I remember when we played in Donaueschinger in '66 or '67 with Globe Unity: Shepp was there, with Beaver Harris, a very good band, two trombones, Roswell Rudd and Grachan Monchur, Jimmy Garrison; they played after us. I think everybody admired Shepp in a way we wouldn't do now. I mean, we were still the young Europeans looking up to them, even if we didn't admit it, we did… I guess it's really normalized now. But those were phases of emancipation; you have to kill your father for a while, or tell him to leave you alone. In the late '60s, early '70s, step by step we did that.

- Peter Brötzmann

My mother was born in 1932 in Sunbury-on-Thames near Twickenham, a small suburb of London.

When she was eight years old, Twickenham was bombed during German air raids, which had started in the UK on October 16, 1939.

The first bomb to strike the area around her house was dropped by the Luftwaffe on the night of August 24, 1940, during a raid on the oil refineries at Thames Haven.

1940 was a tough year. 74 people were killed in the Twickenham area, the highest number of casualties in the war.

My mom told me a funny story about those days during the Blitz. When the sirens went off, as the family hurried to the shelters, her mom would yell, “Where’s Elsie? Find Elsie!” Elsie was not the youngest of her six children, it was the family chicken. Indeed, a valuable family “member” during those lean war-rationed years.

In the summer of 1944, V1 and V2 rockets, unmanned weapons with high explosive warheads, were launched across the channel from sites in the Netherlands and France. These were the “buzz bombs”, and I remember my mom telling me about them. She’d say, “As long as you heard them you were fine, but if the sound stopped, you knew you were in trouble. That meant they were heading down.”

When Twickenham celebrated VE Day and hostilities ended in August 1945, residents could sit back for the first time in five years and take stock of the damage. 143 civilians had been killed in air raids. 500 houses had been destroyed, and another 32,000 residences had sustained damage.

My mom was 13 years old when the Blitz ended.

In March 1940 the Royal Air Force (RAF), in retaliation for Luftwaffe attacks, began bombing military targets in Germany, commencing with the Luftwaffe seaplane air base at Hörnum.

By 1945, allied forces turned their bombing campaign on civilian targets, and in February 1945 the RAF and the U.S. 8th Air Force conducted a series of raids, like the one on Dresden that destroyed much of the city center, resulting in a firestorm.

