Henry Flynt

From culture to veramusement...

Rock became an incredible commercial success, people just became bored with serious music, and it was forgotten.

-Henry Flynt

On July 13th, Table of the Elements had a relaunch party at P.I.T. in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. It featured Everloving, “the debut from the NYC ‘star-studded’ Henry Flynt tribute band.” On that day, they offered a free download of Everloving’s Hillbilly Jive. To help support Table of the Elements via Kickstarter and to listen to the song, go here.

Bandcamp describes Everloving this way:

Everloving is a triumphant singalong and clangorous Huzzah! from a like-minded gathering of pickers, fiddlers, and tub-thumpers who each reject designations, ossifications, and highfalutin encapsulation. In celebrating the essence of Henry Flynt, they assert collective agency with the low-down, hoe-down abandon that our tumultuous era demands.

The name of the group is obviously a take on Henry Flynt’s song You Are My Everlovin’ and the first four minutes of their Hillbilly Jive is a reflection of the song itself:

Highly critical of established institutions of “serious culture,” philosopher, composer, and violinist Henry Flynt occupies a unique place in the history of experimentalism in the United States. Beginning in 2001, he released a string of recordings spanning modernist sound experiments, hillbilly fiddling, rawkus garage rock, and Hindustani-inflected solo violin improvisations. His music, which might be characterized as “minimalist country,” is an attempt to fuse hillbilly music with the avant-garde. Produced between 1963 and 1984, these works provide a wonderful opportunity to reexamine the history of experimental music in the U.S.

While studying mathematics and philosophy at Harvard in 1959, he began composing music and met composer La Monte Young. Through Young, he entered into the epicenter of the New York Post-War Avant-Garde. In Flynt’s words, at that point Young was “running the scene in New York.”

In 1960, Young invited Flynt to Yoko Ono’s Chambers Street loft, where Young organized a performance by Terry Jennings as part of a series that ran there between December 1960 and June 1961. The series featured performances by John Cage, David Tudor, Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Jack Smith, Tony Conrad, and John Cale. I wrote about Jennings here:

That performance was Flynt’s first time alone in New York City. He would soon move to the city and remain part of the Downtown avant-garde and sectarian Left.

In February 1961, as part of Young’s series at Ono’s loft, Flynt performed one of his early compositions, Music and Poetry of Henry Flynt, a piece for prepared piano played using fists and forearms. You can hear them at the 54:15 minute mark of this June 20, 2013, WKCR radio broadcast. Although the original tapes were lost, Flynt recreated those performances in Germany earlier that year. The acoustic violin piece will play first, followed directly by the prepared piano piece:

By the time of the loft performance, Flynt had flunked out of Harvard and was active in the New York avant-garde scene. So the jazz-influenced improvisation piano piece above, with no score and “bad notes,” brought a radical sensibility to the classical world and foreshadowed the anti-art movement he championed in 1962.

