I could compare my music to white light which contains all colours. Only a prism can divide the colours and make them appear; this prism could be the spirit of the listener.

- Arvo Pärt

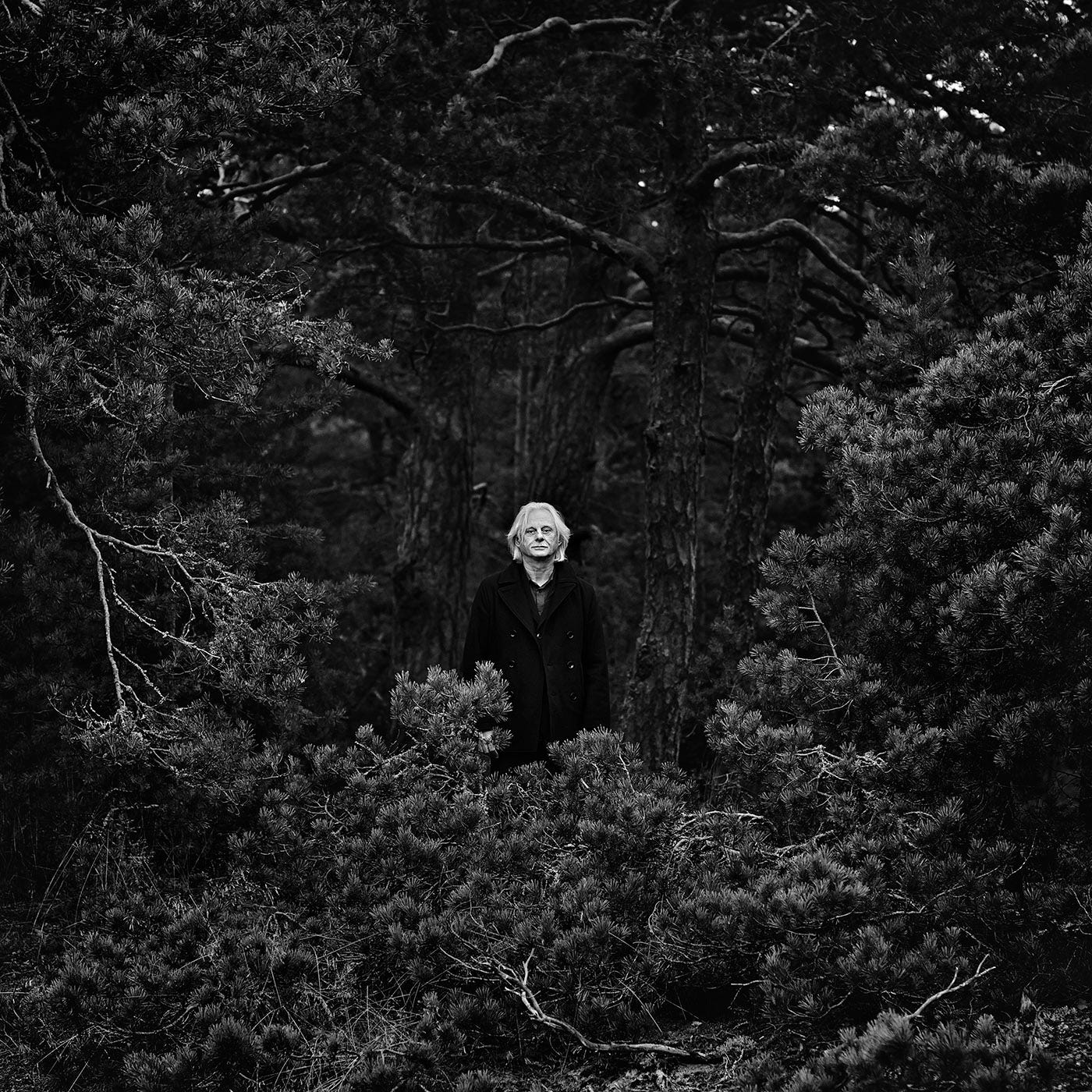

For over 50 years, Manfred Eicher has been alone in the forest. But is he really alone….

