Martyn's best album is Solid Air, at least in my view. He was quite a difficult person. A phenomenal player though.

I saw SME in the early '70s in Edinburgh. Dudu Pukwana on pocket trumpet. I didn't understand it all and left at half time. I think I'd get it now having done some free playing myself.