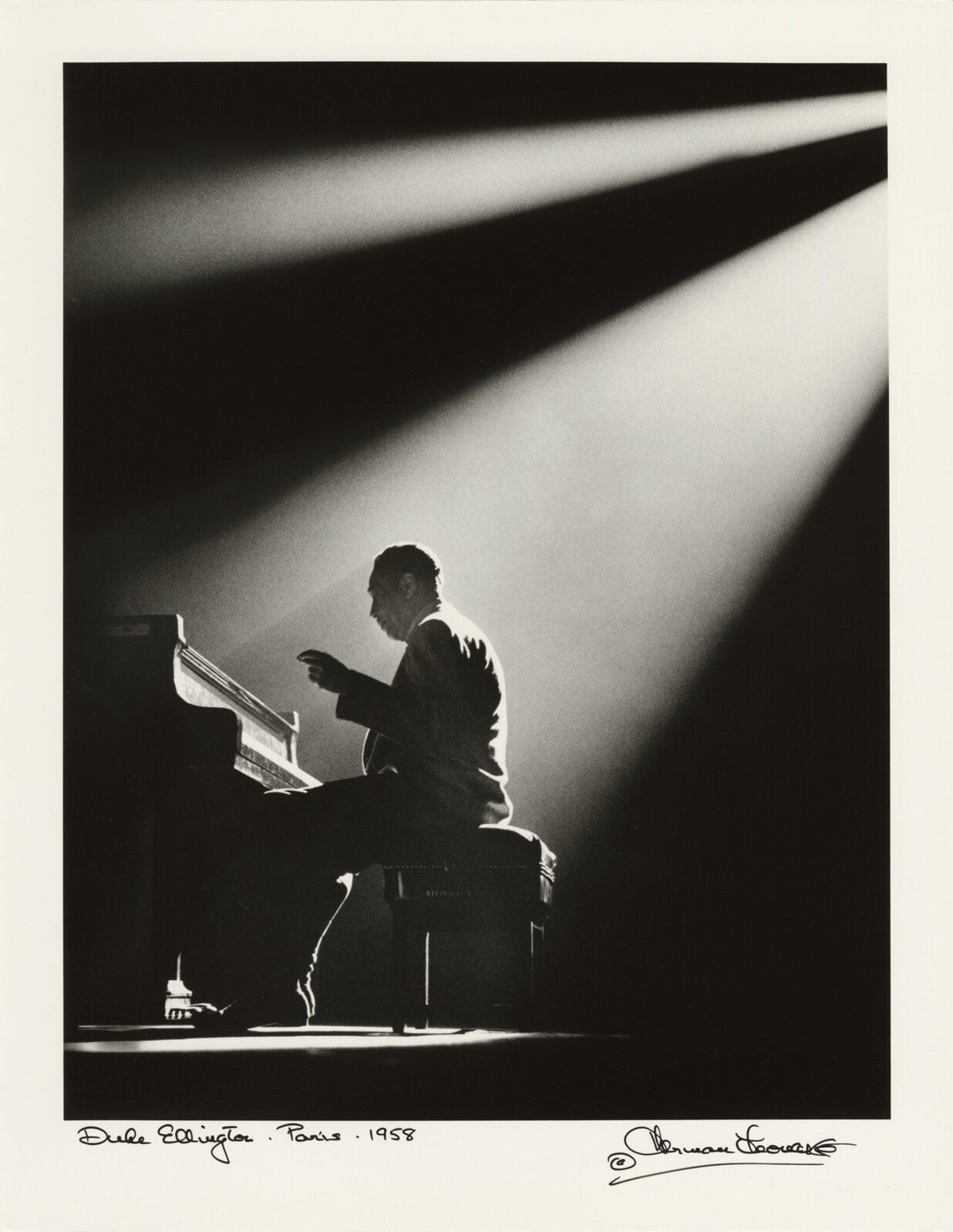

There has never been a serious musician who was as serious about his music as a jazz musician.

-Duke Ellington

I was still in high school in 1977 when Woody Allen’s Annie Hall came out at the movies. I didn’t see it then. I was much more likely to go see a James Bond or Bruce Lee movie. I do recall the movie had an impact on the way some of the girls started to dress in school, which I liked.

Probably a decade after it was released and I was out of college, I finally did see Annie Hall. I must have rented it from a video store in Monterey, back when you did that. I thought one of the funniest scenes was when Woody Allen pulled this old guy out from behind a screen to confront an obnoxious guy standing behind him in line at the movie theater:

I remember thinking, who was that guy? When the credits rolled, I noticed it was Marshall McLuhan. I had never heard of him; however, I would remember his name.

Not too long after seeing Annie Hall, I started to listen to Duke Ellington. There was no connection. I just was digging into jazz in general and wanted to learn more about his music. His albums were pretty common in the used record stores. The first few I remember buying were Soul Call and First Time! The Count Meets The Duke. Then I found this one, Afro-Eurasian Eclipse:

In a strange twist of fate, as Ellington introduces the first track he mentions of all people Marshall McLuhan. I remember thinking, “Hey, that’s the guy from Annie Hall.” But I honestly didn’t give the reference much thought. I just remember liking most of the songs and it remains a classic album in my book. I can’t figure out why it never seems to get much attention.

