Incus a new, independent record label established and operated by the musicians, for the musicians.

-Evan Parker

I send this from across the pond, in Farnborough, a small town about an hour and a half southwest of London, where I am visiting my relatives.

My mother was born in London in 1932. She met my dad at an Air Force base in London during the Korean War. In 1952, they were married at St. Alban, an ancient parish church located near the River Thames, in the heart of Teddington, a suburb of London.

In 1953, they had a son, Paul, my oldest brother. After the war, they sailed on the SS United States and landed in New York City. They took a train to Denver and moved to Boulder, Colorado. Some years later, in 1962, I was born in Sacramento, California.

So I have half English blood in my veins.

This explains why, even though I feel almost completely American, I have always had an attachment to European jazz; however, mostly just the Dutch and German scenes. For some odd reason, the UK scene lurked in the background. It took me a while to notice and appreciate the British improvisationists, who I explored over the past three weeks of our journey.

As I look back on it now, I think even The Wire magazine, which I cut my jazz teeth reading while stationed in the Netherlands and West Germany in the second half of the 1980s, seemed more interested in covering the American rather than the European jazz and in particular the British jazz.

Until the tragic loss of John Coltrane in the summer of 1967, that Big River called Jazz was dominated by its African-American roots, which allowed few contributions from Europe. That doesn’t mean European artists weren’t busy developing their own music; in fact, all the while a new musical revolution was brewing across the pond. By the middle of the 1960s, European jazz musicians were developing specific personalities and in 1968, decisive steps were made.

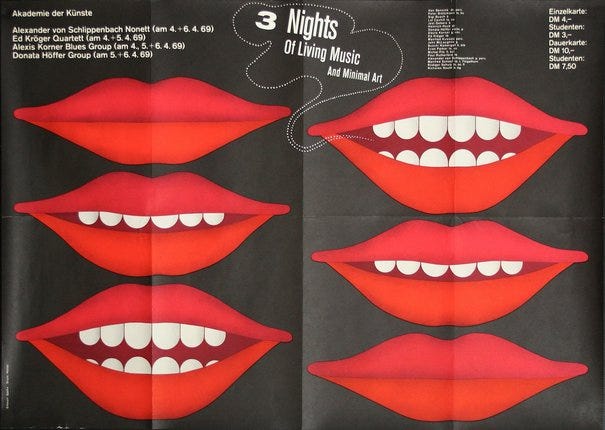

That summer in Berlin, a collection of musicians organized an alternative program to “Jazz am Rhein.” They called it “Total Music Meeting.” The first meeting was called “Three Nights of Living Music and Minimal Art:”

It was held at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin. One of the groups was the Alex von Schlippenbach Nonett with musicians from both continental Europe and the UK. British guitarist Derek Bailey played in the Nonett.

The following year in March, again at the Akademie der Künste, the meeting was called “Workshop in den ausstellungsraumen freie musik” (Free music workshop in the exhibition rooms) - now just known as Workshop Freie Musik No. 2. It featured a group called Music Improvisation Company that again included Bailey on Guitar; however, this time also included British artists Evan Parker on saxes, Hugh Davis on electronics, and Jamie Muir on drums.

Back in London after this workshop, Bailey and Parker, with Dutchman Han Bennink, recorded the first Incus record, and a new independent record label established itself at the heart of a new musical revolution.

This week on that Big River called Jazz, our journey is dedicated to the world of the British label Incus.

Musician-owned and operated music labels started with American jazz artists Charles Mingus and Max Roach’s Debut label in 1952, Sun Ra’s Saturn label in 1957, and later followed by Amiri Baraka’s Jihad Productions in 1965, and Don Pullen’s SRP in 1967.

Following in the footsteps of these American labels, the independent Dutch Instant Composers Pool (ICP), and German record labels like Peter Brötzmann’s Brö and Jost Geber’s Free Music Production (FMP), Bailey and Parker started their own independent music label in the U.K., Incus Records.

However, establishing independent musician-owned record labels was not the important part of a grander revolution in Europe in the late 1960s. The more important point was the personal decision by a musician to stand on their own two feet. For example, the decision by a tenor saxophonist to stop playing “like Coltrane.”

The detachment of European Free Jazz from American Free Jazz was not an event with a fixed date, it was a process. Although albums document a moment or a stage in that process, they don’t represent the process, which developed slowly over time. Like FMP in Germany, Incus Records in the UK played an important role in documenting that emancipation process - decoupling European Free Jazz from American Free Jazz.

