Fred Anderson

Lone Prophet of the Prairie...

The Velvet’s owner, primary barkeep, and sometimes headlining act, tenor saxophonist Fred Anderson—scene caretaker, underground booster, indefatigable cultural worker, quiet force for good.

-John Corbett

When I got out of the service in the late 1980s, I lived in Carmel, California, for a while. I worked part-time at an antique store. After a while, I decided I’d better get a full-time job and headed over to Silicon Valley to look for work.

The first job I found was working at the Marine Division of Westinghouse in Mountain View, near San Jose. I planned launch tubes for the Department of Defense’s ICBM railcar launch systems. I worked there for a while, but it was a little too much like the army, so I took a job working with some Stanford engineers who were working on developing lithium rechargeable batteries - this was in the early 1990s. That didn’t work out too well, as their main business was in the lead-acid and nickel-cadmium battery space, and they moved manufacturing down to a Maquiladora in Tijuana. So I found a job working in a small, family-owned company that made hematology equipment. I loved that job. We worked hard and played hard.

It was mostly during that time, while working at Wessex Book Store in Menlo Park, that I dug deep into jazz. I worked Friday nights after work and early Saturday afternoons with my friend Luis, who was a professor at De Anza or Foothill College. We always played jazz on the store’s record/CD player. I remember playing my first Sun Ra album for him. He liked it, and we became big Sun Ra fans, searching for and collecting all we could find. Then, Abbott Labs bought the company I worked for, and I got transferred to their headquarters in North Chicago, Illinois. That was a big moment in my life. I was going to Chicago.

I knew nothing about Chicago. Zero, except their sports teams, like the Bears, Blackhawks, and Cubs. I grew up mostly in Minnesota, so I was a Midwesterner, which was about as close as I came to Chicago, the city on the make, as Nelson Algren called it. He wrote:

A town with a nervous violence of a two-timing bridegroom. Where bulls and foxes live well, but lambs wind up head-down from the hook. A city that divides your heart, leaving you loving the joint for keeps, knowing it can never love you.

Algren dedicated his 1951 book, Chicago: City on the Make, to Carl Sandburg, who was from Galesburg, Illinois. Sandburg moved to Chicago in 1912 after living in Milwaukee, and in 1916 wrote Chicago Poems.

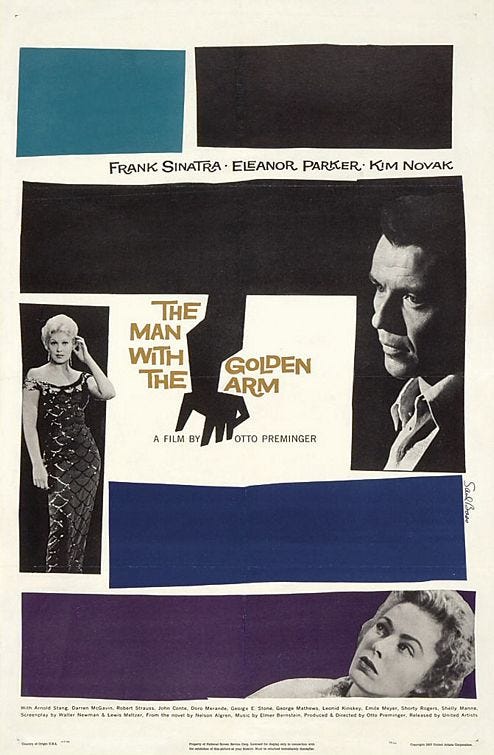

I had read Nelson Algren’s book The Man with the Golden Arm and seen Frank Sinatra play Frankie Machine in the 1955 film noir directed by Otto Preminger:

The film’s soundtrack was scored by Elmer Bernstein and featured jazz themes performed by Shorty Rogers and his Giants. It’s not my favorite soundtrack, too brash. But it’s nice to see those guys get some exposure. Here is Shorty and the boys during the film’s audition sequence, sounding kind of Kenton-like:

Anyway, I read about a Birthday Party for Nelson Algren in downtown Chicago at a place called the Bop Shop. Now, I knew that he had passed away in the 1980s, so I decided to see what it was all about. Evidently, every year the Nelson Algren Committee celebrated the author’s birthday at some local establishment. I don’t recall the exact year, but it was probably 1992 or 1993. That year, it was at the Bop Shop.

