We must first realize that dancing is an absolutely independent art, not merely a secondary accompanying one. I believe that it is one of the great arts.

-George Balanchine

In many ways, my jazz journey grew from my early love of movies, mostly old musicals and in particular the movies of Fred Astaire, who drew me into the world of dance.

As a boy, when I saw him dance for the first time on TV, it was like a door had opened - an invitation to the dance. For a moment I stood before the door, it was a reckoning.

Once I decided to walk through the door, it began as a dream.

I started tap dancing in seventh grade and continued throughout high school. All the practicing and performing culminated in winning the 1980 Minnesota State Tap Dance Solo Championship. Then, after I graduated, I hung up my tap shoes and joined the military. To this day, over 40 years later, I’ve only had on my tap shoes for one occasion, but that’s a story for another time…

As I look back on those days now, a half-century later, I am reminded of what Theodor Herzl wrote:

All activity of men begins as a dream and later becomes dream once more.

When I got out of the service, after living in Carmel, California for a couple of years, I moved to Silicon Valley to find a job. I lived in Campbell for a few months until I rented an apartment in Cupertino. I spent a lot of time in Palo Alto, which was about a 15-minute drive from my place. I was boringly predictable and went to the same three places: Bell’s Book Store, Tower Records (long gone now), and the Stanford Theatre.

After the death of Fred Astaire in 1987, the son of Hewlett-Packard co-founder David Packard, David Woodley Packard put on a film festival of Astaire's works at the Stanford Theatre. The two-week festival was so successful that his father agreed with Woodley Packard's idea to purchase the aging theatre for $7.7 million and restore it at an additional cost of $6 million. The Stanford Theatre showed The Wizard of Oz at its 1989 grand reopening.

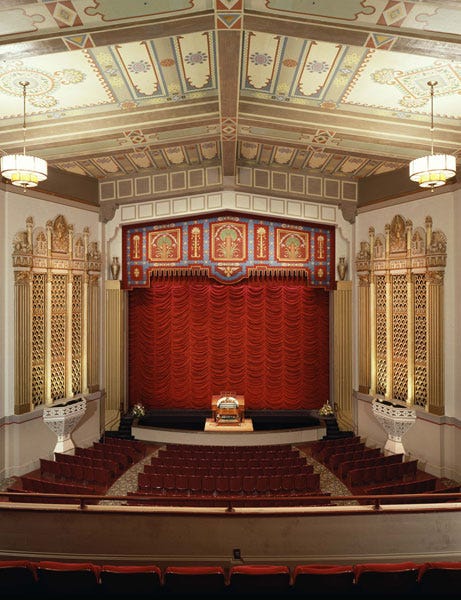

Located in the heart of Palo Alto on University Avenue, the Stanford Theatre is an absolute gem:

It was on the big screen there that I rekindled my love of old movies. I still have the program from the first movie I saw there during a Greta Garbo Festival in April 1990.

I can’t recall for sure, but I think it was at the Stanford Theatre during a Gene Kelly Festival that I saw Invitation to the Dance, Kelly’s 1956 debut as a director. He also choreographed the dance sequences:

Invitation to the Dance was unlike any movie I had seen before in that it had no spoken dialogue, with the characters performing their roles entirely through dance and mime. The film is a dance anthology consisting of three unrelated stories. I was immediately captivated by the film, particularly the first story, which features two leading dancers of the era: Igor Youskevitch and Tamara Toumanova. Both had earlier in their careers danced to ballets choreographed by ballet master George Balanchine.

In the first story, Igor Youskevitch dances in a wonderful performance with the most famous postwar French ballerina Claire Sombert:

In the second story, Kelly dances with Russian-born prima ballerina Toumanova:

In 1931, when Toumanova was 12 years old, Balanchine saw her in ballet class and invited her to the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, along with Irina Baronova (aged 12) and Tatiana Riabouchinska (aged 14). The three girls were an immediate success, and writer Arnold Haskell dubbed them the "baby ballerinas". When Balanchine was eventually fired from Les Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo, he and Toumanova moved to New York City to start a distinctively American ballet.

This week on that Big River called Jazz we’ll dig in our paddles and explore the world of George Balanchine.

George Balanchine was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, in January of 1904, and studied standards and technique at the Imperial Ballet School.

He left Russia during the revolution and settled in Germany, where Serge Diaghilev invited him to join the Ballets Russes troupe, which revitalized ballet and energized Paris in the first decades of the twentieth century.

In the same way that Wagner tried to unite all the arts in his grand opera, Diaghilev tried to unite all the arts in his ballet - a combined impact of music, decor, and dancing. Diaghilev would weave these various art forms into a cohesive and aesthetically riveting performance that captivated audiences in Paris and beyond. His company was a meeting ground for Picasso, Cocteau, and Chanel. He also commissioned Stravinsky, Debussy, Ravel, Satie, and Prokofiev to write scores.

From 1916 onwards Pablo Picasso worked with Diaghilev on six separate ballet productions, seizing the opportunity to expand his studio practice out into an entirely new arena, revealing some of the most adventurous work he would ever make. Here’s a set Picasso designed and used for Ballets Russes productions The Three-Cornered Hat in 1919 and Pulcinella in 1920:

Here’s a poster designed by Jean Cocteau:

Those years with Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes served as an invaluable apprenticeship for Balanchine. He soon became Diaghilev’s principal choreographer, and his first substantive effort was choreographing Ravel’s L’Enfant et les Sortilèges, then a reworking of Stravinsky’s Le Chant du Rossignol.