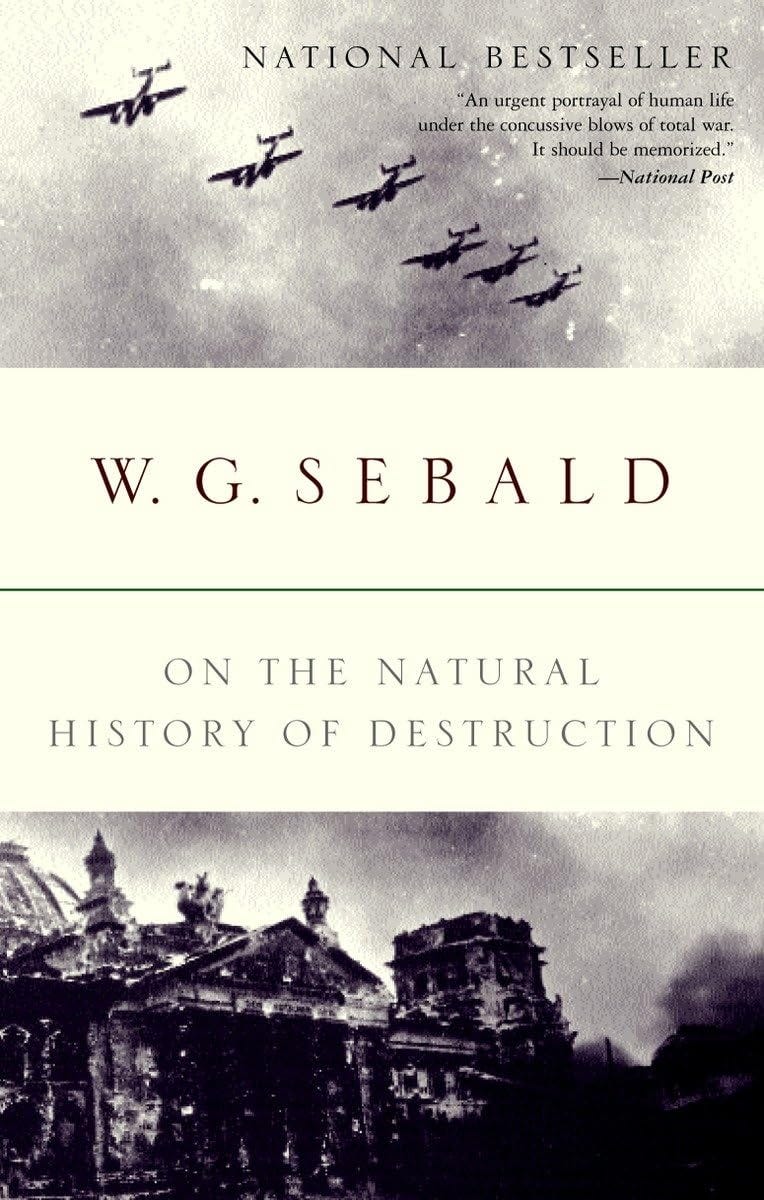

In 1999, W. G. Sebald wrote On The Natural History of Destruction, a fascinating meditation on national guilt, national victimhood, and the universal consequences of denying the past:

The devastation in Germany after WWII was astonishing. During the war, 131 German cities and towns were targeted by Allied bombs, a good number almost entirely flattened. Six hundred thousand German civilians died, a figure twice as large as all American war casualties combined. Seven and a half million Germans were left homeless.

In the book, Sebald wrote:

Today it is hard to form an even partly adequate idea of the extent of the destruction suffered by the cities of Germany in the last years of the Second World War, still harder to think about the horrors involved in that devastation.

Later he adds:

There was a tacit agreement, equally binding on everyone, that the true state of material and moral ruin in which the country found itself was not to be described. The darkest aspects of the final act of destruction, as experienced by the great majority of the German population, remained under a kind of taboo like a shameful family secret, a secret that perhaps could not even be privately acknowledged.

Perhaps most poignant of all, he wrote:

I spent my childhood and youth on the northern outskirts of the Alps, in a region that was largely spared the immediate effects of the so-called hostilities. At the end of the war, I was just one year old, so I can hardly have any impressions of that period of destruction based on personal experience. Yet to this day, when I see photographs or documentary films from the war I feel as if I were its child, so to speak, as if those horrors I did not experience cast a shadow over me, and one from which I shall never entirely emerge.

I share these two war stories because in any discussion about the music coming from post-war England, the Netherlands, and Germany, we must consider it in the context of the war. That was the environment in which the musicians came of age.

As much as Americans like to think that European free “Jazz” was just an extension or copy of the American model, I’m not so sure it was - they had a very different approach to the music.

The “jazz” music from Western Europe in the late 1960s and early 1970s was about emancipation - a call to freedom: in England from austere state control and rationing; in the Netherlands from oppression and occupation; and in Germany from national guilt and victimhood. In the 1960s, European jazz musicians were starting a journey. With the weight of the war on their shoulders and the winds of the past blowing in their faces, they were searching for a way out, a way through the wall.

Whether seeking to extend the boundaries of the known or to escape those boundaries altogether, it doesn’t matter. What matters is they were on a voyage of discovery.

