Henry pulled the strings like a lion. He had the biggest sound in the business. Henry had a bigger sound in the days before amplifiers than all the cats you hear today with amplification. And the heart and personality, too.

-Burton Greene

My journey back to the late great bassist Henry Grimes was a circuitous one that started a few years ago.

While researching the stellar but all too short career of Tina Marsh and the Creative Opportunity Orchestra (CO2), I came across their amazing 1994 CD The Heaven Line. I noticed that Dennis González plays trumpet on that session.

I had not heard of González. I started to look into him and ran across his Nile River Suite, recorded in November 2003. I was surprised to see that Henry Grimes played bass at this session. It was Grimes’s first recording in more than 35 years. Nile River Suite begins with a beautiful duo with Grimes and late trumpeter Roy Campbell, Jr. Our eternal love goes out to both Grimes and Campbell as we listen to this wonderful performance:

After listening to this suite, it occurred to me that Henry Grimes had found his way back on the jazz scene, and I didn’t even know it. Like the Phoenix, with wings of gold and jewelled plumage, Grimes had risen from his ashes, more magnificent than ever.

This week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the life of Henry Grimes, one of the most mysterious in jazz.

From his heyday at the forefront of New York City’s jazz scene in the late 1960s, Grimes entered into creative exile and slipped into obscurity. It was commonly assumed Grimes had died. However, in 2002, a social worker and jazz fan from Georgia set out to discover Grimes's fate once and for all.

Miraculously, he found Grimes alive in a tiny apartment in Los Angeles but nearly destitute and without a bass to play. He was writing poetry and doing odd jobs to support himself. Although he had fallen out of touch with the jazz world, he was eager to perform again.

Word of Grimes’s rediscovery spread quickly, and soon he was back in New York City. He was met with a hero’s welcome, his first of many, on May 24, 2003, when he lugged an upright bass onstage at Old St. Patrick's Youth Center in SoHo as part of the eighth annual AFA Vision Festival. It had been 35 years since Grimes last played in New York City.

Two days later, at the Mulberry Arts Center in New York City, Grimes and young bassist Nick Rosen played a memorial tribute to singer Jeanne Lee:

A few months earlier, Nick Rosen, a seventeen-year-old senior at The Oakwood School in North Hollywood, California, arranged a meeting with Henry Grimes at The Pantry in downtown Los Angeles.

As the story goes, Rosen, a troubled youth, had been a student in Steven Isoardi’s ninth-grade Social Studies class. Rosen expressed interest in learning to play the bass, so Isoardi arranged lessons for him with bassist Roberto Miranda, a Los Angeles musical treasure.

During the fall of his junior year, 2001, Rosen took Isoardi’s course in African American Music and Society, where he learned about Albert Ayler. For his senior project, he wanted to meet and perhaps take a lesson with someone who had played with Ayler. His first choice was Henry Grimes. However, Isoardi sadly informed him of what the jazz world thought it knew—that Grimes had passed away during the 1980s.

A few weeks later, during winter break, Isoardi noticed an article in the 2003 issue of Signal to Noise magazine: Henry Grimes: The Signal to Noise Interview by Marshall Marrotte. He was stunned. What? Henry Grimes was alive and living in Los Angeles!

Isoardi wrote about Grimes’s rediscovery in his Current Research in Jazz article, The Return of Henry Grimes: A Memoir:

During 2002, Marshall Marrotte, a social worker and Henry Grimes fan from Georgia, had embarked upon a quest to discover the last resting place of the bassist. Instead, after much searching, he found Henry living in a single room #335 at the Huntington Hotel, 752 Main Street, in downtown Los Angeles, just on the boundary of L.A.’s homeless city-within-the-city encompassing some of the meanest streets in the state. For the past thirty or so years, the bassist had led a marginal existence, punctuated by occasional periods of homelessness, surviving through janitorial, construction, and day labor work. The bass had been sold long ago, and Henry’s last memories of the music world dated from the late 1960s. He did not know what a CD was and he was unaware that many of his fellow artists, including Albert Ayler, had died. The interview concluded with a note from Marrotte asking those who might assist Henry to call his home in Georgia.