Unfortunately, the Ballet Russes’s final performance was in London at the Covent Garden Theatre on July 26, 1929, and after Diaghilev’s death on August 19, 1929, in Venice, the company closed down.

In 1931, when financier Serge Denham, René Blum, and Colonel Wassily de Basil formed Les Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo, the company hired Balanchine as a choreographer. Thanks to The Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo, Diaghilev's work was able to continue.

However, to create his own new works set to music that no one had yet choreographed, Balanchine formed Les Ballets 1933. Although the company only ran for less than four weeks. During this time Balanchine met Lincoln Kirstein, the heir to a department store fortune who had been following Les Ballets 1933 performances in Paris and London. When Balanchine was fired, Kirstein convinced him to move to New York City to start a distinctively American ballet. Toumanova left the company and joined him in New York City.

With 32 students on January 2, 1934, the School of American Ballet opened on 637 Madison Avenue in New York City. At 29 years old, Balanchine led the faculty, many Russian emigres who like him had fled the Russian Revolution: Pierre Vladimiroff, Felia Doubrovska, Anatole Oboukhoff, Hélène Dudin, Ludmilla Schollar, Antonina Tumkovsky, and Alexandra Danilova.

On October 11, 1948, when Concerto Barocco, Orpheus, and Symphony in C, were performed at the City Center of Music and Drama, the New York City Ballet was born. From that time until he died in 1983, Balanchine served as the New York City Ballet’s ballet master and chief choreographer. The ballet is now located in the Koch Theatre at Lincoln Center:

The New York City Ballet will perform All Balanchine I and All Balanchine II this season to showcase Balanchine’s multifaceted talent.

It was Diaghilev’s influence that helped Balanchine revolutionize the way dance was taught in America. With the founding of his school and company, Balanchine changed the style and look of ballet and opened the eyes and ears of audiences to the marriage of music and dance. Balanchine’s focus on a streamlined and clarified classical style revolutionized dance and is still taught today. In his book Diaghilev’s Empire, Rupert Christiansen wrote:

Balanchine’s love for the New World burgeoned - he was particularly fascinated by… the breezy energy of the drum majorette and embraced the razzmatazz of Broadway and Hollywood. It would be a slow, uncertain start, but the field was wide open and another major chapter in the history of ballet had begun.

In 1941, Tanaquil Le Clercq won a scholarship to the School of American Ballet. She was considered Balanchine's first ballerina. She was trained in his style from childhood and became one of his most important muses. During Le Clercq's tenure with the company, Balanchine, Jerome Robbins, and Merce Cunningham all created roles for her.

At the age of nineteen, Le Clercq became a principal dancer with the New York City Ballet and became one of the great ballerinas of the 20th century:

In 1946, when Le Clercq was fifteen years old and one of the brightest lights at Balanchine’s School of American Ballet, he asked her to perform with him the role of a girl with polio in Resurgence, a dance he choreographed for a March of Dimes charity benefit at the Waldorf-Astoria.

Balanchine played a character named Threat of Polio, and Le Clercq was his victim. The music was Mozart’s String Quintet in G minor, and at the close of the plangent adagio, Balanchine came onstage wearing a large black cape and enveloped her. She became paralyzed and sank to the floor. In the final movement — a sunny allegro — she reappeared in a wheelchair. Then children tossed dimes at her character, prompting her to get up and dance again.

In a strange twist of fate, ten years later in 1956 on the New York City Ballet’s European tour in Copenhagen, Le Clercq’s dancing career ended abruptly when she was stricken with polio. She did eventually regain most of the use of her arms and torso but remained paralyzed from the waist down for the rest of her life. I wrote about this and the role dance plays in human development here:

Filmed in October 1955 just months before her tragedy, here’s a wonderful Canadian video of Le Clercq dancing with Jacques d'Amboise to Nijinsky’s Afternoon of a Faun choreographed by Jerome Robbins:

Here’s one more for the road. Balanchine worked on pieces for opera, Hollywood, Broadway, the circus, television, and British vaudeville, bringing his choreography to the wider audience he loved to entertain, successfully blurring the lines between the artistic and the commercial in dance.

This was a trend started in 1948 with Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s British film The Red Shoes, which featured the character Boris Lermontov, who was inspired in part by impresario Diaghilev:

When I first saw the film’s fifteen-minute The Ballet of Red Shoes sequence, I was reminded of the first number in Kelly’s Invitation to the Dance filmed eight years later. I’m sure it must have served as an inspiration to Kelly:

The Red Shoes marked the transition from opera, which was the most imaginative, fertile, and powerful performing art in the second half of the nineteenth century, to ballet and cinema as ushered in by Diaghilev and later Balanchine in the first half of the twentieth century. However, by the time Invitation to the Dance hit the screen, the influence of ballet was already beginning to decline.

George Balanchine died in New York on April 30, 1983. He was 79 years old. Perhaps Balanchine’s masterpieces were ballet’s last great hurrah. The post-modern aesthetic starting with Martha Graham and moving to Merce Cunningham and the Judson Dance Theater cut a new path. As Christiansen wrote, “In following this path, Judson left ballet behind, and some would say that it never quite caught up.”

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of drummer Steve Reid.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel so inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Absolutely fascinating read, thanks Tyler. As someone certified as having two left feet I find Dance as an art form captivating and intriguing. I come at it from a Graham and after perspective only because that's how I was initially exposed to it. The film of Le Clerq dancing 'Faun' is beautiful, I had no idea of her tragic story, you almost couldn't make it up.

The Toumanova / Kelly dance is seduction at the highest level - great share!