Douglas Records

Notes from the underground...

At the end of 1970 it was over in a minute. I woke up and closed everything down. Our audiences we gone… [They] had gotten off the streets and gone back to work. The whole underground symphony was over.

-Alan Douglas

In the early 1980s, I was a freshman in college and living in New York. At that time, I was more of a blues guy and just discovering jazz - my jazz journey was just beginning. I should say it had already started in high school, but I didn’t know I was listening to it.

While walking around Greenwich Village one day, I discovered Bleecker Bob’s record store. I went in and bought Electric Guitarist and My Goal’s Beyond, both by John McLaughlin, who I knew from Flame - Sky on Santana’s album Welcome. In particular, My Goal’s Beyond on the Douglas record label caught my eye because of the song Blue in Green, which I had recently discovered on Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue.

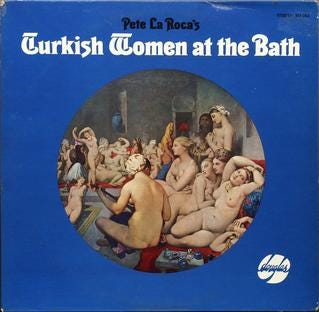

By the end of the 1980s, after seeing the Arkestra a few times in California, I started following Sun Ra and became a huge John Gilmore fan. I read somewhere he played on percussionist Pete La Roca’s Turkish Women at the Bath:

I kept on the lookout for it. When I finally found it, I noticed it too was on the Douglas label and thought, “This is a label I need to pay attention to.”

This week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig in our paddles and explore the world of the Douglas Records.

After the failed launch of his first record company Duchess Records in Boston, Alan Douglas moved to New York where the French Barclay Records gave him his first big break in the record business. It was through this association that in 1960 when United Artists decided to start a jazz department, they hired Douglas to guide the venture. Within a few years, he had produced records for Art Blakey, Kenny Dorham, and Jackie McLean.

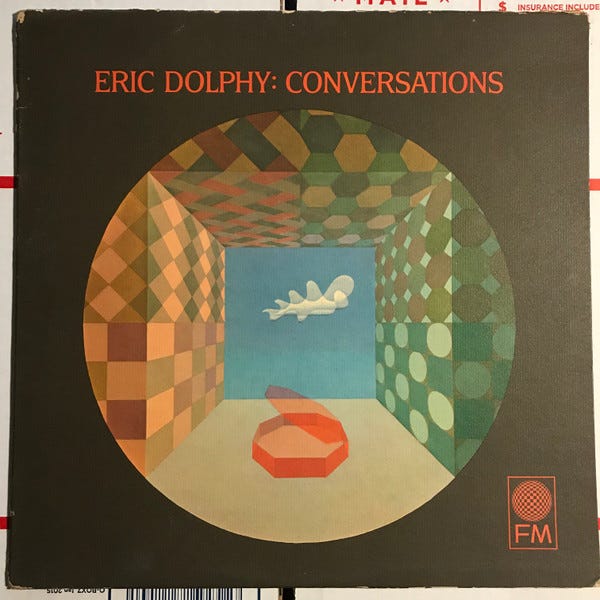

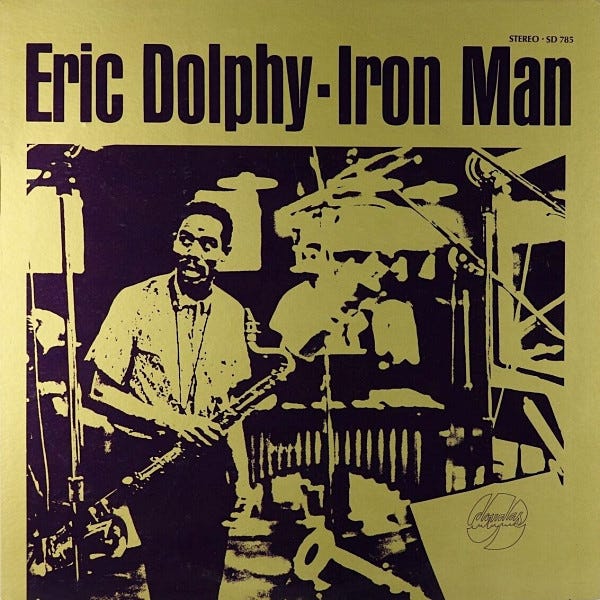

In 1964, United Artists asked Douglas to start a label to capture the new and growing audiences from the advent of FM radio. The label was called naturally FM Records. Douglas asked Eric Dolphy if he’d like to record with them, and he agreed - as long as he could play what he felt like doing. Douglas agreed and on July 1 and 3, 1963, he recorded the sessions that resulted in two albums: Conversations and Iron Man. It should be noted that these sessions were before Dolphy recorded his seminal Out To Lunch! for Blue Note Records.