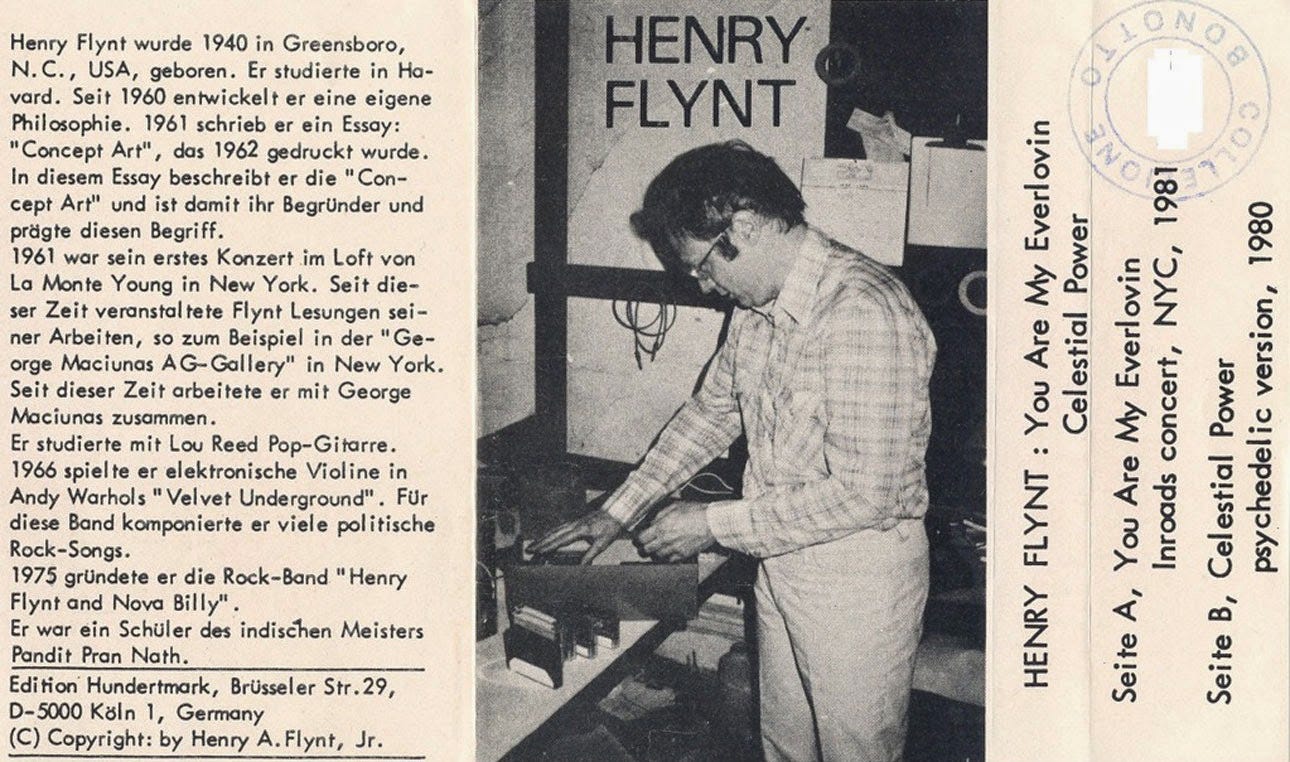

With the single exception of a cassette released in 1986 in an edition of 350 copies by Cologne’s Edition Hundertmark, Henry Flynt’s music didn’t see commercial release until the 21st century. And then, at the century’s turn, the floodwall gave. Within three years, three American independent record labels had released ten compact discs featuring hours of archival recordings of Flynt’s music.

This week on that big River called Jazz, our journey is dedicated to the world of Henry Flynt.

Henry Flynt was born in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1940. His father was a portrait photographer, and his mother was a schoolteacher. He grew up with a classical music education with an emphasis on modern music. In 1957, at the age of 17, he enrolled at Harvard. While there, he also discovered what they called new music, International Style, and Cage. However, he dropped out of Harvard to formulate general theories of the creep personality. He began working on this theory five years after Helen Lefkowitz, a fellow student at the National Music Camp at Interlochen, Michigan, had rejected his teenage advances by describing him as “such a creep.” Recoiling from his humiliation, Flynt, a self-described veritable personification of a creep himself, began his systematic investigation of “the creep problem.”

On May 15, 1962, composer Christian Wolff, then a student at Harvard, organized a lecture by then twenty-two-year-old Flynt. The lecture analyzed the social misfit known as the “creep.” In the august upper commons room of Harvard’s Adams House, while standing before a massive library table situated authoritatively on an oriental rug, Flynt delivered his lecture, “The Important Significance of the Creep Personality.”

Flynt’s discussion of the social construction of culture and personality evolved into a philosophical theory of opposition that developed into an anti-art campaign. His theory soon developed into a movement.