When I got there, I was the only young person, by far. After a while, I noticed another young guy in the back. I walked up to him and struck up a conversation. His name was Ken Vandermark, and he was also a Nelson Algren fan. He’d recently moved to Chicago from Boston. After a few minutes, he told me that he had to go, and then I noticed him on the bandstand. He was playing at the birthday party.

This was Ken’s trio format with Kent Kessler on bass and Michael Zeran on drums. I’m not sure, but I think this was before he formed his DKV Trio with Hamid Drake on drums. This was most likely during the time he released Big Head Eddie in 1993 on the short-lived Platypus Records label. Anyway, Vandermark’s trio was awesome. After he finished, we talked a little bit more, and he invited me to a show at a place called the Velvet Lounge.

I went to the show, and that night he played alongside Fred Anderson, whom I had not heard of. That was the start of an amazing jazz education that lasted until I moved to Minnesota in the spring of 2000. As I look back now, the Chicago jazz scene was on fire in the mid 1990s, and centerstage was places like the Empty Bottle, the Hothouse, the Jazz Showcase, and the Velvet Lounge.

This week on that Big River called Jazz, we dig our paddles into the world of Fred Anderson.

Fred Anderson was born in Monroe, Louisiana, on March 22, 1929. When he was ten, his parents separated, and he moved to Evanston, Illinois, a northern suburb of Chicago, where he initially lived with his mother and aunt in a one-room apartment.

He started playing the tenor sax when he was 12. After many years of honing his skills, he began playing professionally in the early 1960s. In 1962, he formed a group with Billy Brimfield on trumpet, Vernon Thomas on drums, and Bill Fletcher on bass. They played experimental music based on things he had heard in Ornette Coleman’s music.

In Chicago writer and producer John Corbett’s 1994 book Extended Play, Anderson recalled:

We took the music out a little ways. On sessions, we wouldn’t play the licks that the people were used to hearing. Eddie Harris started telling people: “Man, there’s this guy in Chicago, Fred Anderson. You guys talk about yourselves playin’ out, Jack!”

As a result, Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre gave him the nickname, “Lone Prophet of the Prairie.” Anderson responded, “Ain’t that soemthin’. But it’s right. I was alone; nobody listening.”

Fred Anderson was an early and influential member of The Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), founded in 1965 in Chicago by pianist Muhal Richard Abrams, pianist Jodie Christian, drummer Steve McCall, and composer Phil Cohran.

It was within this community of musicians that Fred Anderson began recording, beginning on October 20, 1966, and then again on December 16 of that year at Sound Studios in Chicago, with a group of musicians led by Joseph Jarman. The sessions resulted in Jarman’s debut album Song For. The first track on the album was, I think, his first recorded composition, Little Fox Run:

Anderson also played on the second track of Jarman’s next album, As If It Were the Seasons, recorded on June 19, 1968, at Ter-Mar Studio in Chicago. That composition is called Song for Christopher, a memorial to pianist Christopher Gaddy, who died on March 12, 1968, at the age of 24. The song is based on incomplete notations by the pianist:

I believe these were Fred Anderson’s first two recordings - someone please correct me if I’m wrong!

In 1977, Anderson and Brimfield were invited to West Germany by Austrian conductor and composer Dieter Glawischnig. They were gone for a month, and when they returned, they didn’t have a place to live. So he rented a storefront in Evanston with a bandstand, PA system, folding chairs, and a few sofas. A place where he could practice and play, and for other musicians to come and sit in. He called it the Birdhouse. The idea was to have it pay for itself. The weekend performances would pay the rent, and during the week, he put on workshops. Unfortunately, the city made things difficult for him, and at the end of June 1978, he was forced to close it down and move out. Nonetheless, Anderson recalled, “The Birdhouse was a very positive thing, and I think everyone involved in trying to make the Birdhouse work knew that it was a beautiful endeavour.”

