Of course, he’s not a composer, but he’s an inventor - of genius.

-Arnold Schoenberg on John Cage

When the war came along, I decided to use only quiet sounds. There seemed to be no truth, no good, in anything big in society. But quiet sounds were like loneliness, or love, or friendship.

-John Cage

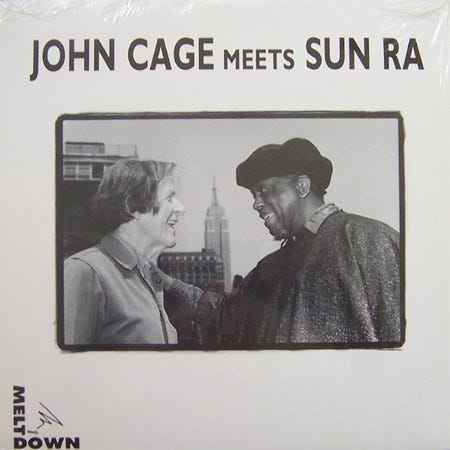

The first time I heard of John Cage was from this Sun Ra album:

In 1986, two of the twentieth century’s most important avant garde musicians and musical philosophers met and recorded a concert in of all places the Sideshows By the Seashore in Coney Island. At the time, I knew nothing of Cage and dismissed him entirely. Cage would remain in the shadows of my journey until 2008 when an amazing event happened in a granite quarry in central Minnesota.

I moved to Minnesota from Chicago in 2000. With my background in dance, I was aware of Merce Cunningham and the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. In 2005 the dance company had a residency at the Benedicta Arts Center at the College of St. Benedict in St. Joseph, Minnesota about an hour north of where I live. So when I heard that Cunningham’s epic Ocean would be performed in dramatic Rainbow Granite Quarry in Waite Park, near St. Cloud, Minnesota, I was first stunned and then excited.

As the sun set on a September day in 2008, a once-in-a-lifetime production of Merce Cunningham and John Cage’s monumental Ocean took place 150 feet below the earth’s surface in a massive granite quarry. It was magical - an event that scars you for life.

This week on that Big River called Jazz we dig in our paddles to discover the world of John Cage and Merce Cunningham, one of the richest creative partnerships in post-war art.

In a July 1997 issue of The Wire magazine, Louise Gray wrote:

John Cage exerted a profound influence on the course of modern music, yet his ideas and writings are often held to be more interesting than the sound of his own music.

I’ll add that when a composer’s most famous work is 4 minutes and 33 seconds of silence, that probably tells you something. However, as the title of Cage’s silent work 4’33” reveals, there’s much more to his music than meets the ears. It premiered in 1952 and, depending on your stance, is either the biggest statement of musical liberation and conceptual art ever or the biggest con ever.

Gray went on to write:

Cage’s music has often been described as head music rather than ear music, meaning it’s easier to think about than listen to. But maybe 4’33” is best described as heart music. Built on the concept that nothing is ever repeatable, its deepest foundations, far away from Cage’s manifest humour, are of sadness and melancholy.

Although strange, the title 4’33” is not arbitrary, as four minutes and 33 seconds equals 273 seconds, and minus 273 degrees Fahrenheit is absolute zero - the state at which all matter ceases to exist. This type of obfuscation defines Cage’s work, which began in earnest in San Francisco in 1938 when he met Bonnie Bird, head of the dance department at the Cornish School of the Art in Seattle.

Before joining the Cornish School, Bird had been a member of the original Martha Graham Dance Company. She offered Cage a job as her composer-accompanist, and he moved up to Seattle. After settling in, he organized a percussion orchestra.

While at the Cornish School, Cage met Merce Cunningham, who had joined his percussion orchestra. However, by 1939, Cunningham was asked by Martha Graham to join her dance company in New York. He moved to New York in September and danced his first role in December. It would be another four years before Cage and Cunningham’s paths would cross again.

In March 1940, Syvilla Fort, a local dancer and Cornish School graduate was booked to perform her solo Bacchanale but had no music. Since Cage was the only composer available, she called on him for the music. However, the Cornish Theater’s stage was only large enough for a grand piano, not the percussion ensemble he’d worked with. Therefore, Cage went about experimenting with ways to change and enhance the sound of the piano. In the end, he settled on a piano treated with a small bolt, a screw with nuts, and fibrous weather-stripping:

He called his invention the “prepared” piano and was, therefore, able to install in a different state a percussion orchestra in the small Cornish Theater. Here’s what Bacchanale sounded like:

This is a strange sound that seems to me like an amped-up cross between a Japanese koto like this:

…and an Appalachian frailing banjo - something like this:

Nonetheless, I like it.