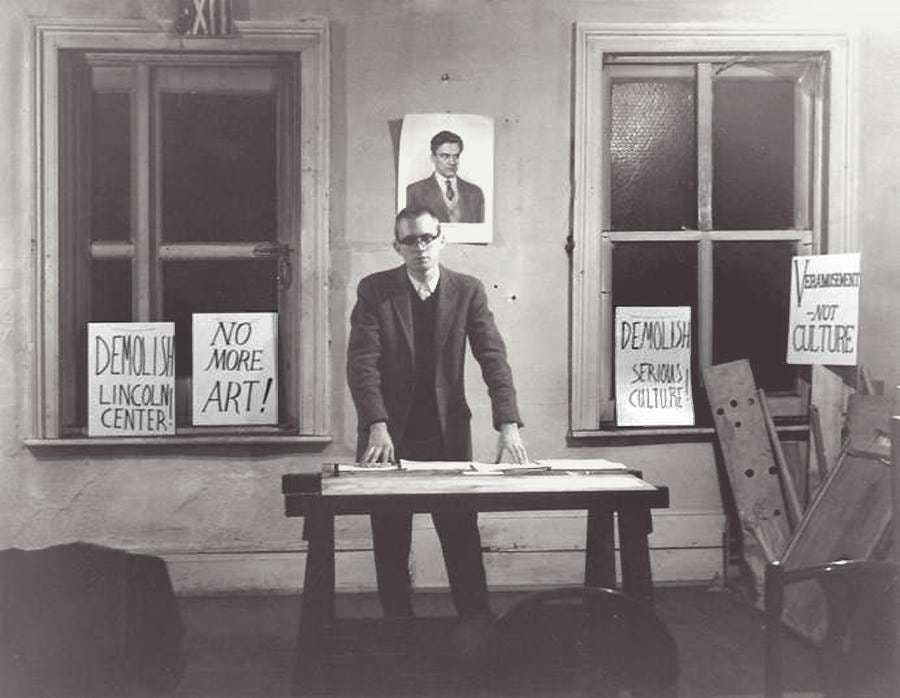

On February 27, 1963, with his Harvard friend Tony Conrad and filmmaker Jack Smith, Flynt demonstrated against cultural institutions in New York City and marched with placards outside of the Museum of Modern Art, the Philharmonic Hall at Lincoln Center, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (where the Mona Lisa was then being exhibited to record numbers of visitors). They carried signs bearing the slogans: “Demolish Serious Culture!”; “Destroy Art!”; and “Demolish Art museums!”

The following evening at world-renowned American minimalist sculptor and composer Walter De Maria’s loft, Flynt delivered the lecture titled “From ‘Culture’ to Veramusement,” adapting and inventing the term “Veramusement” from the Latin “veritas” and the English “amusement.” The term signified the truth of enjoyment in personal kinds of pleasure or pure recreation. The audience entered the room by stepping on a print of the Mona Lisa used as a doormat. While he stood before a large picture of the Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, Flynt railed about the human “suffering caused by serious-cultural snobbery by its attempts to force individuals in line with things supposed to have objective validity, but actually representing only alien subjective tastes sanctioned by tradition.”

Flynt wanted avant-garde art to be superseded by his term Veramusement, which he associated with pure instinctual recreation or art as an act of play pursued for its own sake outside of economic and market forces. He called for activities done without any consciousness of authorship, without any outside social or financial demand, free of competition, and therefore considered, once completed, not art but Veramusement.

Flynt was especially alienated by the aura of celebrity surrounding Karlheinz Stockhausen and organized a legendary protest against the German composer on April 29, 1964. Calling themselves “Action Against Cultural Imperialism,” Flynt, along with Tony Conrad and Jack Smith, picketed against Stockhausen’s musical form of what Flynt called “Serious Culture.”

Flynt later re-named Veramusement as “Brend,” a neologism which stood for a utopian aesthetic of pure subjective enjoyment, unrestrained by convention, objective standards, or subjective value. In Flynt’s words: “You just like it as you do it… These doings should be referred to as your just likings. These just-likings are your Brend.

Brend required the cultivation of one’s individual idiosyncrasies and preferences, which he defined as a “contentless model” for arriving at one’s “aesthetic self” by-passing socially inscribed pseudo-culture, or “pseudo-brend” and reaching a point where one’s own individual “just-likings” could be found.

I have to admit, I admire his thinking on the subject. Although it may be a stretch on a practical level, I agree with him in theory. This idea that I just like things as I do appeals to me. In fact, it’s a theory that I have applied to music my whole life and defines my journey on that Big River called Jazz.

In the world of experimental music in the United States, Henry Flynt occupies a unique place in history.

His efforts as a composer began in earnst in 1961 with efforts in the direction of, in his own words, “out-moderning modern and out-Cageing Cage”. However, he soon turned sharply away from classical and new music after hearing John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Don Cherry. It was through Ornette that he learned that he didn’t have to play a piece as written perfectly, as with classical music. He discovered a newfound freedom in music that inspired him, saying:

I guess that’s what turned me around. I just underwent a total conversion as a result of hearing that. And I immediately decided that the best musicians in the United States were at the bottom of the social ladder. The rest of the time I spent with music I spent working out the implications of that. I was trying to translate La Monte’s aesthetic principles into basic Country.