Incus Records was the first British musician-run independent record company. It was founded in 1970 by Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Tony Oxley, and Michael Walters. Oxley and Walters left early in the label's history. Bailey and Parker continued as co-directors until the mid-1980s when friction led to Parker's departure. Bailey continued the label with his partner Karen Brookman until he died in 2005.

Incus was primarily conceived as a medium for Bailey and Parker's activities in improvised music, occasionally issuing work of other musicians either through their association with Bailey and Parker or as a reflection of their admiration. The commitment to improvisation in music fully characterized the label.

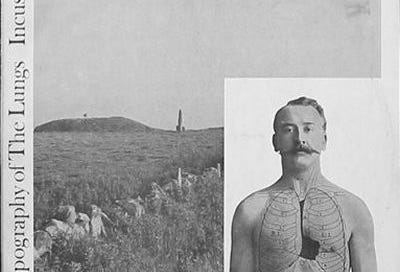

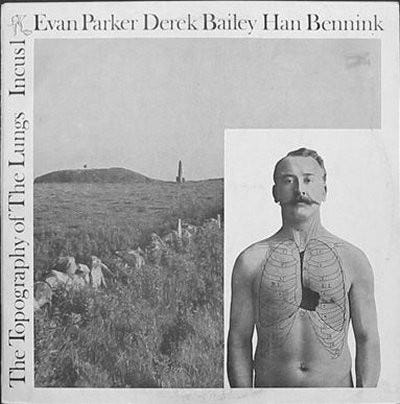

Incus Records’ first album was released in 1970 as The Topography Of The Lungs. It was recorded in London on July 13, 1970:

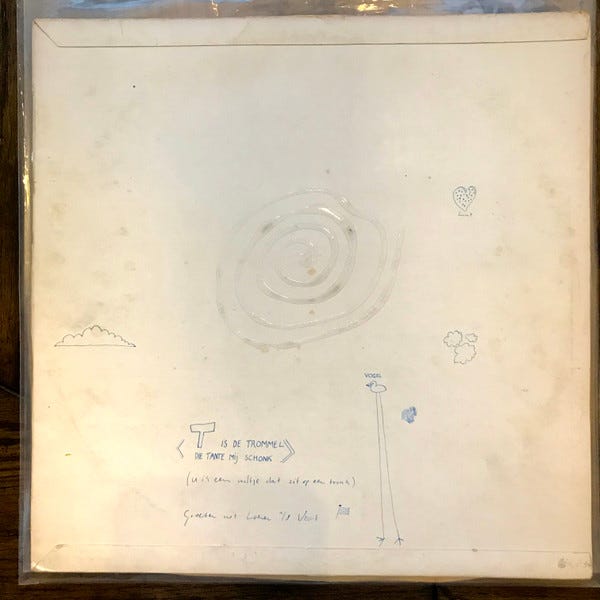

This is a trio album with Bennink on drums, whom Bailey and Evans had played with as part of the Peter Brotzmann Group at the Workshop Freie Musik No. 2. Bailey had also played with Bennink in the summer of 1969 at Studio Andre van de Water in Nederhorst den Berg, The Netherlands. That session was the Dutch ICP label’s fourth release. Sleeves from a small part of the album’s first edition were handmade by Han Bennink. Here’s one of my copies:

Inspired by the Fluxus art movement, the ICP was formed in 1967 as a co-op by Han Bennink, Misha Mengelberg, and Willem Breuker to promote avant-garde Dutch jazz performances and recordings. The idea of selling their music was strictly a tool to fund their next release.

I’m sure that Bailey was in some ways inspired by, if not envious of, the Dutch ICP’s overall commitment and organization around documenting their music. In England at the time, the record-making process was in disarray.

In a June 1979 article in Coda magazine, Peter Riley wrote:

Vast fortunes had been won and lost in the rock explosions at such an alarming rate that record promoters were quite frenetically trying to keep pace with the music. By the end of the decade rock itself was trying out all sorts of new formats, so that the big-label promoters, completely lost in this sudden profusion of new styles, became willing to give almost anything a try. One result of this was the commercial market’s brief flirtation with improvised music.