They stood at a place, contemplating time backward and time forward…

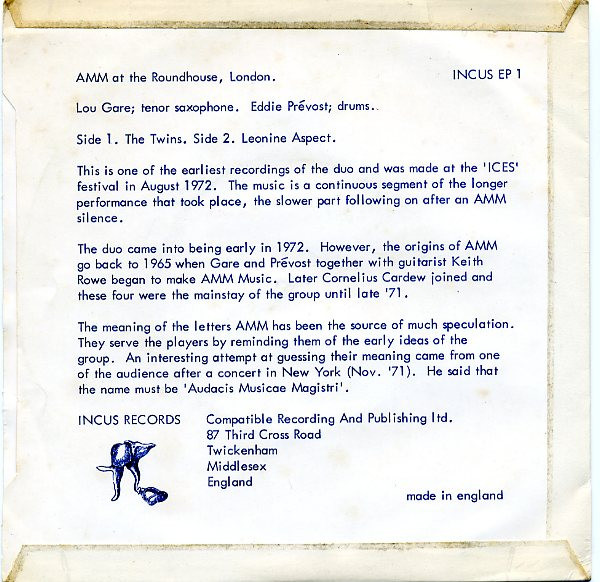

It’s important to note that Derek Bailey was born in 1930, two years before my mother. He grew up in an England racked by austere state control and rationing. In fact, rationing did not end completely until 1954, nine years after the war ended. The UK was the last country involved in the war to stop rationing food. It was out from under this weight that the idea for Incus Records was created, the first British musician-run independent jazz record company.

It was the first British musician-owned music label, founded in 1970 by Bailey, Evan Parker, Tony Oxley, and Michael Walters. Interestingly, it was located then at 87 Third Cross Road in Twickenham in Middlesex, England, only 10 minutes by car from where my mom grew up. You can find the address on Incus EP 1 AMM live at the Roadhouse, London:

Incus’ first release was The Topography of the Lungs, recorded and released in 1970 by Bailey, Parker, and Dutch percussionist Han Bennink. It is considered a milestone in European free improvisation.

In a September 2004 interview with David Keenan from The Wire magazine, British guitarist Bailey points out:

Now I think the whole European thing, that’s no jazz. That’s something else altogether… For me the real interest is starting from nothing. You have no guide, you don’t start from an idiom, like jazz or rock, you start from nothing and see what happens.

Keenan then adds, “Bailey’s playing an exploratory process, one movement of the hands and then the next, every movement a separate sound event, an isolated real-time response, and an indivisible part of a conceptual whole.”

The post-war environment in the Netherlands was entirely different from England and the resulting music was unique to the Dutch experience.

Several prominent Dutch jazz artists grew up in cities under German occupation during World War II, with their lives and careers significantly impacted by the period. For example, Johnny & Jones, an early popular Dutch jazz duo, faced persecution and deportation to concentration camps under the Nazi regime, and musicians like Misha Mengleberg and Willem Breuker were born before the Netherlands was liberated in May 1945.

Beginning with the liberation, the Dutch people’s postwar perspective of jazz music changed dramatically from the music of the American liberators to music deliberately separated from the American model. The Dutch baby boomers, born between 1945 and 1955, hit their adolescence in the early 1960s, bringing a different perspective. They felt that American jazz had become stagnant. To mark their independence, younger Dutch musicians dropped the word “jazz” altogether and replaced it with the term improvisatiemuziek (improvisation music).

In the Dutch magazine Jazzwereld, Bennink stated:

(The American-avant-garde) has stopped progressing since 1964. No, even worse: it has gone downhill. You know what is crazy? I’ve read that there are jazz-excursions from the Netherlands to America. There’s no need for that, as far as I’m concerned. Those trips go the wrong way. They should have trips for Americans, to come our way!... There is no American avant-garde. There is no European scene either. Believe me, currently the best music can be heard in the Netherlands.

More importantly, because the Dutch jazz establishment did not take their music seriously and Dutch record companies were not interested in recording this new “improvisation music”, in 1967 saxophonist Breuker, pianist Mengelberg, and drummer Bennink founded the Instant Composer Pool (ICP) cooperative in Amsterdam. They also created ICP, the first Dutch musician-run independent jazz record company. Their first release was New Acoustic Swing Duo recorded and released in 1968.

In the same way that the post-war environment differed between England and the Netherlands, Germany experienced a unique cultural environment.

Like Derek Bailey, Peter Brötzmann was born before the war ended. He came of age during a time when Western Germany suffered from national guilt and victimhood and was still occupied by Allied forces. It was not until May 5, 1955, that the Americans, British, and French ended their nearly 10-year occupation.

Brötzmann once said:

I don't know exactly why that was, I never had it, but I remember in the early years, late '60s and early '70s, there was quite a strongly expressed opinion against including Americans on festival programming… Well, it was two things at once. You still admired the American musicians, but you also were saying you didn't need them. Very normal father relationship.