Isoardi called Rosen immediately and told him, “You won’t believe this. Not only is Henry Grimes alive, but he’s living in downtown Los Angeles.” He passed on to Rosen Marshall Marrotte’s number, who, within an hour, called him back saying, “I’ve been on the phone with Marshall. He gave me Henry’s address and the desk number at the hotel - they don’t have phones in the rooms.” For the next two weeks, he called the Huntington Hotel desk every day, leaving messages, asking the desk staff to make sure Mr. Grimes received his messages, and then pleading with them to post the messages on Henry’s door. Finally, around the end of January, Grimes called Rosen and they arranged to meet for lunch at The Pantry.

At lunch, Rosen learned that a few weeks earlier, Grimes had received a bass, sent to him from New York by renowned musician William Parker, and was playing again. With Grimes’s permission, Rosen wanted to help with his return to music and arranged a session with some of the finest musicians in the area.

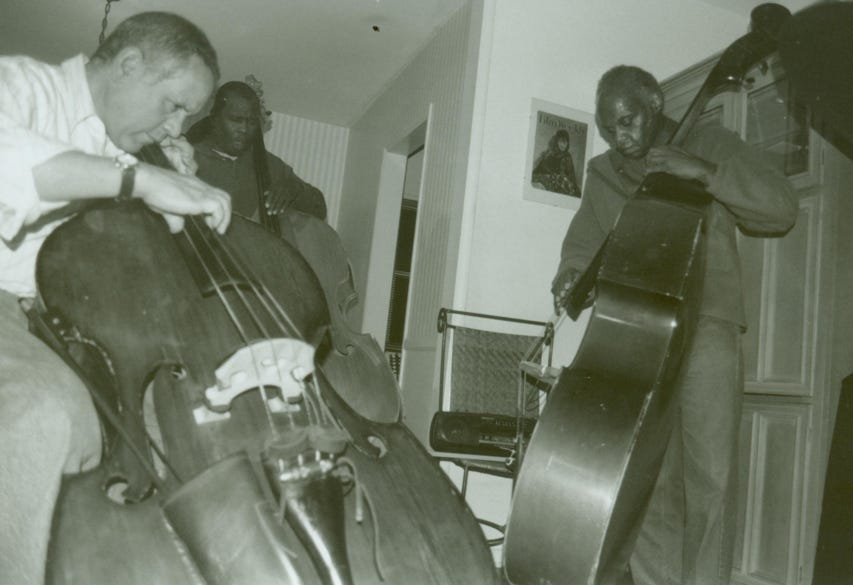

The result was a Sunday evening, February 9, 2003, jam session in the front room of Rosen’s mother’s home in Van Nuys:

According to Isoardi’s article:

Henry spent the night at Nick’s, and, after a full breakfast, accompanied him to school the following morning. Young saxophonist Joey excitedly proclaimed it the best carpool experience in his years at Oakwood. Nick had arranged time and an honorarium with our principal to have Henry speak at our Monday morning “Town Meeting,” a regular “open mike” forum for the entire school community, to be followed by a question-and-answer session and a performance of improvised music by Henry, Nick, and Joey at lunch in the music department. They arrived early, briefly visiting my tenth grade class, before Nick introduced Henry to the approximately five hundred people gathered at the assembly. Henry spoke briefly, but clearly and directly about the importance of the music and his willingness to entertain whatever questions students might have at their lunchtime performance.