Conversations was released in 1963:

From this album here is Jitterbug Waltz:

These sessions marked the recorded debut of eighteen-year-old trumpeter Woody Shaw. Bassist Eddie Khan also plays on this track. For more information about Eddie Khan, I wrote about him here:

Incidentally, Eddie Khan and Pete La Roca recorded on Joe Henderson’s classic 1963 Blue Note release Our Thing, Henderson’s second release as a leader. You can read more about La Roca here in a journey I wrote about Henderson:

Here’s another great track from Conversations, a duet with Dolphy and bassist Richard Davis:

The second record released from that session was Iron Man; however, these tracks were thought to be too progressive at the time and not released until 1968 on the Douglas International label:

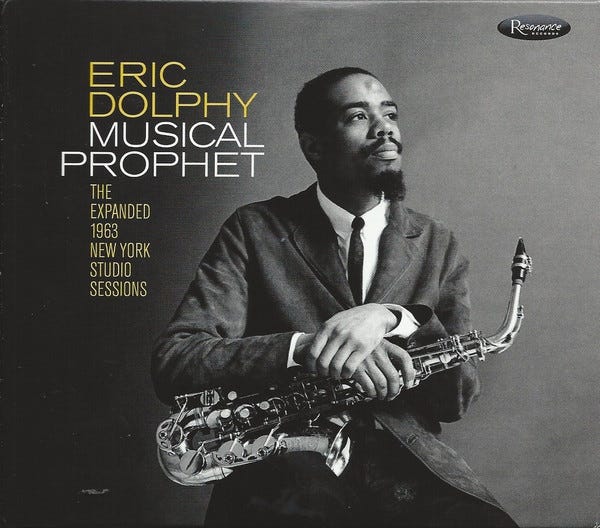

In 2019, Resonance Records released all the tracks from these sessions on Musical Prophet: The Expanded 1963 New York Studio Sessions:

FM Records went broke in 1965 and Douglas set out on his own. In 1967 he founded Douglas Communications, a platform that released records by jazz musicians, books by Lenny Bruce, Timothy Leary, and John Sinclair, and films directed by Mexican director Alejandro Jodorowsky.

One of Douglas Records’ first releases was La Roca’s Turkish Women at the Bath, which along with Gilmore also featured Chick Corea on piano. From that album here is the title track:

This was La Roca’s second album as a leader - the first was the excellent Basra released by Blue Note in 1965 with Joe Henderson on tenor.

In 1970, Douglas released the first album by The Last Poets, a radical group of black New York poets that hung out on the corner of 137th Street and Lennox Avenue. The album became a big hit. From that album, I like On the Subway:

Another song from the album is When the Revolution Comes, which inspired Gil Scott Heron’s response The Revolution Will Not Be Televised, first released on his 1970 album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox and then again in 1971 on Pieces of a Dream:

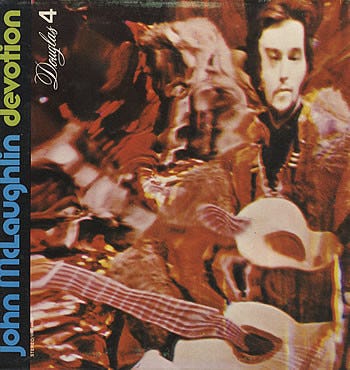

In 1971 Douglas released John McLaughlin’s masterpiece My Goal’s Beyond. Also in 1971, Douglas released McLaughlin’s Devotion, which is, for me, most remembered not for the music but for the album cover photo by Ira Cohen:

Between 1968 and 1971, in a loft on New York City’s Jefferson Street, poet, photographer, filmmaker, and self-styled electronic multimedia shaman Ira Cohen created some of the most mythic images of the late 1960s.

As the story goes, encouraged by his friend Allan Ehrlich, who had just started a business selling psychedelic posters, black lights, and rolls of Mylar reflective paper, Cohen began using the tape to make a series of alchemical photographic sessions in what he called his “Mylar chamber.” Cohen explains:

I put up these big sheets of Mylar and started to take some photographs, hamming it up by making faces or wearing costumes, just to see how it worked. I found that if there was a little ripple in it, you would suddenly get an image where all kinds of distortions happened, and if the distortion was powerful enough then that was a key. I was always looking for something harmonious, where a beautiful face could be somehow made more beautiful by the distorted changes in dimension reflected in the Mylar.

Here is a photo of Angus MacLise in the Mylar chamber, one of Cohen’s self-proclaimed masterpieces:

Cohen included copies of this photo printed in silver ink on white machine-made paper in Angus MacLise’s The Subliminal Report, published by Bardo Matrix in 1975. I wrote about Bardo Matrix here.

In 1968, when Cohen gained access to a Bolex movie camera, his dream of extending the Mylar chamber experience into film became a reality with The Invasion Of Thunderbolt Pagoda. You can watch the film here with music by Angus and Hatty MacLise and company:

Here’s one more for the road. Alan Douglas had a knack for bringing artists together. Perhaps none of his collaborations was as interesting as in 1962 for Money Jungle, a trio album with Duke Ellington playing with younger stars Charles Mingus on bass and Max Roach on drums. From that album, here is Fleurette Africaine (African Flower):

Although Douglas Records burned quickly, it burned brightly. Alan Douglas’ underground symphony documented an important time in American culture and inspired many future artists. For example, bassist and record producer Bill Laswell called Douglas “one of the most creative labels from that period.” He credits Alan Douglas’ creative force and energy, along with support from Island Records founder Chris Blackwell, for inspiring him to form the Axiom label in 1990, which in 1992 released The Master Musicians of Jajouka’s classic Apocalypse Across the Sky, which I wrote about here.

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of Bernard Herrmann.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel so inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

Money Jungle is one of my favorite albums, and that pete LaRoca record is another great obscure recording. I didn’t realize all these albums were connected to Alan Douglas.

Looking forward to your Herrmann piece!

In fairness, it might be worth mentioning that Douglas was very much a controversial figure,not least with the Hendrix estate due his involvement in releasing those horrendous " manufactured" Hendrix albums after the guitarists death. His mixing of Devotion in John McLaughlin's absence was another example.The English guitarist was not pleased with the results, saying it destroyed the album.