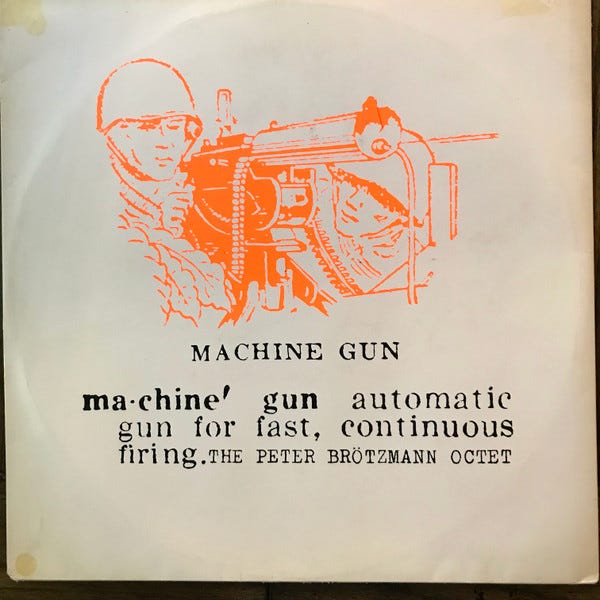

I think European free improvisation started with Brötzmann’s For Adolphe Sax, which was financed, recorded, and released in June 1967 on his BRÖ label, the first German musician-run independent jazz record company. It is a trio album with Brötzmann on sax, German Peter Kowald on bass, and Swede Sven-Åke Johansson on drums. The following year, again on the BRÖ label, Brötzmann with an octet released the seminal Machine Gun:

When he released Machine Gun, Brötzmann felt the time was right. With West Germany’s ongoing recovery from WWII, the free-style music was a critique of what he perceived as a sick and stagnant society. He recalled to Steven Loewy in a 1999 Coda interview:

It was a special time in Europe: the Vietnam War and the campus radical. These were revolutionary times, extremely radical. Our fathers left us with so many unanswered questions after the World War. We wanted to destroy everything our fathers stood for. We wanted to change the world. But, of course, the notion that our music could make that sort of change was an illusion.

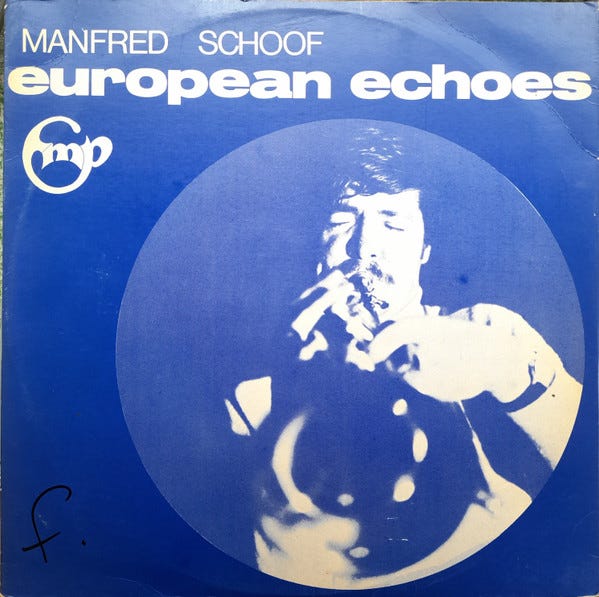

Along with Peter Kowald and Jost Gebers, Brötzmann created Free Music Production (FMP), a cooperative to promote a democratic base to create, record, and distribute the revolutionary free music of primarily German musicians. FMP’s first release in 1969 was Manfred Schoof’s European Echoes:

During the end of the 1960s, Brötzmann believed that the Germans more than the British or Dutch were the most American-oriented. Perhaps this was due to American forces in occupied Germany after the war. Many American jazz musicians stayed or soon returned to Germany and joined bands. Also, America’s Armed Forces Radio and West Germany’s WDR in Köln played a lot of American jazz music.

So while Germany’s free jazz featured a slightly more American touch, the British offered a more intellectual approach. The Dutch were very different, using humor and a more social, theatrical approach. Regardless of their differing influences and cultural sensibilities, they were all on a journey of discovery. These European musicians and their cooperatives no longer wanted to deny the past. They were searching for a way out of the past and it was historic.