At the same time that he found that Country Blues existed, he was moving left towards Marxism. By early 1963, he was affiliated with the New York Workers World Party. In a 2004 interview with The Wire magazine, he told Kareem Black:

The Communist party of the US had adapted the Woody Guthrie aesthetic as their official position. The Soviet Union was extremely happy with Paul Robeson and his so-called singing the Russian folksongs, and I thought that was an unmitigated disaster. I was horrified. They were not even drawing musically on the originality, the creativity, of the people that they claimed to be standing for. It’s even more ironic because Woody Guthrie did a hillbilly radio program in LA. I find that very curious because the man didn’t have a hillybilly note in his repertoire. They’re European nursery songs. That’s his aesthetic.

He eventually became disenchanted with Marxism, left the Workers World Party in 1967, and enrolled in NYU to pursue a degree in economics; however, he remained highly critical of established institutions of “serious culture,” Flynt began in the 1960s to radically reconfigure Southern music by combining blues licks and country fiddling styles with a modal approach to extended improvisation.

He embodied this view on music at the end of 1963 with new ethnically-based recordings that would not be released until nearly 40 years later as the two-volume set Back Porch Hillbilly Blues. From that session, he recorded his first unaccompanied acoustic violin piece, Acoustic Hillibilly Jive, which you can hear at the 6:16 minute mark of this video:

The video includes both volumes of Flynt’s Back Porch Hillbilly Blues, released in 2002 on the Chicago-based Locust Music label.

Flynt soon moved to the electric violin, but I prefer songs from this session that feature guitar work, like Blue Sky, Highway, And Thyme:

In the mid-1960s, Flynt rubbed elbows with the circle that would eventually become the Velvet Underground and took some guitar lessons from Lou Reed. In September 1966, Flynt played violin with The Velvet Underground as a stand-in for John Cale for two weekends (four days) at The Dom in the East Village. The notice in the Village Voice, 29 September 1966, referred to "the screeching electric violin."

His collaboration with Reed led to the formation of Flynt’s garage punk protest music band called the Insurrections, which featured Walter De Maria, who became the drummer in the New York-based rock group the Primitives, the precursor to The Velvet Underground. In 1966, Flynt’s band recorded Uncle Sam Blues from the I Don’t Wanna album, released by Locust Music in 2004:

The music on I Don’t Wanna was Flynt’s way of telling the music industry, in his words:

I did the Insurrections material, telling these people, ‘This is what you should be doing, you shouldn’t be going with Woody Guthrie stuff. It’s idiotic.’

In 1968, Flynt recorded with Angus MacLise on a song called Dreamweapon Benefit For The Oklahoma City Police Dept., which was released in 2000 by the Siltbreeze label as Brain Damage In Oklahoma City. Flynt plays flute and adds voice:

This improvised dronework is performed by a group that included, along with Flynt, MacLise on congas, his wife Hetty MacLise on tambura, Jackson MacLow on recorder and voice, and Tony Conrad on strings. The track was recorded following MacLise’s 1968 arrest for drug possession in Oklahoma. Interestingly, this recording predates MacLise’s 1970 Asia tour that ended with their settling in Kathmandu, Nepal. In Kathmandu, MacLise helped operate the Spirit Catcher Bookshop, which became a gathering place for the growing community of artists and poet expatriates living and working in the area. Along with Beat poet and photographer Ira Cohen, MacLise helped found Bardo Matrix Press in Kathmandu, which I wrote about here.

In the early months of 1975, in an attempt to further radically reconfigure Southern music, Flynt headed the country rock band Nova’Billy, devoted to his compositions like I was a Creep:

…and Left Ear (Greensboro Senior High Song):

According to Flynt in his 2004 interview with Black:

I was really transferring the techniques that I picked in the whole modern music thing. I was just transferring them to rock.