The rigorous principles he has held over his recordings created a unique body of music that transformed contemporary jazz. Many critics have been skeptical of his musical philosophy, claiming he suffocates musicians and stifles creativity, and that ECM is cold, soulless, and dull. Eicher responded by withdrawing advertising and refusing interviews. Through it all, he quietly built perhaps the greatest independent record labels, allowing him to focus just on the music. “I’ve had great luck in being able to do what I want, without answering to anybody, with no corporate boss in the back,” he told DownBeat magazine in a 2019 interview. “We’ve been able to keep it going all this time.”

The conventional wisdom is that ECM was hostile to atonal or avant-garde music, but I don’t believe that is true. From the start, Eicher backed eclectic and unforgiving experimental albums such as Peter Brötzmann’s Nipples (1969), which he produced for the Calig record label before he even started his ECM label; and Marion Brown’s Afternoon of a Georgia Faun (1970), which I featured above - when you have 20 minutes or so, I encourage you listen to the entire title track.

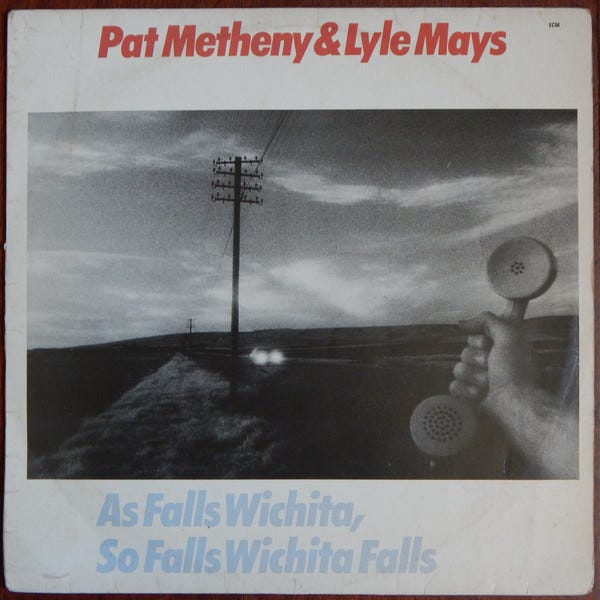

The ECM catalog is vast and defies easy description; however, one recurring thread has been an inward, meditative, and even spiritual quality. That is exactly the way I felt about my first ECM record: Pat Metheny & Lyle Mays 1981 As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls.

It was actually not an album, it was a cassette. I bought it in NYC at Tower Records, and I played it over and over as I drove down to Fort Benning, Georgia. Then, after Airborne School, I played it again from Georgia all the way to Fort Lawton, Oklahoma. I played mostly that one, but also Pat Metheny’s 1979 New Chautauqua. These were the perfect road records - peacefully hypnotic. For example, here’s Country Poem from New Chautauqua:

The Beginnings

Manfred Eicher was born in 1943 in Lindau, an island on Lake Constance in Bavaria. Growing up near Lake Constance in the south of Germany with four older sisters, at age six he was encouraged to learn the violin by his mother, who was a singer. Within a few years, he could play the Bach partitas. He inherited his mother’s love of the Schubert Lieder and got into the late Beethoven quartets. As a youngster, he lived on yogurt and coffee so he could buy records, won a scholarship to the prestigious Berlin Academy of Music, was a production assistant on recordings by Herbert von Karajan, principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic for 34 years, and indulged his abiding passion for jazz by attending concerts and clubs. Classically trained, the first record he bought was “at the end of the Fifties, Klemperer recordings of Mahler.” Pop music of the Beatles kind went right past him, saying, “I noticed it but it never had an impact like chamber music and Miles Davis.”