Peter Brötzmann tells the story of meeting John Gilmore from the Sun Ra Arkestra. They played together in a large band at a festival. After the concert, Gilmore asked him, “Brötzmann, how do you do it? There are no harmonies, there’s no nothing!” Gilmore was surprised that such a thing was possible. That is a key point. The history of jazz didn’t shackle the Europeans as entertainment or music to dance to. They viewed it as a kind of art process independent from that history, independent of pleasing somebody. Brötzmann states prophetically:

We just used the music to find out what’s going on within ourselves.

Evan Parker once said, “That’s how it is. Music, freely improvised group music especially, is a way of stepping through the wall to another place where things are, in some ways, more straightforward.”

In many ways, the 1991 North Sea Jazz Festival is when I stepped through the wall. It was like traveling a river and turning the bend to discover a large, beautiful body of water you did not know existed. I was aware of the Kollektief and to a small degree the ICP, but unaware of the greater transnational improvisational movement in Europe in the late 1960s. However, on the other side of the wall was the color and flare of other European musicians like Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Han Bennink, Misha Mengelberg, and Peter Brötzmann. This movement existed outside of the Free Jazz movement in America. From then on my perspective of jazz widened - no longer American Jazz dominated.

In his novel Invisible Man Ralph Ellison wrote, “If you want to know who I am, you must know where I came from.” As I think about the European free jazz musicians in the late 1960s, they were trying to understand their backgrounds and identities to fully grasp who they were. They were looking for passes through the mountains and deserts they were about to face - needed to face. It’s the same way through the mountain passes and across the desert for all of us - time backward and time forward.

Next week will be the 109th running of the Indy 500, which started in 1911. The race is always run on Memorial Day weekend. To celebrate the race, on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of Dave MacDonald’s 00 Corvette Special.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Thank you for this excellent article. With the benefit of hindsight it is possible to see the European Free Improvisation scene as the first truly European jazz style. I can see why some people would argue it isn’t jazz, or that maybe Django and his followers deserve that distinction. Does it matter though? The music is certainly influenced by jazz, and is highly compatible with free jazz. It is also amazingly good. I had the good fortune to hear Brötzmann live a few times and they are among the best concert experiences of my life.

I do not blame you for the Pretensions of European Imposters.

I am just fighting a „European Jazz Musicians Disease“ that still lingers on here in Europe.

The whole Thing has to do with Public Founding of Jazz in many European Countries and with getting recognized by European Promoters.

Mixing Jazz with Local Music of its own Country can give you Money if the Music still falls under the Rubric Jazz.

Money it wouldn’t get if it was considered „Classical“ coz the Classical Founders surely look extremely for what they accept.

Many think that their Music becomes more significant if they Mix Jazz with „Their Traditions“.

But what are their Traditions?

Even though the Habsburgians came from what is Switzerland today, the Music they fostered so effectively began long time after the Habsburgians were driven out of Switzerland by armed Force.

Switzerland has no own „Classic Music“ Tradition, so Music from a Country like the USA is actually not any stranger to Switzerland then European Court Music.

But if you fuse European Court Music with Jazz your Chances are much bigger to get grants as if you fuse Jazz with Tex Mex or the Country Music by the Glaser Brothers even though these Traditions have closer Links to Swiss Ländlers, than the Habsburgian Court Music has.

Many Europeans claimed in the 70ties that they want to get rid of the American Swing Dictatorship.

I say if you don’t want to swing, don’t call your Stuff Jazz, call it something else.

If you do not know the Difference between a Blue Note and a Minor Third, you might play European Impressionistic Bar Music with a Swing Feel but not Jazz.

I love Non-Idiomatic Free Music and I know that this Music has to be played in Jazz Clubs otherwise it wouldn’t be played at all, but it should not be smuggled in under the Umbrella „Emancipated European Jazz”.

I allow myself to call every European who wants „Emancipated European Jazz“ a „Latent Racist“.

They shall play their Music but they shall not call it Jazz.

I might listen to their „Jazz-Influenced Explorations“ with much more respect.