Over the years, I’ve thought more about Ellington’s McLuhan reference. Here’s what Ellington says McLuhan said:

The whole world is going oriental and that no one will be able to retain his or her identity, not even the Orientals.

I wonder if McLuhan actually said that - was it a direct quote? I’m not sure, but Ellington seems to have agreed with the sentiment. Also, Ellington and McLuhan knew each other, so I suspect they had some dialog about it. My conclusion is that I can’t say if he’s supporting McLuhan’s view or disputing it. My guess is the latter. I think the answer comes from what Ellington said next:

We have adjusted our perspective to that of the kangaroo and the didgeridoo. That automatically throws us either down under and/or outback. And from that point of view, it’s most improbable that anyone will ever know exactly who is enjoying the shadow of whom. Harold Ashby has been inducted into the responsibility and the obligation of possibly scrapping off a tiny bit of the charisma of his chinoiserie.

Clearly, Ellington is calling into question who is being eclipsed by whom. If we look back over the half-century since Ellington said “it’s most improbable that anyone will ever know exactly who is enjoying the shadow of whom,” I think he has been proven correct. I contend that the Western (Afro) influence is every bit as strong as the Eastern (Eurasian) influence.

In a 1967 informal and unpublished interview with McLuhan by Indian-Canadian artist P. Mansaramu, McLuhan addresses the question:

…the whole world is an East/West happening, and while the Western world is going Oriental, the Oriental world is going Western. This has been going on for a century, and so what could be a bigger East/West happening than that? See, all the Western artists have gone Oriental since Baudelaire, and all the painters, all abstract art is Oriental art.

I do think McLuhan sees it as a mutual influence of Western and Eastern cultures in our global village; however, he’s addressing the question in the context of the especially strong Eastern influence on Western culture in the 1960s. In response, Ellington is just saying, “Not so fast, Marshall.” Although Annie Hall came out after Ellington passed away, I wonder if he would have used here that "you know nothing of my work” line on McLuhan.

In 1971, Ellington was well aware of the growing popularity of world music and Eastern sounds in music; however, he also knew American music was not being eclipsed by it, rather it was American music such as jazz and blues that was beginning to influence the rest of the world.

On the heels of the recent solar eclipse and Duke Ellington’s birthday, this week on that Big River called Jazz we explore the world of his late masterpiece Afro-Eurasian Eclipse.

Afro-Eurasian Eclipse was recorded in 1971 but not released by Fantasy Records until 1975, a year after Ellington had passed away. It was one of three suites recorded in the first half of 1971 but unreleased in Ellington’s lifetime (the others are the Goutelas and Togo Brava suites).

When I first listened to Afro-Eurasian Eclipse, I was only listening to music, unaware of any social or philosophical context. I judged music on my merit alone - following Ellington’s adage, "There are two kinds of music: good, and the other kind." Over time, I have become more aware of the nuances of an album’s artwork or title. I can say now that this album’s title confounds me, as I find hardly anything on it sounds “oriental” or Asian.

With Afro-Eurasian Eclipse, Ellington was emphasizing that Eurasia was also enjoying the shadow Afro music. Throughout this album, Ellington was saying you can take the blues, use another language to change the title, and call it world music or rock n’ roll, but it is still the blues, arguably the root of most American popular music. A deep dive into three songs helps me see this more clearly.

The first song on the album is Chinoiserie and although it is a great song I find it has no “oriental” feel or sound:

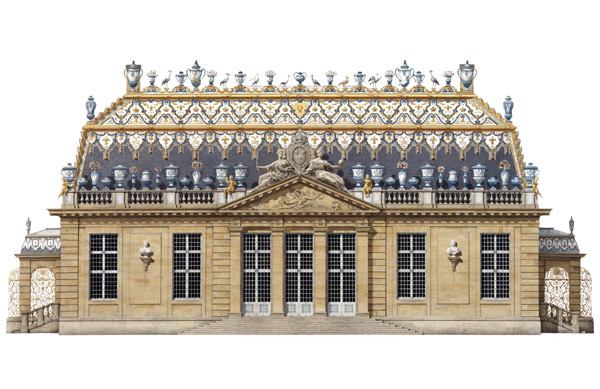

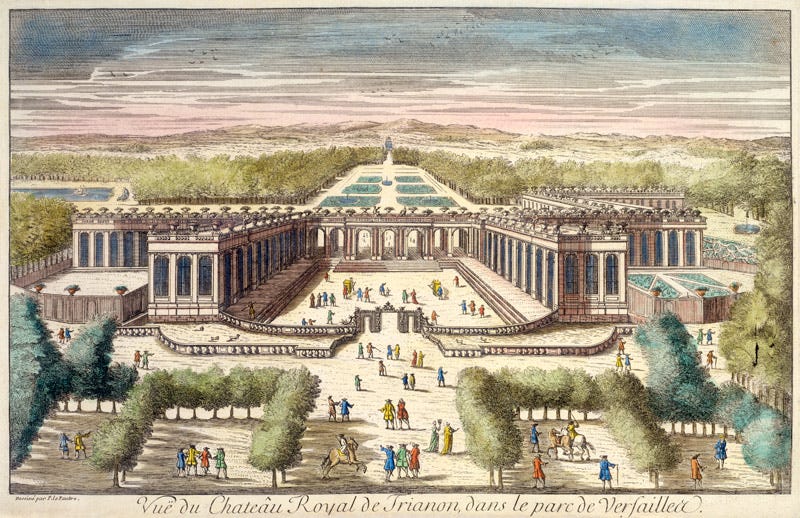

Ellington has also given it an interesting title. Chinoiserie was a European interpretation and imitation of Chinese and other East Asian artistic traditions and became a novelty in European design, which had long followed the rules of classicism and baroque design. The tipping point in chinoiserie’s popularity was in 1671 when King Louis XIV of France built on the grounds of the Palace of Versailles the Trianon de Porcelaine, a five-pavilion structure bedecked with blue-and-white tilework:

Ever the fashion trendsetter, Louis XIV’s fondness for chinoiserie quickly spread throughout European courts and became a popular design style in the 18th century. However, by the 19th century, chinoiserie fell out of vogue mostly due to the rise of other “exotic” aesthetics such as Japonisme, Egyptian Revival, and Moorish Revival.

By 1687, Louis XIV's new mistress, Madame de Maintenon, disliked the building and the exterior’s decorative tiles were cracked and badly weathered. As a result, he had it demolished and replaced by the Grand Trianon, a more permanent French Baroque structure designed by Jules Hardouin-Mansart.

The irony of this title is that it speaks to the fleeting nature of chinoiserie and the Trianon de Porcelaine, which stood for only a short time. However, contrast this with the artistry of Duke Ellington, which has withstood the test of time.

The second track on the album is Didgeridoo. The didgeridoo is a wind instrument played by vibrating your lips and circular breathing to produce a continuous drone. It was developed by the Aboriginal peoples of northern Australia at least 1,000 years ago. It looks like this:

You can hear what the didgeridoo sounds like at the beginning of the opening track from the 1971 movie Walkabout:

Here’s Ellington’s take on the didgeridoo. Listen for the songs last few notes when Harry Carney blows his baritone sax to sound like it could be a didgeridoo. This begs the question: is the baritone sax little more than just a souped-up didgeridoo?

Again, I find hardly anything down under and/or outback in this song. It sounds more like background music from a club in an Austin Powers movie.

Finally, the first song on Side Two of the album is Gong. Now, this is the album’s only song that I can say might sound somewhat “oriental”:

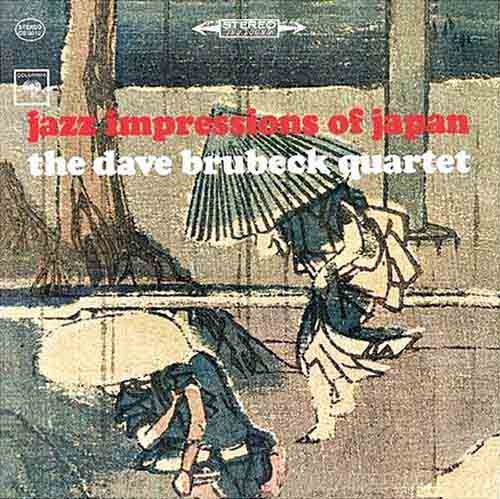

If played by a quartet, it sounds like it could have been squeezed into Dave Brubeck’s 1964 Jazz Impressions of Japan:

Most of the songs on Brubeck’s album sound much more overtly “oriental”. For example, Koto Song has that feel and sound:

Ellington could easily have presented these compositions with a more “oriental” feel. However, his songs have a deliberate “occidental” feel, even the oriental titles seem like a kind of head-fake. I also find it interesting that Ellington included the “Eur” in Eurasian, which brings Europe into play. His song Acht O'Clock Rock hints at an Afro influence in the newer music in Germanic-speaking countries.

Ellington’s introductory rhetoric in Afro-Eurasian Eclipse certainly critiques the world music genre. However, he tries to prove that the world is not going Oriental, but rather that the influence of Western music is growing and moving eastward.

And here is where Woody Allen pulls Duke Ellington out from behind the screen to tell me, “You know nothing of my work… how you got to write about jazz is totally amazing.”

As I write this, it is Duke Ellington's 125th birthday anniversary. No other bandleader created as much and contributed as much to American music as he did. In the end, he proved that even in jazz leadership does matter. What set Ellington apart as a musician, composer, and bandleader was the bon vivant leader of men himself, Duke Ellington.

Vive la Ellington!

Next week, on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig in our paddles to explore the world of the Duality of Birds.

If you like so far what you’ve been reading and hearing on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

Until then, keep on walking….

McLuhan, among his many and complex intellectual skills, was a James Joyce scholar, and this famous quote from “Finnegan’s Wake”appeared in “The Medium is the Massage”:

“The West shall shake the East awake, while ye have the night for morn.”

When I was at UCLA, I took a Duke Ellington class taught by Kenny Burrell. I remember this album!. Vive la Ellington!