His experience working as a professional musician shaped his future approach to working “on the other side of the microphone” as a producer. He was inspired by the Bill Evans trio with Scott LaFaro, Paul Bley, and Jimmy Giuffre, but, he said, “I wasn’t sure I could ever be close to these wonderful music players—but as a good listener and as someone who dedicates his hearing towards this music I thought maybe I could contribute more to the music some way other than as a player. I felt I enjoyed listening. I was from the beginning very interested in how things are transferred to sound or tapes and this was something I really enjoyed—maybe that could be something one day for me to do would be to be an engineer or produce, to be someone who is taking care of making the musicians sound better…”

In the late Sixties, “I was listening to people like Ornette Coleman, Paul Bley, Cecil Taylor, and Bill Evans, but as far as recording was concerned, nothing interested me. ESP Disk was interesting. But they had a strange production quality because they were mostly recorded in living rooms and didn't have the precise shape and sound this music deserved.” He goes on to say:

“I wanted to do something from my cultural background as a European with my awareness of what classical engineers would do. I wanted to explore a different sound picture than we had at the time. I wanted to record things with the utmost detail possible, to get a sense of transparency, to get close to the musical structures. At the beginning, we didn’t have a fixed concept, but there were musicians that I really liked. The idea was to approach improvised music with more of a chamber-music sensibility.”

With that goal in mind and money borrowed from the owner of a local discount records shop, Karl Egger, who ran the Elektro-Egger record store, he started his own independent record company in Munich: Edition of Contemporary Music - ECM. The store played a key role in the label’s origin, offering Eicher those first, important record-making opportunities.

ECM’s first album was prophetically titled Free at Last, recorded by expatriate American pianist Mal Waldron. It was recorded on November 24, 1969, at the Tonstudio Bauer, in Ludwigsburg near Stuttgart, Germany, and released in 1970. The company pressed 500 copies and eventually sold more than 14,000. That would be the first of many more to come….

But to go deeper into the forest, where did that ECM sound come from?

I think some of that answer comes from two important re-releases in the ECM catalog. In all the thousands of releases on the ECM label, I can find only two records, besides Marion Brown’s Afternoon of a Georgia Faun and Paul Bley With Gary Peacock from the very beginning, that were recorded by someone else and released by Eicher on his ECM label.

The first is the Jimmy Giuffre 3, recorded by the Verve label in NYC at Olmsted Sound Studios on March 3, 1961. Eicher remastered this record and released it on ECM in 1993. The other was Arvo Pärt’s Tabula Rasa recorded in Bönn in November 1977. Eicher remastered this recording and released it in 1984.

This is purely speculation on my part, but if I had to guess, I think these rather obscure musicians had a big impact on the ECM sound. First, we’ll look at the Jimmy Giuffre influence.

Jimmy Giuffre 3

Jimmy Giuffre wrote Four Brothers for the Woody Herman big band and then went on to fame during the 1950s with the Lighthouse All Stars and Shorty Roger’s Giants - names you’ll remember from past journeys if you’ve stayed with me this long.

In 1961, the Jimmy Giuffre 3 recorded two important albums in New York City: Fusion recorded on March 3, 1961, in New York, and Thesis recorded on April 8, 1961, in New York. His trio consisted of Jimmy Giuffre clarinet, Paul Bley piano, and Steve Swallow double-bass. These albums were produced by Creed Taylor for the Verve record label.

Also in 1961, the trio toured Europe. German jazz critic Joachim E. Berendt said it best by describing how the trio explored free jazz not in the aggressive mode of Albert Ayler or Archie Shepp, but with a hushed, quiet focus closer to chamber music. The Jimmy Giuffre 3 was an early spark that fueled the later free improvisation boom in Europe.

Here is a live recording of the Jimmy Giuffre 3 on that 1961 European tour playing in Stuttgart. I’ll bet Eicher was at this concert.

I think this trio had an immediate and significant impact on Eicher and helped him develop the chamber jazz sound that would become the hallmark of the early ECM sound. The second major influence was the Estonian composer of classical and religious music: Avro Pärt.

Arvo Pärt

Arvo Pärt graduated from the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre in 1963. During this time, he was only able to encounter musical influences outside the Soviet Union from illegal tapes and scores. When he began to compose using Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique and serialism, the Soviet Union banned his work and he entered a period of “artistic reorientation”. However, in 1976, he emerged from this period and composed Tabula Rasa, one of his earliest compositions to reach Western listeners outside of the Soviet Union.