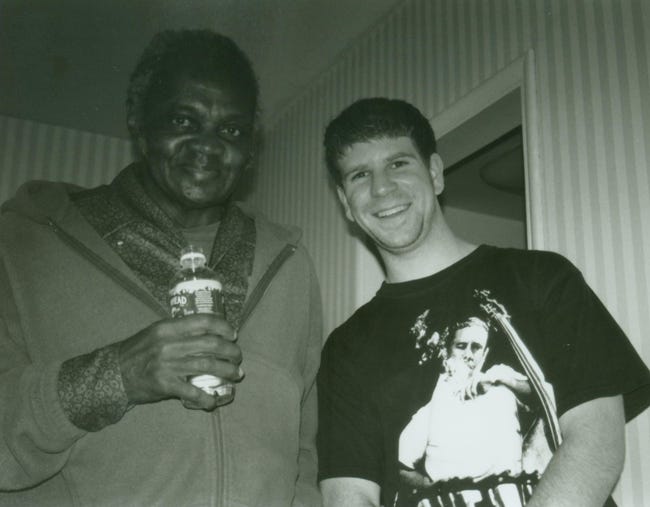

After this jam session, things moved quickly for Grimes. Rosen became his manager and started drumming up local gigs. Here they are together at the Rosen family home during that first jam session:

On Sunday, March 30, Rosen brought Grimes to the Jazz Bakery to meet The Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra and their choir, The Great Voice of UGMAA, who were there to offer the Third Annual Tribute to their late leader and founder, Horace Tapscott, who passed away in 1999. And by May 2003, Grimes was playing at the New York Vision Festival.

On the final evening, Rosen and Grimes played together, as heard in the video above. Grimes would soon move permanently to New York City, and the rest is history.

Incidentally, Steven Isoardi would go on to write The Dark Tree: Jazz and the Community in Los Angeles, published in 2006 by University of California Press.

Henry Grimes’s life as a musician started with the violin in Philadelphia, a milieu from which players such as Sunny Murray, Lee Morgan, and Archie Shepp also emerged. Born in 1935, Grimes got his start as a professional musician as a teenager in the early 1950s, playing R&B gigs. Simultaneously, he studied classical music at Juilliard, commuting regularly between Pennsylvania and New York. Juilliard led to an exclusive focus on the double bass. He supplemented this with private lessons with Frederick Zimmermann, principal bassist for the New York Philharmonic and teacher of David Izenzon, Barre Phillips, and other renowned bassists.

In 1953, he gigged with Arnett Cobb and Willis Jackson. In 1957, he played with the Gerry Mulligan quartet and also with Charles Mingus and Thelonious Monk. Here he is with Monk and Roy Haynes from Jazz On a Summer’s Day from the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival:

Yet, at the same time Grimes was making waves as a go-to straight-ahead bassist, he was increasingly becoming fascinated by and active in the nascent New York free jazz scene.

Grimes’s later definitive statements of the New Thing as an accompanist with Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, and Pharoah Sanders are all well documented; however, I’d like to highlight three key earlier moments that I feel helped fuel this later free work.

The first was in 1959, when Grimes accompanied Sonny Rollins as part of a trio on a European tour. This was the first time Grimes was in a band where he was the only harmony instrument - a true test and challenge of his ability.

From the album, St Thomas - Sonny Rollins Trio In Stockholm 1959, here is How High The Moon:

Rollins was always an advocate of the American Songbook. For a deeper look at that, I wrote about him here:

Sonny Rollins

I like melody, and people I think have an affinity for melody. It strikes someplace in the brain, in the cortex. It stays there and people remember it. It’s a way of associating memories of life’s events and so on. The American songbook was primarily melodies.

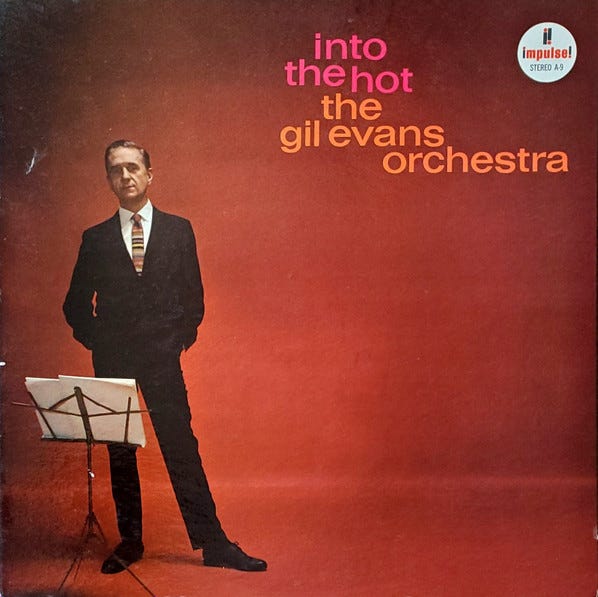

The second was an October 31, 1961, session as part of the Cecil Taylor Unit on Gil Evans' album Into The Hot:

From that album, here is the Cecil Taylor composition Pots:

During this session, Grimes was starting to explore bass in an open format. According to Phil Freeman of Burning Ambulance, in his extradorinary book, In Brewing Luminous: The Life & Music of Cecil Taylor, Grimes’s work with Taylor included “some of the pianist’s most exploratory and compositionally brilliant music, including the 1961 session that yieled Taylor’s half of the album Into The Hot and two Blue Note albums, Unit Structures and Conquistador!, from 1966.”

Interstingly, 40 years later, in October 2006, Grimes would play again with Taylor and drummer Pheeroan akLaff in a trio Taylor dubbed AHA 3. They only performed a handful of concerts widely regarded as the most exciting trio music Taylor had made in some time. They reunited once more in March 2007, for a performance at Lincoln Center’s Rose Hall, co-billed with John Zorn’s quartet Masada.

The final key moment was on February 24, 1964, at Atlantic Studios in New York City, when Grimes played on one of my favorite Albert Ayler albums, Swing Low Sweet Spiritual. From that album, here is Deep River:

The first two moments allowed Grimes to play freely with confidence and without inhibition. The album was released on the Dutch Osmosis Records in 1971, but by that time, Grimes was already long gone, somewhere in California.

After recording all these seminal avant-garde sessions in New York, Henry Grimes found the financial realities bleak. He decided to move to California in 1967, where he continued to play for a short time in San Francisco with Lambert, Hendricks, and Ross. He also hoped to make a go of it in the movie business as an actor and session musician, but that didn’t pan out. The closest he may have gotten to the movies was playing on Walt Dickerson Quartet's solid album Jazz Impressions Of Lawrence Of Arabia. Recorded in March 1963 in Gotham Studios, New York City, here is Arrival At Auda's Camp:

Incidentally, Ahmed Abdul-Malik also plays bass on a couple of songs on this album. We’ll catch up with him a little further down the river…

Grimes stayed in San Francisco for about a year and, in 1969, moved to Los Angeles. When he got there, he sold his bass and made the conscious decision to drop out of the jazz scene. He worked a lot of day labor jobs, construction-type things, and lived in a Mission on and off before moving into a small apartment. In a 2003 interview with Ken Weiss for Cadence magazine, when asked if he ever thought about getting back into jazz in Los Angeles, Grimes responded:

Esthetically, which is to say the only thing I thought about was playing and not making money. I would have played if the conditions were viable but they weren’t and I just didn’t feel like trying to make deals for myself. That can be difficult.

Unfortunately, it seems that many of the reasons that kept Grimes away from jazz in California were the same reasons that drove him away from New York City.

Then, in 2002, out of nowhere, he was rediscovered.

Here’s one more for the road. In November 2010 at The Stone, back when it was at Avenue C and 2nd Street in New York City, Henry Grimes and a young Max Johnson played a bass duo set as part of a month of music curated by Grimes. Here is that performance:

I think the backstory of this performance helps us understand Henry Grimes, the man, more than the bass player. Max Johnson tells that story:

After a year in college where my (unnamed) bass teacher told me to quit because I’d never be any good, I had pretty much decided he was right. But at a concert I went to to celebrate my 19th birthday, I went to hear the great Henry Grimes. I knew of Henry through his work with the wonderful Perry Robinson, and the concert I saw that night at the Vision Festival was also the first time I heard William Parker, Kidd Jordan, Marshall Allen, the Sun Ra Arkestra, Warren Smith, Hamid Drake, among many others, and changed the way I saw free improvisation. I went back to the Vision a couple days later on my actual birthday to hear Henry play solo, and after his set, I approached him sheepishly telling him how much of a hero he was to me, and asked him if he taught lessons. His wife Margaret, quickly rushed over and answered for him, telling me he indeed taught lessons, and gave me their business card, and a sparkly pin with a picture of Henry on it (which I still cherish). Afterwards Henry said, "Thank you", and that may be all I heard him say that night after the set.