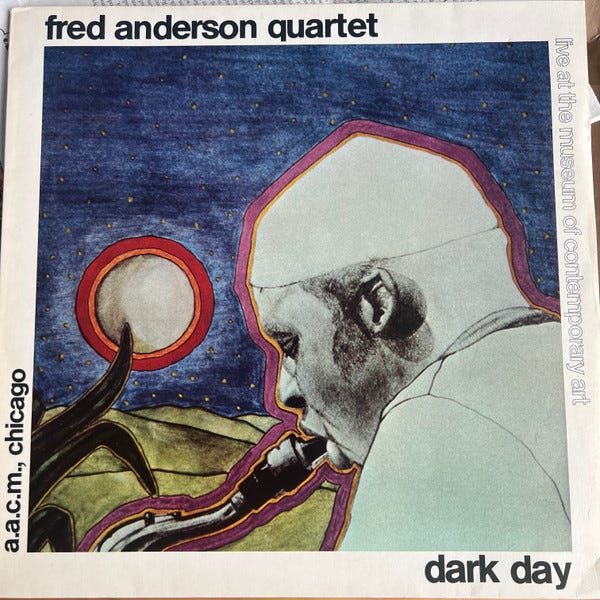

As part of a series of AACM concerts presented by the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art, on May 15, 1979, Anderson and his quartet recorded Dark Day, released in a small batch on the tiny Austrian Message Records label:

His quartet included Bill Brimfield on trumpet, Steven Palmore on bass, and “Hank” Drake on percussion. From that album, here is Drake’s composition The Prayer:

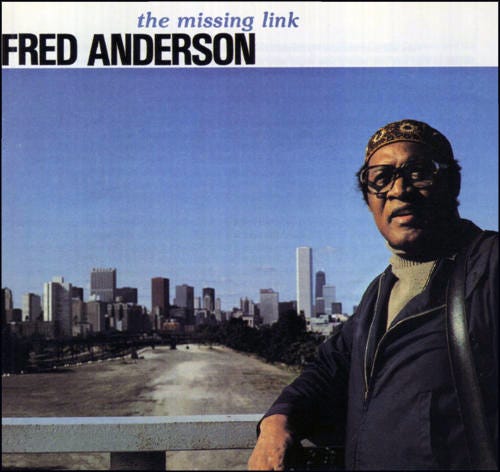

The same year, on September 17, Anderson recorded another session originally intended for release by a European label; however, the label never came through as promised, and the tapes remained dormant until many years later, when Anderson approached Chuck Nessa with a rough mix cassette and made a deal. The result was The Missing Link, which Nessa released in 1984. You can buy it here. The album caught the 50-year-old Anderson at the peak of his power and creativity. Along with Anderson at the session were bassist Larry Hayrod, drummer Hamid Drake, and percussionist Adam Rudolph.

The title of the album, The Missing Link, is a reference to the missing link between the AACM and later Chicago free jazz, a position also held by Hal Russell, whom we’ll catch up with a little further down the river.

On January 11, 1980, Anderson and percussionist Steve McCall recorded a session at Soto Studios. It was released by the Okka Disk label in 1996 as Vintage Duets: Chicago 1-11-80. The Okka Disk record label was founded in Chicago in 1994 by Bruno Johnson to document the free jazz and improvisational music scene, focusing particularly on innovative Chicago-based artists often overlooked by larger labels, and was largely responsible for Anderson’s renaissance in his later years.

Here’s a solid groove featuring Anderson, Billy Brimfield on trumpet, Larry Hayrod on bass, and Hamid Drake on drums, recorded in Milwaukee during January and February of 1980, but not released until 2000 on the Atavistic label’s Unheard Music Series, curated by John Corbett:

In 1982, undaunted by his 1977 experience with the Birdhouse, Anderson took over a local workingman’s bar called the Velvet Lounge at 2128 ½ South Indiana on the near south side and transformed it into a world-renowned center for improvised music. This was a place where guys had a chance to just get up and play. By this time, the jam session culture had nearly come to an end, and the young guns needed a place to play and express themselves freely. He told John Corbett:

I remember Von [Freeman] was playing in the 1950s with Lefty Bates, left-handed guitar player. I was practicing like mad in the fifties, but I wasn’t playing professionally. I used to go sit and listen to him. I’d just be absorbing things. One day he had a chance to hear me. He told me, “Keep on working on what you’re on, man!” One thing about Von, he encouraged me, never did discourage me. Always has something positive to say, whether he meant it or not.”

