Helen Forrest

From out of nowhere and back...

The most dramatic moments of my life were crammed into a couple of years from the fall of 1941 to the end of 1943. They seem to symbolize my life...that was when the music of the dance bands was the most popular music in the country, and I was the most popular female band singer in the country, and Harry [James] had the most popular band in the country. It didn’t last long, but it sure was something while it lasted. Everyone should have something like it at least once in their lives. I’m grateful I did.

-Helen Forrest

A few weeks ago, I was looking through old 78 rpm records at Dusty Groove in Chicago and came across this Decca record:

The song is from You Came Along, a 1945 Paramount film set in World War II. Surprisingly, the screenplay was written by Ayn Rand a couple of years after she published her novel The Fountainhead.

The vocalist on that record is Helen Forrest, performing with the Victor Young Orchestra:

The song had previously appeared as You Came Along, Out of Nowhere in the 1931 Paramount western Dude Ranch. However, for the 1945 You Came Along, the lyrics were changed to “From” Out of Nowhere.

If you go to the 49.20 minute mark of this video, you can also watch Helen Forrest sing a little bit of From Out of Nowhere in the 1945 film:

When I found the record, I knew who Helen Forrest was, but I had never heard her music or known about her background. But I did like the song, which I first heard as a kid back in the 1970s, while watching the 1960 film The World of Suzie Wong on TV. Here’s that swinging version:

When Helen Forrest recorded From Out Of Nowhere in 1945, she was only 25 years old; however, by that time, she had left Harry James’ band two years earlier and already worked with both Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman.

When she joined Harry James’ band in 1941, she broke new ground for American vocalists. She asked that specific arrangements be written just for her and that the band accompany her lead vocal rather than the other way around, which was the norm in those days. Harry James agreed, and Forrest went on to record five gold records with him: But Not for Me, I Don’t Want to Walk Without You, I Cried For You, I’ve Heard That Song Before, and I Had the Craziest Dream.

This week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig in our paddles and explore the world of Helen Forrest.

Helen Forrest was born Helen Fogel on April 12, 1918, in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Helen’s mother met and married a housepainter by the name of Feigenbaum. She recalled that her parents often asked her not to come home right away after school. As she got older, she began to realize that during the day, her home was a brothel. As Helen matured physically, her stepfather tried to accost her sexually. She told her mother of his attempts, but Rebecca Fogel did not believe her daughter. When Helen was about fourteen, her stepfather trapped her in the kitchen, and she defended herself with a kitchen knife. As a result, she moved out and went to live with her piano teacher, Honey Silverman, and Silverman’s family.

Helen later decided that she wanted to be a singer and left for New York City, where she visited song publishers and auditioned at a local radio show. During one of the radio spots, as the story goes, a sax player thought that the name Fogel was “too Jewish,” and therefore Helen Fogel changed her name to Helen Forrest. In 1934, at seventeen years of age, Forrest got her first job singing commercials at WNEW in New York.

After seeing Forrest at the Madrillon nightclub in Washington, D.C., Artie Shaw asked her to go on tour with him. Shaw was looking for new talent when vocalist Billie Holiday decided to leave the band during a lengthy stay at the Roseland-State Ballroom in Boston. So in 1938, Shaw brought in another female singer, CBS’s Bonnie Blue, who really was Helen Forrest. For a while, Holiday and Forrest shared the bandstand.

Here is one of my favorite Forrest songs, performed in 1938 with the Artie Shaw orchestra, A Room With A View:

And here is another Forrest classic from 1939, totally holding her own on the song Billie Holiday made famous, Any Old Time:

Finally, still with the Shaw band, released in 1940, here is All The Things You Are:

I wrote about the fine Hammerstein and Kern song All The Things You Are here:

Helen Forrest became a big star in Shaw’s band, but in late 1939, she left after Shaw dissolved the band for personal reasons.

Some say that two of the best things that ever happened to Benny Goodman took place in 1939. One was the addition of Red Norvo’s Eddie Sauter to his arranging staff; the other was hiring Forrest in December. Forrest may well have been the best of all Goodman’s vocalists.

Here is Forrest singing with the Benny Goodman orchestra to a Sauter arrangement of the Gershwin song The Man I Love, recorded on November 13, 1940:

Interestingly, the record was not released until 1945. I’m not sure of the reason for the delay.