Tabula Rasa was composed at the request of Eri Klas, a friend and conductor, who asked Pärt to write a piece for an upcoming concert to accompany Alfred Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso, which was scored for two violins, prepared piano, harpsichord, and string chamber ensemble. The piece was dedicated to Latvian violinist Gidon Kremer. Kremer premièred the piece in Tallinn, Estonia, on 30 September 1977, along with Russian Tatjana Grindenko, on solo second violin, Russian Alfred Schnittke on the prepared piano, and the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Eri Klas. However, it was a November 1977 performance in Bönn that was the most important because it would result in Eicher creating the ECM New Series label. Eicher first encounter with the music of Pärt was almost by chance. Eicher remembers:

“It was in the beginning of the 80s on a moonless night. I drove by car from Stuttgart to Zürich on the Autobahn near Lake Constance, very slow because my car was not driving the best possible way on a flat tire. There was some music, it was so beautiful, like angel music, and I stopped the car. I drove out to a hill for better reception and listened to the whole piece. It took me one year after this point to find out what the music was. It was one of the first recordings of Tabula Rasa.”

Here is a short video of Eicher talking about this chance encounter:

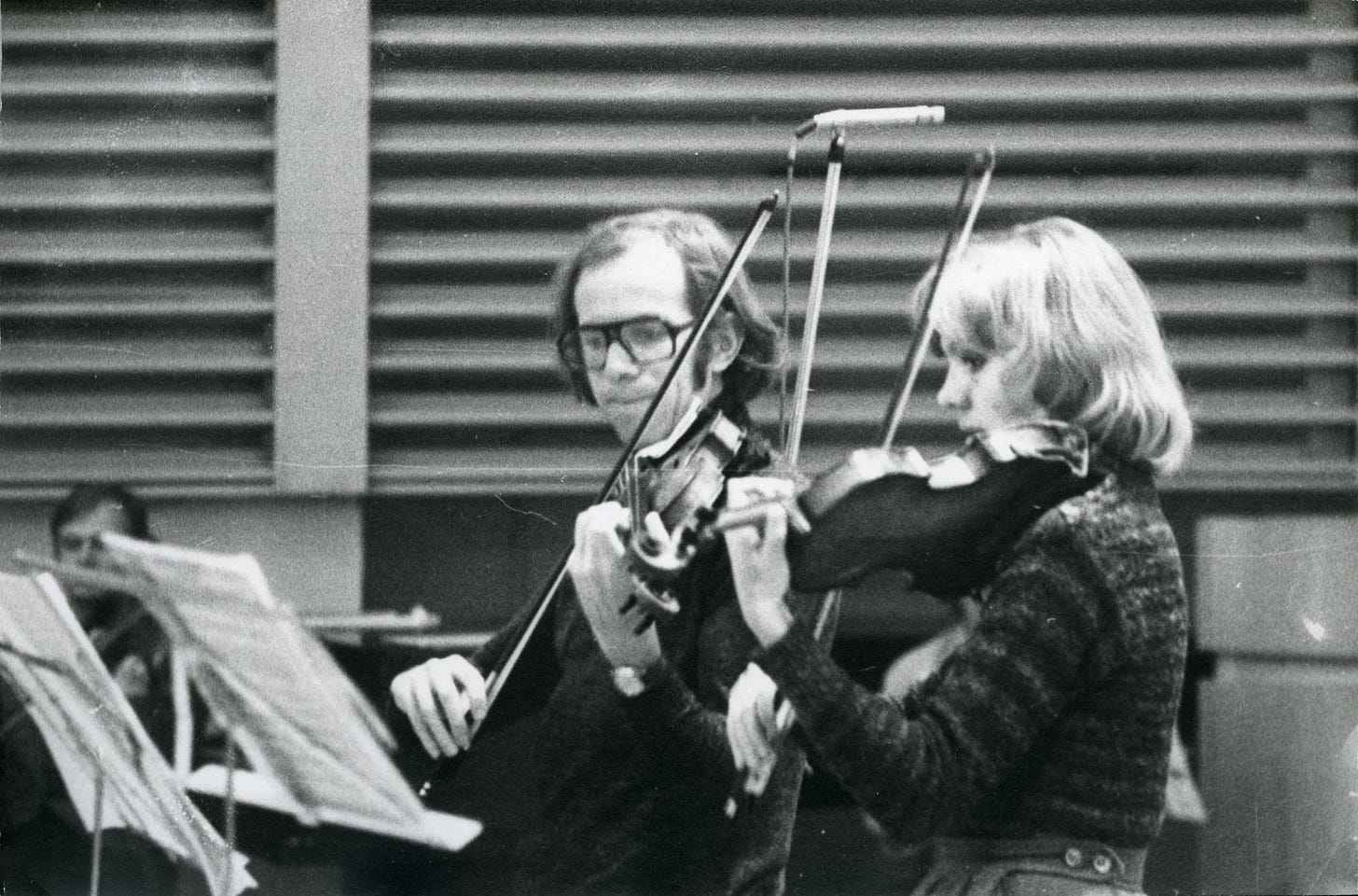

Eicher initiated the ECM New Series label in 1984 with an album dedicated to the music of Arvo Pärt, which included the 1977 Bönn recording of Tabula Rasa. Here are Kremer and Grindenko practicing Tabula Rasa before the September 1977 premiere.

The ECM New Series label focuses specifically on classical music. Eicher saw these two idioms, jazz and classical, as symbolic representatives of the creative tension between form and content. “One line deals with music created primarily through improvisation,” Eicher explained to interviewer Josef Woodward. “The other line starts from the carefully realized score. Both approaches are important to me—form and freedom. I benefitted from one and the other.”

As I have tried to explain, I think it was jazz music like the Jimmy Giuffre 3 and classical music like Tabula Rasa that had a huge impact on Manfred Eicher in those early days and would continue to guide him, as he defined and broadened the sound for his ECM label.

If there is a flagship ECM artist, it is Keith Jarrett, whose first ECM title was the 1972 studio solo album Facing You. A few years later, Jarrett recorded his most popular album—also ECM’s most celebrated title: The Köln Concert. The landmark solo piano improvisation opus was recorded in January 1975, at the Opera House in Köln, Germany. Today, it has sold millions of copies and appeared on many “Best Jazz Albums of All Time” lists. However, even though Jarrett’s My Song with his “European Quartet” featuring Jan Garbarek, Palle Danielsson, and Jon Christensen may be my all-time favorite ECM album, his music was never my favorite.