This was the attitude Anderson nurtured in a younger generation of players who came to the Chicago scene, like trombonist George Lewis, multi-reedist Douglas Ewart, and Ken Vandermark. When they came to Chicago, they asked to play with him. Anderson told Corbett, “You try to be an extension and some kind of contribution.” Just like Von Freeman had been to him.

As it turned out, the younger musicians were listening to Fred Anderson, and so was Bruno Johnson at Okka Disk, whose first release was the debut of Vandermark’s group Caffeine, released in 1995. This album represents the sound of a defiantly individual ensemble made up of defiant individuals. Caffeine was an outstanding group, and I was fortunate to have seen them many times during the vibrant jazz scene of early 1990s Chicago.

Incidentally, Okka Disk’s second and third releases featured two defiant individualist European musicians who had come across the pond to check out the Chicago jazz scene: Peter Brötzmann’s The Dried Rat-Dog, a duo album with percussionist Hamid Drake; and Mats Gustaffson’s Parrot Fish Eye, a collection of duets and trios. Both were released in 1995.

Although Anderson remained an underrecognized player during the 1980s, he recorded and performed more actively in the 1990s. The first time I met and heard Fred Anderson play was when, after Nelson Algren’s Birthday Party, Ken Vandermark invited me down to the Velvet Lounge for his gig.

The next time was when Anderson played with Marilyn Crispell at The Women of New Music Festival at the HotHouse on Milwaukee Avenue in Chicago on April 8, 1994, a trio performance with Crispell accompanied by Anderson on tenor and Drake on drums. The album from that concert was called Destiny, released by Okka Disk in 1996:

Although I wasn’t in Chicago during the 1980s, having not arrived on the scene until about 1992 or 1993, in my mind, the early 1990s signaled the beginning of an amazing era in Chicago improvisational and experimental music, with gigs at the Velvet Lounge and Lounge Ax with the Vandermark Quartet, that first meeting of Anderson and Marilyn Crispell at HotHouse, and the 1995 event called FMP meets AACM, when a group of FMP musicians joined AACM musicians in a program designed to forge and test musical alliances through a series of spontaneous exchanges similar to those at the first Total Music Meeting in Berlin 30 years earlier. It was a jazz scene that rivaled New York City in its heyday.

Then, in 1996, when John Corbett and Vandermark hosted the Wednesday night Jazz & Improvised Music series at the Empty Bottle, a flame was ignited that could be seen around the world. This series established a beachhead for European improvisers that continues today, even with the current totally messed-up visa situation.

Also in 1996, Corbett and Vandermark curated the seminal Empty Bottle Festival of Jazz & Improvised Music, which marked Chicago’s rise as a creative music hub with significant international acts, notably featuring the start of Peter Brötzmann’s Chicago Tentet, which formed at the Empty Bottle in 1997, a concert I was lucky enough to attend.

Peter Brötzmann’s Chicago Tentet included Swedish saxophonist Mats Gustafsson, whom I wrote about here. Gustafsson and Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore tore it up one festival night at the Empty Bottle with Hit the Wall (Forever):

The festival was a huge success and continued annually until 2005. About the series, Vandermark remarked:

One outgrowth of the series was that it encouraged more improvising musicians to do their own programming at other venues. Players younger than me — like Dave Rempis, Mike Reed, Josh Berman and Tim Daisy — started their own weekly series at venues like Elastic, the Hungry Brain and the Nervous Center. That curatorial attitude, which started with the AACM, has carried over to young musicians currently working in Chicago… This helped create the strongest infrastructure for the improvised music scene since I moved to Chicago in the autumn of 1989. Instead of a couple of gigs a month, which was the case when I arrived, Chicago had at least one concert happening almost every day of the week, almost always organized by musicians, a circumstance that continues to this day.