However, at about this time, punk also hit the scene, and many of his bandmates abandoned him for punk groups. That was the end of the line for this new project. Flynt recalled:

There was no way people were ready for it. It fell flat on its face. I picked a particular moment when I got slammed by the punk invasion from Britain and at least two of the musicians I was working with sort of ‘defected’ to punk. But even if there had not been that problem, the problem is that…what the audience wants is oblivion. They want an entertainment experience equivalent to hitting their head with a mallet or hitting a bottle of booze. In that sense it was just the wrong moment for me. I actually hope that for what I am doing now, enough time has passed that it will be more possible.

After Nova’Billy, Flynt returned to a mellower, groove-oriented ensemble performance of what he called “contemporary cowboy raga,” and from 1975 to 1979, recorded Gradation and Other New Country and Blues Music. Here is his song Graduation:

Gradation and Other New Country and Blues Music was originally planned to be released in 1980, but things never came together until 2001, when it was first released on the Ampersand label.

It’s important to remember that Flynt’s first commercial release wouldn’t be until 1986, a quarter of a century after his performance in the La Monte Young–curated series at Yoko Ono’s loft. That release was of two songs, You Are My Everlovin’ and Celestial Power, recorded in 1980 and 1981 for Edition Hundertmark, a German Gallery and editor of music from the Fluxus movement. A cassette was released in 1986:

I already featured You Are My Everlovin above. Here is the flip side of the cassette, Celestial Power:

In 1983 in Woodstock, New York, Flynt collaborated with Swedish musician, poet, philosopher, mathematician, and visual artist Catherine Christer Hennix on the album Dharma/Warriors, released in 2008 on the Locust Music label. From the album, here is Warriors of the Dharma:

The song was based on a repeated C chord in a rock format, suggested to him by Walter De Maria.

Produced between 1963 and 1984, all these works provide a wonderful opportunity to reexamine the history of U.S. experimental music from the critical perspective of an iconoclastic intellectual. However, it may be misleading to persist in describing Flynt as a violinist and composer, as by his own account, he had given up performing music in 1984.

It’s tempting to declare Henry Flynt simply a crackpot. However, many celebrated artists and intellectuals throughout history would be subject to similar charges. His decision to completely abandon modernism in favor of the music of working-class poor Americans, challenging the revolutionary bona fides of his avant-garde peers and the very legitimacy of high culture as an institution, does have merit.

Flynt was advocating for a different kind of freedom: freedom from imperialism and from what he identified as elitist cultural institutions. Moreover, he maintained that this commitment to liberation could not originate from a European high-art perspective, arguing that the authority complex of “serious culture” was integral to global systems of domination.

In “The Meaning Of My Avant-Garde Hillbilly Music,” he writes, “I was competing with musicians for whom the last step in composing a piece is the sale - musicians for whom a bad piece that sells is a good piece.”

In 1994, in his essay AGAINST "PARTICIPATION": A Total Critique of Culture, Flynt wrote:

The conclusion of my theory is that all art embodies the lie of the advertiser who says "wear my clothes to be yourself."

Brend is every doing of an individual which is not naturally physiologically necessary (or harmful), is not for the satisfaction of a social demand, is not a means, does not involve competition; is done entirely because the individual just likes it in doing it, without any consciousness that anything is not-originated-by-self; and is not special exertion. (And is done and "then" turns out to be in the category of "brend."

Flynt’s emphasis on analyzing the subjective development of the creep personality and the necessity of developing one’s individual “Brend” to counter “Serious Culture” and the impact of imperialist European aesthetics has merit. His theory to affirm personal “just-likings,” while at the same time allowing for a whole range of differences, namely, individuals’ complementary and conflicting values of expressive “just-likings” and practices, was ahead of its time. I think it also had merit.

I think it’s unfortunate that the work of Henry Flynt exists in its own orbit, forever on the fringe and over the edge of mainstream sensibility. Nonetheless, I admire Flynt’s anti-art conviction. In the end, his idea of blowing harder against mass commercialism appeals to me. And although I walk to the edge, I think I still gravitate toward Cornelius Cardew’s position, as he wrote on a postcard to Flynt dated June 7, 1963:

Dear Mr. Flynt…Since I may be depending on organized culture for my loot & livelihood I can wish you only a limited success in your movement.

Perhaps Flynt himself finally did come around to Cardew’s perspective. Since 2007, he has been involved in releasing dozens of CDs of his recorded but unreleased musical compositions. I suspect it may have been done for a little loot and livelihood. And so it goes…

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of Oliver Lake.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….