In the summer of 1941, Cage moved to Chicago to teach a class in experimental music at the Chicago School of Design. The School was very much a transplant of Bauhaus artists, and Cage found himself in the company of other faculty like Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Mies van der Rohe, and Josef Albers. Cage met Max Ernst while he was visiting Chicago. Ernst issued an open invitation for Cage to stay in New York City in the apartment he shared with Peggy Guggenheim, who was planning to open her gallery Art of the Century. They proposed that Cage direct a percussion music concert to celebrate the gallery’s opening. So in the spring of 1942, he left for New York City. When we got there, he met up with Cunningham and started working on a series of choreographed solos, beginning with the groundbreaking Credo in US.

In a 2006 interview with The Wire magazine, Cunningham recalls Credo in US:

We decided that I would create a solo and Cage would make music, and we agreed on a particular rhythmic structure. He would go away and compose the music, and I’d compose the dance, and then we’d put the two together. So, with the rhythmic structure we would meet, so to speak, at structural points throughout the piece. But in between, the relationship was, for me, very difficult because I was accustomed to dancing to the music. I remember there was a point in the dance where I did a very strong movement, and there was no music at all. The next minute, the next second really, the piano suddenly made this large sound. I suddenly realised that dance had to be what it was on its own strength, without the sound supporting it. I suddenly realised what was possible.

This is an amazing concept and perhaps for the first time dance and music were placed on equal footing - dance no longer dependent on the music.