My first lesson in their east-side Manhattan railroad apartment started with Henry and I playing duo... which lasted for about two hours straight. I'm sure I didn’t even have 5 minutes to say musically, let alone 2 hours, but afterwards he said a few encouraging words then we sat quietly for a few minutes and started to play again. This time he would stop me every few minutes and tell me to keep going with certain ideas, or to not jump from one thing to another so quickly, or follow his lead some places and lead other places. He was very patient and encouraging, and improvised with me like I was a real improviser, not a kid, even though I hadn’t even played the upright bass for a year at that point. Over the next 5 or so years, I continued taking lessons with Henry in exchange for driving him and his bass to gigs, letting him borrow my bass on occasion, transcribing his tunes from 60's records so they'd have a copy of them, and helping with whatever I could. Eventually the lessons stopped being lessons and we'd just play duo for hours, mostly playing free, but sometimes playing standards or his tunes from the 60’s. We'd sit and listen to WKCR together, I would get (small pieces of) stories about Sonny Rollins, Don Cherry, Albert Ayler and Cecil Taylor, and try to soak up as much knowledge as I could.

This recording was made [when] I was 20 years old and had been playing the upright bass for about two years at this point, and in retrospect, am still amazed that Henry asked me to play this concert with him. It was like being called up to the big leagues! It was truly one of the most important moments in my life as a young bass player. I recall there being about 10 people in attendance, but I didn’t care, I was getting to perform in duo with my hero after a year and a half of playing at his apartment together. I certainly hadn’t matured into a unique musician yet…

The digital album is called Olive Oil, the name Henry gave the green upright bass that William Parker sent him:

The story of Henry Grimes is an extraordinary tale. It reminds me of the Oscar Peterson tune When Summer Comes. Before he plays the song, Peterson says, “…according to the weather, I should have titled it, if summer comes.” Oh, but summer always comes.

In 2002, summer came for Henry Grimes as he started a legendary comeback that stretched more than 15 years. This was an improbable third act that lasted until his death on Wednesday, April 15, 2020, at Northern Manhattan Rehabilitation and Nursing Center in Harlem. He was 84 years old.

Perhaps a little further down the river, I can spend more time focusing on the wonderful work Henry Grimes recorded after his return to New York and spend more time recognizing the important folks who helped him along the way.

I think Isoardi provides another prescient summary of Henry Grimes, the man:

There are many layers to this story. Certainly the return of a great artist is the most prominent and is story enough. But there is also the re-emerging elder giant meeting the young neophyte, also with a difficult past… All of them grew enormously as artists and as people. As this story was unfolding, Oakwood’s headmaster, James Astman, observed, “Nick (Rosen) has done something remarkable and wonderfully humane.” And much was done by Henry for Nick, for all of those who contributed to make this a success, and for fans of good music everywhere. Henry’s life was changed and his career re-launched, and perhaps Nick has found his direction in life.

I find Grimes’s loyalty and willingness to mentor young bassists like Nick Rosen and Max Johnson, to name just two, a window into his big heart.

Finally, here’s a priceless, short documentary with Grimes talking about and reading some of his poetry and playing Olive Oil:

Keep your eyes and ears open, you never know where that deep river called jazz will lead you…

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of Tina Marsh and the Creative Opportunity Orchestra.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Great read -- many thanks! A lot of details on Grimes' rediscovery I wasn't aware of yet.

A personal favourite is the work Grimes did with Marc Ribot on the albums Spiritual Unity (2005) and Live at the Village Vanguard (2012). Very moving to hear him play "Ol'Man River" on that latter album (with a wonderful solo), a song he had also played on with Ayler on the Swing Low Sweet Spiritual album.

Looking forward to the next stretch on the river.

Wonderful read on Henry. I have some recordings with Marshall Allen and Henry Grimes from the 2005 Spaceship On The Highway tour, beautiful music.