Also in November 1940, Forrest recorded Taking A Chance on Love, this time with a terrific arrangement by Fletcher Henderson:

When Vincente Minnelli’s 1943 film version of the 1940 play “Cabin In The Sky” premiered in early spring, moviegoers were especially attracted to this catchy number, performed on-screen by Ethel Waters. In the wake of the film, Forrest’s 1940 version of Taking A Chance on Love was reissued and became one of two major hits by Goodman that year. The other was Why Don’t You Do Right with Peggy Lee, the main vocalist for his band in 1943, since Forrest left Goodman in August 1941.

In 1941, Forrest approached Harry James, offering to work for him under one condition: that she be permitted to sing more than one chorus. Although James was looking for a more jazz-oriented singer, he allowed Forrest to audition. The band voted her in, and she was hired.

In a 1994 interview, Forrest shared:

Harry James was wonderful. When I joined him, I said, “There’s only one condition: I don’t care how much you pay me, I don’t care about arrangements. The one thing I want is to start a chorus and finish it. I want to do verses, so don’t put me up for a chorus in the middle of an instrumental.” He said, “You got it,” and that was it.

She also shared:

I’ve got to thank Harry for letting me really develop even further as a singer. I’ll always remain grateful to Artie and Benny. But they had been featuring me more like they did a member of the band, almost like another soloist. Harry, though, gave me the right sort of arrangements and setting that fit a singer. It wasn’t just a matter of getting up, singing a chorus, and sitting down again.

Forrest would go on to record three #1 hits with the Harry James Orchestra.

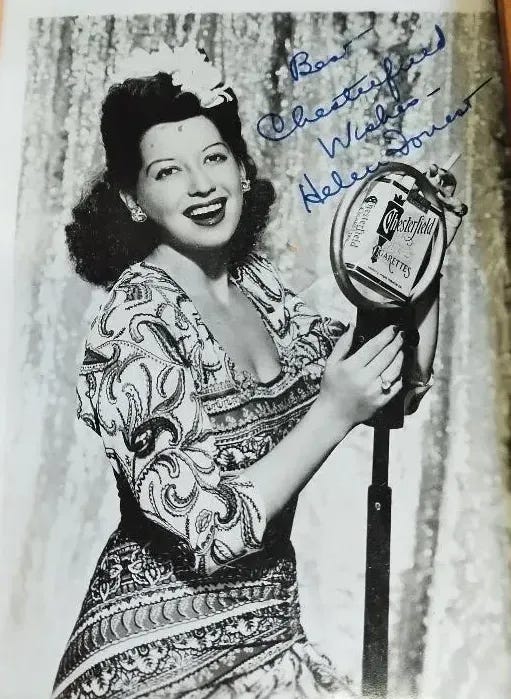

By early 1942, James began seeing one success follow another at an ever-quickening pace. He achieved his biggest success in the autumn of that year when he took over for Glenn Miller as the band featured on the CBS Chesterfield radio show. The popular show presented him, the band, and Helen Forrest three times a week. I love this photo with the Chesterfield Microphone, signed by Forrest, “Best Chesterfield Wishes.” Old school:

Here’s one of Forrest’s three #1 hits, I’ve Heard That Song Before, recorded by Harry James and His Orchestra on July 31, 1942, the last day of recording before the Musicians Union’s ban. It was released by Columbia Records on December 4, 1942:

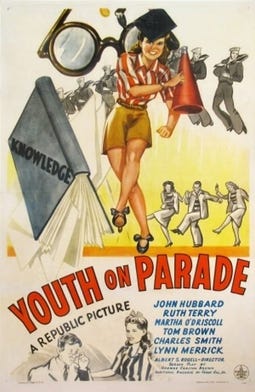

Although the most notable version of the song was this James and Forrest version, I’ve Heard That Song Before was composed with music by Jule Styne and lyrics by Sammy Cahn for the 1942 Republic Pictures film Youth on Parade:

Even though Republic was a “poverty row” Hollywood film studio, the song was nominated for the 1942 Academy Award for best original song; however, it lost, not surprisingly, to Irving Berlin’s White Christmas.

However, when Styne was paired with Cahn for the 1942 Youth on Parade, Styne considered Cahn to be a step down. He also told friends and wrote in his autobiography that Cahn possessed no musical education and didn’t play an instrument. After the film, they split up, but then, after I’ve Heard That Song Before hit number one on the charts, they got back together to write some more songs.