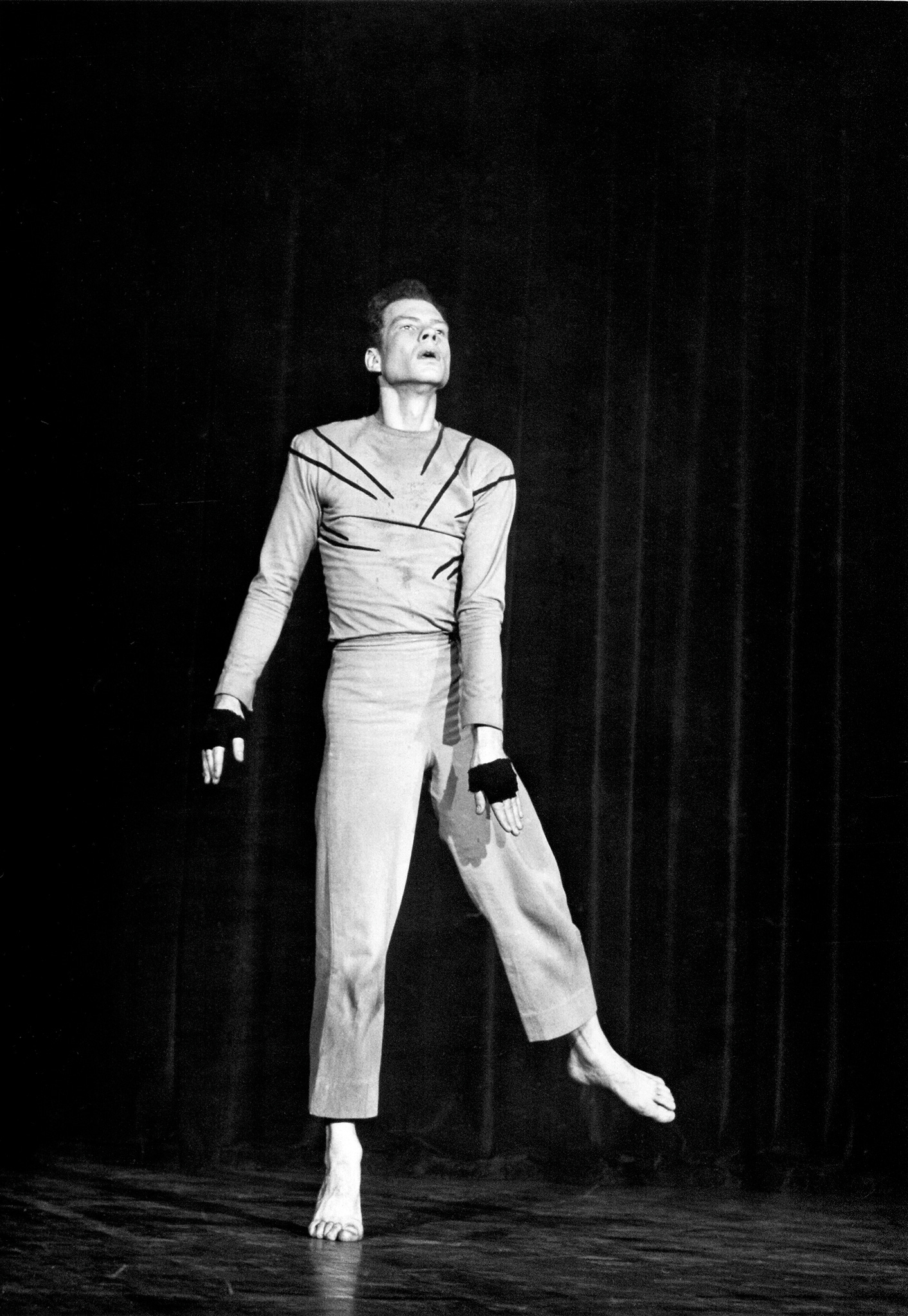

Two years into his partnership with Cage in New York City, in 1944 Cunningham performed his first solo concert at the Humphry-Weidman Studio Theatre. He danced to Cage’s composition Root of an Unfocus. This was another experiment in their idea that the music and the dance could be independent of each other, only coming together at structural points as defined by units of time rather than melody. Here’s Cunningham performing Root of an Unfocus:

In 1953 Cunningham founded the Merce Cunningham Dance Company at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where he and Cage had been spending summers.

It was at Black Mountain in 1953 that Cunningham premiered Untitled Solo with music by Christian Wolff. Untitled Solo was Cunningham’s first use of the ritual of tossing a coin to determine, through chance, the outline for a sequence of movements to find unexpected, fresh results. In his book with Jacqueline Lesschaeve The Dancer and the Dance, Cunningham explained:

[Using chance methods] I also began to see that there were all kinds of things that we thought we couldn’t do, and it was obviously not true… If you try it, a lot of time you can do it, and even if you can’t, it shows you something you didn’t know before.

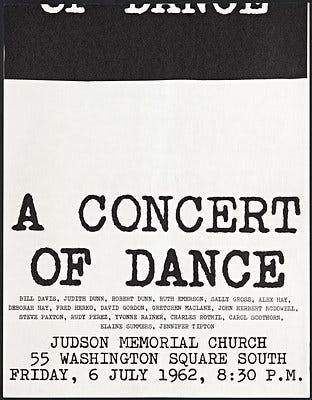

One of the things that I feel was important about Cage and Cunningham was how they inspired artists to find new ways of expression. For example, the Judson Dance Theater originated in 1962 from classes taught by Robert Dunn at the Merce Cunningham studio. Dunn was a musician studying experimental music theory with Cage. In Democracy’s Body, Judson Dance Theater, 1962 - 1964, Sally Banes wrote:

John Cage asked Robert Dunn to teach a class in choreography at Merce Cunningham studio in the fall of 1960. Dunn had taken Cage’s class in Composition of Experimental Music, taught at the New School for Social Research from 1959 to 1960, as had writers Jackson MacLow and Dick Higgins, the composers Toshi Ichiyanagi, and Al Hansen, George Brecht, and Allan Kaprow, all of whom were later associated with Happenings and Events.

Dunn eventually asked the head of the Judson Church on Washington Square in Greenwich Village if he could use the church as a venue for dance productions:

The church later became a jazz venue hosting Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman, and Noah Howard. We’ll get into that deeper a little further down the river…

A Concert of Dance was the first performance by the Judson Dance Theater, which took place on July 6, 1962. The concert featured works by 14 choreographers, including Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, David Gordon, Alex and Deborah Hay, Fred Herko, Elaine Summers, William Davis, and Ruth Emerson. The performers included students from Robert Dunn's composition class, Merce Cunningham Dance Company members, and other visual artists, filmmakers, and composers. Here’s the flyer from that first performance:

Almost twenty years later, in the spring of 1981, Merce Cunningham and composer John Cage began a residency at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. While here, they sat down to discuss their work and artistic process:

This brings us back to Merce Cunningham and John Cage’s monumental Ocean, which premiered during the Kunsten Festival des Arts at the Cirque Royal in Brussels on May 18, 1994, less than two years after Cage’s death.