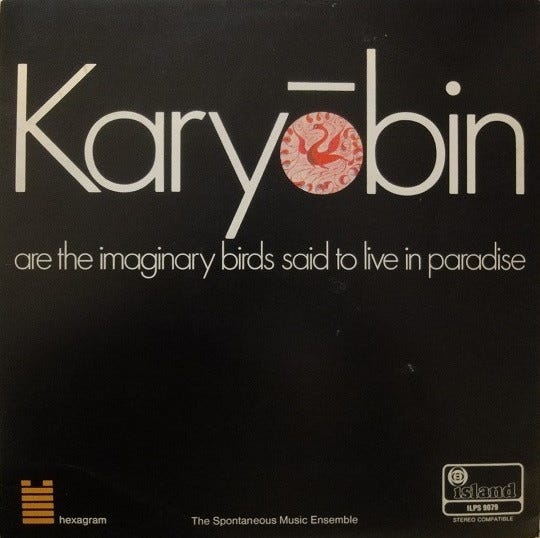

As a result, some historically implausible records were released by commercial companies. Perhaps the best example of this was Island Records’ 1968 release of the Spontaneous Music Ensemble’s Karyōbin:

We covered this a couple of weeks back, but here it is again:

However, it didn’t take long for the big labels to discover how uncommercial this music was and drop them like a rock.

In that same Coda article, Riley wrote:

But perhaps what offended most was the speed at which the records issued were removed from the market and became totally unobtainable. Tony Oxley had some particularly bad experiences with records issued by CBS which seemed to be deleted almost as soon as they were issued, in what is assumed to be some kind of tax-loss dodge.

In the end, Bailey and Parker formed Incus to avoid the compromises of working for major companies while building their free improvisation archive. In a 1985 The Wire interview, Bailey concedes:

I have put things out on Incus which I couldn’t possibly have put out on any other label.

If you want to make a record for another record company, you have to go to them with your hat off and say, ‘Please, sir’ or, ‘This is a really attractive project…’ To make that another built-in characteristic on top of all the other insecurities of a musician’s life is just one thing too much. At least we’ve got the record side of things sorted out in a way which satisfies us. We can make all our own decisions: nobody tells us when the “market” is ready for our next “product”.

Perhaps the best way to highlight the Incus catalog is to present a few of my favorites.

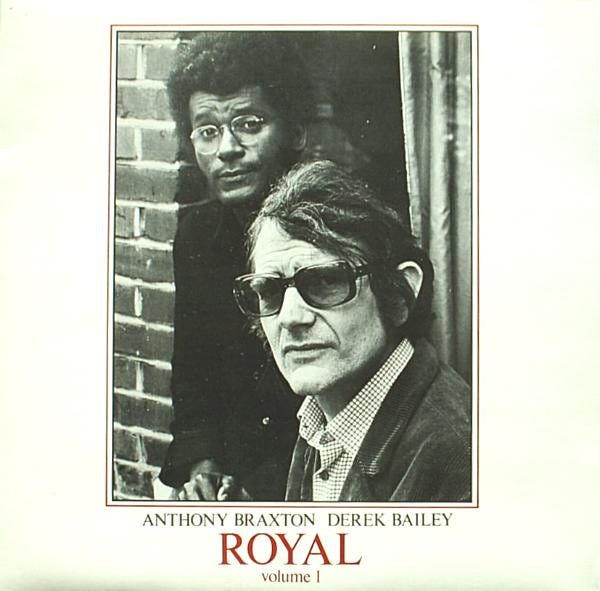

For example, Royal was recorded live at the Royal Hotel in Luton, England on July 2, 1974; however, the record was not released until 1984 as Incus 43. Anthony Braxton joined Derek Bailey in a strong performance:

Here’s the entire album:

Incidentally, the concert's second part was supposed to be available on Incus 44. The catalog number was allocated, but it was never released. Honest Jon's Records in London reissued these recordings in 2017 as Royal (Volumes 1 & 2).

In the mid-1970s in Paris, Bailey met American cellist Tristan Honsinger, who later recalled:

At that time it was pretty hardcore improvised music, as I remember. Not too much composition except Misha (Mengelberg); I became a part of his tentet, which brought a new aspect to my idea of improvised music. But Derek was always: “No music, just play.”

Bailey invited Honsinger to London, and on February 7, 1976, they recorded Duo, one of my favorite Incus releases. It was released that same year as Incus 20:

From that album, here’s an excerpt of their opening track The Visit:

The recently passed Honsinger is outstanding. You can read more about him here:

In 1976, Derek Bailey founded Company, a pool of free improvising musicians - not a fixed group but an assortment of musicians who came together from time to time under Bailey’s leadership. Company is perhaps best known for its yearly Company Week when nine or ten musicians performed improvisation together for six days in London. The first Company Week took place in May 1977 at London’s Institute of

Contemporary Arts.