They went on to write a series of romantic ballads that Frank Sinatra made famous, like It’s the Same Old Dream, Give Me Five Minutes More, Saturday Night Is the Loneliest Night of the Week, and the Christmas favorite Let It Snow.

Cahn once described how he and Styne wrote Let It Snow:

It was one of the hottest days in the history of Los Angeles. I asked Jule “Why don’t we drive to the beach to cool off?” He said “Why don’t we stay here and write a winter song?” We imagined a man and a woman cozy by the fire, eating popcorn, staring out the window, watching the snowflakes fall, and thinking, “Let it Snow! Let it Snow! Let it Snow!”

In 1947, they also wrote It’s Magic for Doris Day in her Warner Bros. film debut, Romance on the High Seas. It became a huge hit.

Here’s a great version by Sarah Vaughan:

Although Time After Time was written for Frank Sinatra to introduce the 1947 MGM film It Happened in Brooklyn, the first recording of it was Vaughan’s version with the Teddy Wilson Quartet on November 19, 1946, for the Musicraft label. However, my favorite version was recorded by Chet Baker in 1956 for the Pacific Jazz label with Russ Freeman on piano, Carson Smith on bass, and Bob Neel on drums:

Here’s a wonderful video of Baker performing the song live eight years later in Belgium:

It doesn’t get any better than that.

It was hits like these that kept Styne and Cahn at the top of their profession during the postwar years. However, their time together was short-lived, beginning in 1942 and lasting less than a decade. They did, however, remain friends and collaborated many years later on the musical Look to the Lilies in 1970.

In 1942 and 1943, Helen Forrest was voted the best female vocalist in both the Down Beat and Metronome polls. At the top of her game, Forrest left Harry James in late 1943 to pursue a solo career, saying, “Three years with a band is enough.”

In the latter half of the 1940s and the 1950s, Forrest headlined at theaters and clubs. She did make some top ten records along the way, mostly with Dick Haymes, and in 1955, joined Harry James again in the studio to record a swing album called Harry James in Hi-Fi, which became a bestseller. During the 1970s and 1980s, she performed in supper clubs and on “big band nostalgia” tours, including appearances with Harry James and Dick Haymes. In 1982, her autobiography, I Had the Craziest Dream, was published and is dedicated to her only son. In 1983, she released her final album, Now and Forever. From that album, here is another version of the Styne and Cahn tune I’ve Heard That Song Before, recorded in New York with an all-star band which included the great Hank Jones on piano, Frank Wess on sax, Bob Zottola on trumpet, Grady Tate on drums, and George Duvivier on bass:

She continued singing until the early 1990s, until rheumatoid arthritis affected her vocal chords and forced her to retire.

Here’s one more for the road. In May 1940, Fred Astaire recorded two sides with the Benny Goodman Sextet in Los Angeles. Astaire sings and tap dances on the song he wrote with lyrics by Gladys Shelley, It’s Like Taking Candy From A Baby, arranged by Fletcher Henderson:

Also, note that on the label, Astaire’s tap dancing is called “Actual Step Dancing.” Funny - I’m not sure what that is. The song also included Lionel Hampton on vibes and Charlie Christian strumming his guitar in the background, too

Anyway, this was a nice session. Astaire sings on two tracks, Forrest sings with Goodman’s orchestra on the other three. Here’s a rarely heard song that I like a lot, Mister Meadowlark, with the music composed by Walter Donaldson and lyrics by Johnny Mercer:

“Mr. Meadowlark, meet me in the dark tonight.” Nice. This is a fun song with some nice solos by Ziggy Elman and Benny Goodman.

Helen Forrest passed away on July 11, 1999. She was 82 years old. She was laid to rest at Mount Sinai Memorial Park Cemetery in the Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles.

Like the careers of Styne and Cahn, nothing was the same for Helen Forrest after the 1940s. This is a good reminder that fame can be fleeting. In some regards, my journey From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra is a chance to remember the great musicians and artists of old. Napoleon Bonaparte said, “Glory is fleeting, but obscurity is forever.” Not if we take the time to look back and remember…

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the world of one of my favorite Fred Astaire movies, the surrealistic fantasy Yolanda and the Thief.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….