If you ask 10 people what their favorite 10 ECM records are, you probably get 10 different lists. That’s the nature of this dense label. So here are my top 10 songs, and I’ll add them to my Spotify playlist. ECM tracks are nearly impossible to find on YouTube, so I’ll list them here and ask that you tune into my Spotify playlist to hear them:

Lonely Woman, Rejoicing 1984

The Colours of Chloe, The Colours of Chloe, 1974

If I Could, First Circle 1984

The Bat pt.2, Offramp, 1982

Tabula Rasa, Tabula Rasa, 1984

It’s For You, As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls, 1981

Prayer For Jimbo Kwesi, The Third Decade, 1985

The Journey Home, My Song, 1978

Obsecro Te, Secret History, 2017

I Only Have Eye For You, I Only Have Eye For You, Lester Bowie’s Brass Fantasy, 1985

ECM album covers are austere and rarely come with liner notes, in fact, very little information is provided at all. Eicher, for his part, gives few interviews, and he seems to have little interest in discussing his life’s work. However, the ECM sound is rich and ahead of its time. According to Eicher: “Our concept is still more or less the original idea of producing music that I love and that I would like to introduce to people. That's all it is, and it has not changed and will not change because it's the only thing I can do."

So while Manfred Eicher has been alone in the forest for over 50 years, I don’t think he feels alone because the forest is music, and his strength is his faith in the music—and only the music.

Here’s one more for the road. A stunning live version of one of my favorites from the As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls album. The song September Fifteenth is in reference to September 15, 1980, the day jazz pianist Bill Evans died.

Next week, I’ll portage the canoe and take some time off. It’s been almost a year straight of weekly journeys with you all, and I’ve had a great time. I want to thank you all for riding with me on that Big River called Jazz. I’ll put the canoe back in after this short time of reflection or “artistic reorientation”. I encourage you all to re-read some of our past journeys or just get caught up….

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button at the bottom of the page. Also, if you feel so inclined, become a subscriber to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe” button here:

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that….

Until then, keep on walking….