Ocean represents both a culmination of previous events and an anticipation of things to come. According to Cunningham:

John was greatly concerned with James Joyce’s work and Joseph Campbell said that the next work Joyce might do would be about water. So John and I came up with this possibility. Musically and dance-wise, Ocean has 19 sections. This also comes from Joyce, who once said Ulysses had 17 sections and Finnegan’s Wake 18. So this one has 19. John wanted something in the round, and I agreed. The dancers, say, are here and the audience is around them. Then the music’s outside them, the audience submerged between the music and the dancers. It’s like a bath.

Cunningham’s 19 sections were choreographed using a chance process based on the number of hexagrams in the I Ching - 64, but due to the length of the dance, it was doubled to 128. A revival of Ocean was held on July 12, 2005, at Lincoln Center in New York City, and then on September 11-13, 2008, the Walker Art Center restaged Ocean on the floor of this quarry:

Here’s an amazing, short must-see video describing the event:

Ocean is Cunningham’s most ambitious work, rarely performed due to its scale. It featured his 14-member dance company, an orchestral score by Andrew Culver (inspired by Cage) performed by 150 musicians that included the St. Cloud Symphony Orchestra, and an electronic score by longtime Cunningham collaborator David Tudor. The performance was truly one of contemporary dance’s epic achievements. It was filmed by Charles Atlas and released in 2011.

Unfortunately, John Cage was unable to realize this composition, as he passed away on August 12, 1992. However, for Cunningham, the event was one of the artistic highlights of his life. Cunningham passed away on July 26, 2009, less than a year after the epic performances. He was 90 years old.

This is a very good video put out by the Walker Art Center as part of their 2017 exhibit Merce Cunningham: Common Time:

Here’s one more for the road. The album John Cage meets Sun Ra was recorded in 1986 at Sideshows by the Seashore in Coney Island and released by Meltdown Records in 1987:

I think it’s a fitting place for a meeting of such quirky artists, viewed by many in the mainstream as “freaks”. But while I agree that music is in the ear of the behearer, both artists were undoubtedly two of the most fearless and innovative artists of our times.

Here’s a short video with interesting concert footage put out to promote the 2016 album reissue released by Modern Harmonic:

One of the tracks on the album has both Cage and Sun Ra silent for two and a half minutes, which makes me think it can be harder to listen soft than loud. However, I do admire Cage’s passion for silence, which may have come from personal roots.

Cage was a lonely, precocious child, mocked by classmates as a sissy. “People would lie and wait for me and beat me up,” he said, in a rare comment on his personal life, shortly before his death. I suspect these experiences helped fuel his idea that noise and rhythm rather than melody and harmony could be the basis for music. Perhaps it was this silent grit that fueled his ground-breaking innovations and led to the formation of this country’s earliest percussion ensembles.

Like Cage, Cunningham was also a fierce innovator and not without critics. That is understandable. When you choose to dance in an environment that has no real connection with the music and is also derived by chance, the conventional wisdom is the art may suffer from a lack of verve or a sense that the artist is not actually engaged - not fully present and that big parts of their being were not invited to the party. This might be why so many people get turned off.

Brian Eno once said:

These people are not “making a record”, they are making music because it creates for them a world they want to inhabit, makes them feel alive, and that life floods out over the edges of the recording and into you, the listener. And that, I’m starting to think, should be an artist’s minimum ambition.

However, when you walk away from your home and tradition and choose to live on the outskirts of town, that path doesn’t make your life any less real - harder perhaps but no less real. So in that regard, it’s understandable for people to hate it or love it and look at it as either a put-on or genius. It just depends on what side of town you call home. If you ever journey to the outskirts of town, maybe that’s when the work of John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and Sun Ra starts to sound like home…

Next week, on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles in and explore the world of John Cassavetes.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Wow…all brand new and very cool stuff. I walk by Cornish 1x a month these days when I visit my hometown, Seattle, to see my dad.

Every time I read one of your pieces, I scratch my head about all the time I spend reading other stuff on here that I don’t like as much.

I’m a big Cage fan, and I know his work and ideas fairly well, but I’m not an expert and there was much new information here for me. I’m saving this article and I look forward to having time to watch and listen to all these well-curated clips.

The cassavettes piece sounds enticing too— I’ll try not to miss it. I’ve seen a bunch of his films but I’m sure you’ll find some stuff that’s new to me.