On October 31, 2025, Corbett Vs Dempsey released the epic 6-CD box set The Bottle Tapes: Selections from the Empty Bottle Jazz & Improvised Music Series, 1996-2005. You can buy the box here. This is an excellent way to listen and learn about that wonderful time in Chicago.

It’s interesting to me that neither Corbett nor Vandermark came from Chicago; both arrived from the East Coast. However, they did not merely occupy the city. Their dedication to Chicago reflects a connection, on an international scale, that transpired locally. They followed the lead of Fred Anderson and chose to invest their time and effort proving their love not only for Chicago, but for the city’s art.

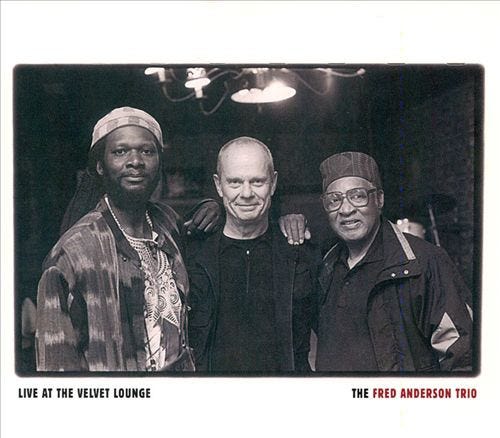

Here’s one more for the road. One of the highlights of the European/US union created during the 1990s was a June 1998 performance at the Velvet Lounge, documented by the Okka Disk label on Live at the Velvet Lounge. The album featured the stellar trio of German free jazz bassist Peter Kowald, saxophonist Fred Anderson, and his long-time collaborator, drummer Hamid Drake. You can buy it here:

From the album, here is For Those Who Know:

A decade later, on the opening night of a five-day celebration of Anderson’s 80th birthday, on March 18, 2009, Henry Grimes and Richard Davis performed at the Velvet Lounge in a tribute to Fred Anderson. The first set that night included a duo with Willie Pickens and superb bassist Richard Davis, a Chicago native who had been based in Madison since 1977, where he taught at the University of Wisconsin. The second set included Henry Grimes with AACM reedists Ari Brown and Edwin Daugherty, bassist David “Dawi” Williams, drummer Dushun Mosley, and multi-instrumentalist Douglas Ewart.

A little over a year later, Fred Anderson died on June 24, 2010, at the age of 81. He had been scheduled to perform the day he died. He was playing right to the end - a true jazz warrior.

Fred Anderson’s Velvet Lounge was at the center of Chicago’s creative music boom of the 1990s. It was a beacon of hope out in the Neon Wilderness of the city on the make:

He played an important role in the development of a culture of improvisation in the Chicago area in the 1990s. His commitment and passion towards established and up-and-coming musicians in Chicago were legendary.

Like Fred Anderson, Nelson Algren was also not born in Chicago. Algren moved there from Detroit, the Motor City. But they both loved Chicago, for better and for worse.

Algren wrote in his book, Who Lost an American?

Love is by remebrance, and, unlike the people of Paris or London or New York or San Francisco, who prove their love by recording their times in painting and plays and books and films and poetry, the lack of love of Chicagoans for Chicago stands self-evident by the fact that we make no living record of it here, and are, in fact, opposed to first-hand creativity. All we have of today of the past is the poetry of Sandburg, now as remote from the Chicago of today as Wordsworth’s.

Love is by remembrance, so we must stop for a moment to remember and pay our respects to Fred Anderson. Although he was not from Chicago, his legacy stands to prove Algren wrong - he loved Chicago and its people.

Somewhere between the curved steel of the El and the hockshops on Clark Street, between the Chicago River and the Five & Dime in Evanston, Fred Anderson is caught for keeps at last. If you listen closely, you can hear him…

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of the 1971 film, McCabe & Mrs. Miller.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. I thank you in advance for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel so inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Thank you for this.

This post made me wish I had been living in Chicago in the 80s/90s. I have a lot of the music referenced, but to have heard it live, WOW. I have added quite a few albums to my Bandcamp wishlist. When my wife sees the next cc bill there will be a loud noise emanating from central OK. Music is the Best.

🤘😎🤘