I feel more like a jazz musician when I write my pieces. Like when I write a concerto, I provide two chords or whatever and try to build melodies with certain movements. I feel it’s very important to improvise.

-François Rabbath

When I got out of the service in the late 1980s, I was working at an antique store in Carmel, California. Sometimes after work, I’d drive over the hill to a used record store in Pacific Grove and hunt for West Coast Jazz.

One day, the record store owner told me that he just got in some old Jazz albums - by this time, he knew I was a jazz guy. He told me, “You should take a look at these.” Then he placed six records on the counter:

I realize now that I had stumbled onto a little gold mine. Of particular note is that Oscar Pettiford plays on four of the six albums. It was through Pettiford’s bass and cello playing on these albums that I first developed an appreciation for the sound of a bass.

Not long after this, a friend of mine told me about Paul Chambers’ 1957 Blue Note release, Bass On Top. From that album, Yesterdays made me hear the bass as more than just a rhythm instrument:

It was these two musicians and later others like Ronnie Boykins, Malachi Favors, Abdul Wadud, and Charlie Haden, to name just a few, who helped me continue to nurture my love for the bass and cello. Earlier this year, I learned about another bass pioneer, the Syrian François Rabbath.

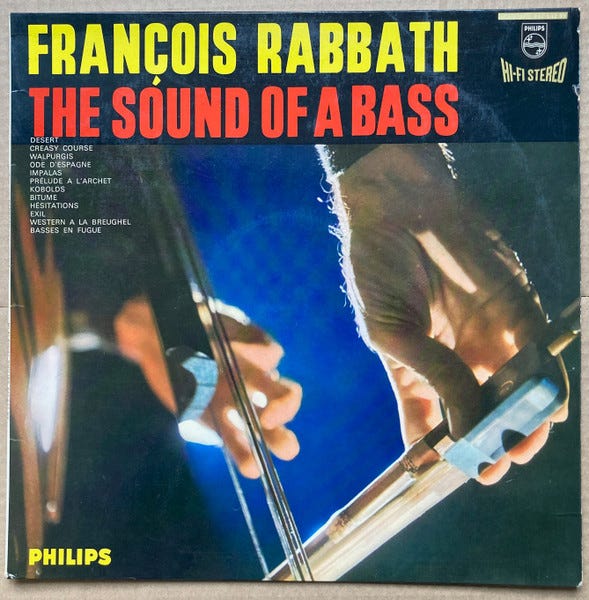

Northwoods Improvisers’ bassist Mike Johnston sent me a link to a Substack piece he guest-wrote recently for Pierre Crépon’s Acoustical Swing. In the article, Johnston highlighted Rabbath’s first album, The Sound of a Bass. When I listened to that album, I was blown away. There it was again - that sound of a bass I had fallen in love with so many years ago.

As it turns out, in June 1989, for Coda Magazine, Johnston interviewed Rabbath, which I have used as a reference for much of this week’s journey.

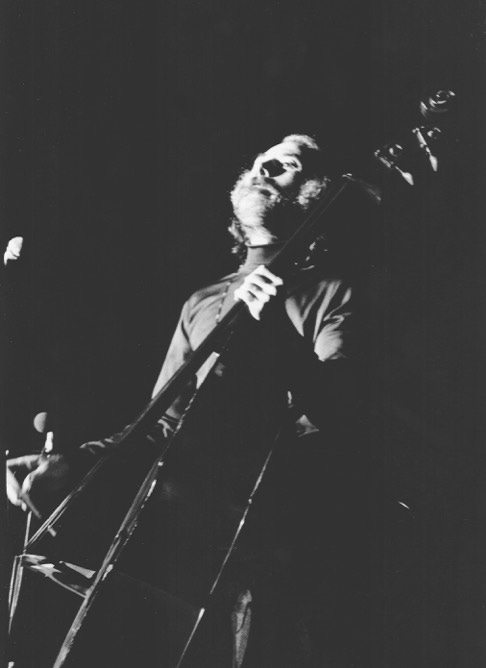

This week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig in our paddles and explore the world of perhaps the most significant double bassist of the 20th century, François Rabbath.