Often, the artists involved in Company Week had not played with each other previously. Incus documented the meetings, and the first release was naturally Company 1, recorded in 1976 by Bailey, Parker, Honsinger, and Dutch bassist Maarten van Regteren Altena and released as Incus 21. They played four trios in the four possible trio combinations.

Here is that album:

Incus released many more Company albums, all completely improvised. Bailey did 17 years of Company Week and then suddenly stopped. In a September 2004 interview in The Wire magazine, he explained:

I did 17 years of Company Week and then suddenly I could see it all in front of me, all mapped out, these anniversary things coming up, you know, 20 years of Company! 25 years of Company! All that bullshit. And I thought, I’m not going to go through with that.

In some ways, this may explain why Incus Records stopped releasing albums in 1987. Their last release was Incus 52: Steve Noble and Alex Maguire’s Live at Oscars, recorded as part of the Bracknell Jazz Festival on the 4th of July 1987.

Incus Records stayed true to its aim - the art supports the economy. This idea, that records exist only to honor the music, is a hallmark of musician-owned and operated music labels.

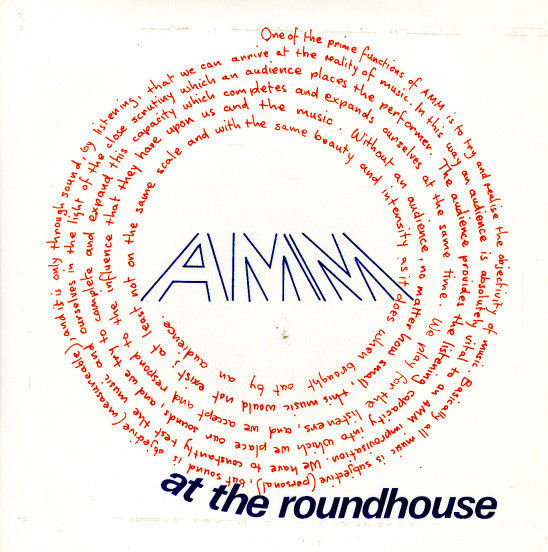

Here’s one for the road. As far as I know, the Incus label released only one 7” EP, AMM at the Roundhouse, recorded in August 1972 at the ICES festival (International Carnival of Experimental Sound), an avant-garde music festival in London:

The group was initially composed of Keith Rowe on guitar, Lou Gare on saxophone, and Eddie Prévost on drums. The three men shared an interest in exploring music beyond the boundaries of conventional jazz. AMM made an important impact on improvised music in Europe, although it never achieved widespread popularity.

The group recorded their first album Ammmusic in June 1966, even before Brötzmann recorded Adolphe Sax on his BRÖ label in 1967, which musicologist Ekkehard Jost described as “the first German, probably even the first European jazz record, which consequently pursued the concept of total improvisation.” I should add that although AMM’s music is improvisational, it is nothing like the ferocity of Brötzmann’s two BRÖ releases.

Here’s Ammmusic’s first track, Later During A Flaming Riviera Sunset:

Interestingly, Ammmusic was released by the Elektra label, which by the late 1960s had success with mainstream artists like The Doors, Judy Collins, and Bread.

On the back of the AMM at the roadhouse EP, it says:

The meaning of the letters AMM has been the source of much speculation. They serve the players by reminding them of the early ideas of the group. An interesting attempt at guessing their meaning came from one of the audience after a concert in New York (Nov 1971). He sais that the name must be “Audacis Musicae Magistri.” However, in latin that means The Masters of Audacious Music, which would be MAM.

In a 2001 interview, AMM’s guitarist Keith Rowe was asked if AMM was an abbreviation. He replied, "The letters AMM stand for something, but as you probably know, it's a secret!"

Maybe it’s this type of sensibility that kept British free improv and labels like Incus in the shadows for so long…

I guess these last three journeys have been for me a type of coming home. An acknowledgment of the half-English blood in my veins, and it is only fitting that this final journey is sent to you from England.

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of European emancipation in jazz.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

I came across this site via Google. It was listed as a hit on my search term Tony Oxley incus8. This Tony Oxley title gets excellent reviews and seems to have been very influential. Unfortunately it is not available on CD. Vinyl versions are hardly available. I have tried to contact the label INCUS. But the contact information that I find on the internet seems out-of-date. Can anyone help? Thanks, Eddy

That's AMM at the Roundhouse not Roadhouse. So called as it is an ex railway turntable shed used to re-orientate locomotives. The venue for many "happenings" in 1960's North London.