François Rabbath was born in 1931 in Aleppo, Syria, to a family of musicians. He started playing bass when he was 13 years old. His only instruction came from a book written by the Parisian bassist Edouard Nanny, a longtime professor of double bass at the Paris Conservatory. Here’s Rabbath explaining how he discovered Nanny’s book:

One day my mother sent me to the tailor shop to get measured for new clothes. The tailor had a music stand in his shop with a music book on it which was like a display or an antique to him. So when I looked at the music I saw it was ‘Methods of Double Bass” by Edouard Nanny. I was so happy and surprised to see a book like this in Syria. I was afraid to ask him if he could give me this methods book because I thought that it was probably the only book like this in Syria. I could also tell that he saw it as an antique so when he finished measuring me for my pants size and went away to another room I put the methods book under my shirt, or in one word, I stole it. So I learned a lot from this methods book of Monsieur Nanny.

Since he read neither music nor French, it was with much difficulty that he taught himself how to play Nanny’s methods.

Eventually, the family moved to Beirut, Lebanon, where he joined his brother’s band. They played at the Hotel Normandy during dinner hours and then at the nearby Kit Kat nightclub at night. After saving money for nine years, he finally had enough for a year in Paris. So in 1955, eager to go to the Paris Conservatory and show Nanny what he was able to do with the bass, he journeyed to Paris. However, when he applied to the Conservatory, he was disappointed to learn that Nanny had died in 1947.

Sad but undeterred, he continued to study at the Conservatory and soon was playing behind Édith Piaf and Charles Aznavour, sometimes described as "France's Frank Sinatra."

In 1960, Aznavour appeared in François Truffaut's 1960 film Tirez sur le pianiste:

Here’s a trailer for the film:

After an Aznavour performance in Monte Carlo, European big band leader and vice president of Mercury Records, Quincy Jones, heard Rabbath and asked if he had a demo tape. Rabbath told him he did not, and Jones told him to make one and send it to him. Rabbath booked time at Philips Recording Studio, but based on Jones’ interest in Rabbath, the studio manager offered him a contract for two albums.

Rabbath’s first album for Philips was The Sound of a Bass, recorded in 1963:

From this album, here is Rabbath’s composition Désert:

Rabbath’s second album, called simply N°2, was recorded for Philips in 1965:

I could find no record of this album to share on YouTube; hopefully, someone someday will post some tracks.

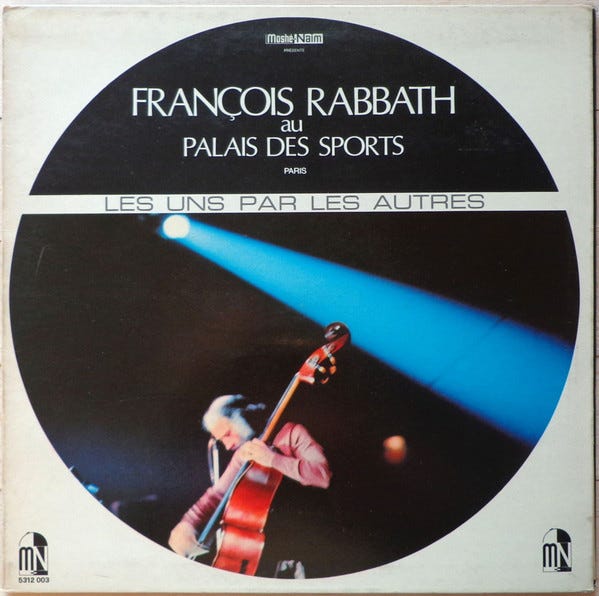

Following these two recordings with Philips, Rabbath recorded three albums from 1971 to 1977 with the French Moshé-Naïm label. The first was his legendary live recording from June 3, 1971, at the Palais des Sports in Paris:

From that concert, here is Creasy Course:

Another classic from the Moshé-Naïm label is his 1977 Sazmorphosis, which features the Saz, a Turkish string instrument. Here is that wonderful album:

All his life, Rabbath has been drawn to painting, sculpture, and poetry. In the Johnstone interview, he shared:

I feel that all art is one and when I compose something I never think of the composition as isolated from other things. I always have been inspired by an image from an oil painting, nature or some idea from a writer. But I think somehow I’m drawn strongest by paintings because the image gives me more ideas than words.

Rabbath felt closest to his painter friends like Dali and Picasso. For example, Picasso asked Rabbath to write music for his painting La Guerre et la Paix (War and Peace), created in 1952, on two large panels in his studio at Fournas in Vallauris.

Here is the War panel:

And here is the Peace panel:

Here is Paix, the fourth movement in Rabbath’s composition La Guerre et la Paix:

Unlike Picasso and Dali, Rabbath never met Chagall. However, he was very fond of his work and composed Chagall De Basse for him:

Rabbath had this to say about Chagall De Basse:

In the Chagall piece, there are three bars and then yes, it’s all left to imagination. We do it one time and that’s all. There are many great improvisers. It’s creation in the moment and it must be kept like that for it to be strong.

Here’s one more for the road. Rabbath’s music legacy is extensive and impossible to cover in this journey. Incredibly, at over 90 years old, he is still recording today. Last year for Museum Records, Rabbath made a recording with HabibiSly called Rabbath Electric Orchesta. It contains a wonderful interpretation of Irving Berlin’s Night and Day. I encourage you to search for it on Spotify or Apple Music.

In 2022, Hans Sturm published an authorized biography called 75 Years on 4 Strings: The Life and Music of François Rabbath. It was written over five years from extensive interviews with François and many others.

Although he faced many challenges as a Middle Eastern immigrant in France, François Rabbath overcame diversity and, with his innovative left-hand technique and pedagogy, revolutionized the way the bass is played and taught. For example, performing Bach’s Cello Suites on the double bass was unheard of when Rabbath started playing them, but now they’re almost considered standard repertoire. Here, Rabbath describes how this came about:

When I started playing the double bass, I was always frustrated that there was so little classical repertoire written for it. I even began to compose some pieces myself, but I knew there must be some other way to find music to play. When I was around 17 I heard Pablo Casals playing the Prelude from Bach’s First Cello Suite on the radio, and I was overcome. It was the first time I’d heard the piece and it immediately gave me goosebumps – it was possibly the most moving performance I’d heard up until then. My first question was: why can’t we play this on the bass? A cellist friend of mine pointed out that Édouard Nanny had written some transcriptions for the bass in the 1920s, but I said I wanted to play them the way I’d heard Casals – in the same octave. ‘That’s crazy,’ he laughed. ‘It’s like jumping off the building and hoping you’ll land safely!’ He even bet his cello that I could never play the First Suite in its entirety. Well, to me that meant it would take time, so I started with the Prelude… It took a long time before I had all 36 movements ready for performance. The first time I performed them all together was in 1973, when I was 42 years old. I played the first three Suites at 6pm, and the last three at 8pm – a huge marathon that I’ve never attempted again! It was in the glorious space of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, and sadly it was never captured on tape.

Incredible. Just like all great journeys, they start with the first step…

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of another bassist, Barre Phillips.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

I thoroughly enjoy your trip down the river jazz. It makes me want to get into listening to jazz though I haven’t yet. As a former writing coach, I find your writing easy to read and quite enjoyable for a know-nothing. Keep up the good work, you’re leading me into jazz. I’m just slow.

Thanks for your article. Just on March 20th I had an opportunity to listen/see bassist Michael Schneider solo in Heidelberg. He learned the technique from Rabbath. Stunning.