Count Basie - the early years

From spirituals to swing....

There is a passage in Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises in which a character named Mike is asked how he went bankrupt. “Two ways,” he answers. “Gradually, then suddenly.” This reminds me of how Bill Basie from Red Bank, New Jersey became the father of Kansas City Jazz and the leader of the great Count Basie Orchestra - gradually, and then suddenly.

I can still remember the first 78rpm record I ever bought - Bill Murray’s 1919 Victor You’d Be Surprised.

In the mid-1970s, when I was in 6th or 7th grade, my buddy and I rode our bikes over to an estate sale on the other side of White Bear Lake. Down in the basement of the house, we found a stack of strange, old records - 78rpm records. I picked this one out of a stack of hundreds because the tune was written by Irving Berlin, who I knew wrote the music for Fred Astaire’s 1935 movie Top Hat. I carried it home in one hand like a football as we rode our bikes back home. I played it on our stereo, and it reminded my of The Great Gatsby. The next weekend, I rode back over to the estate sale and bought some Al Jolson and Maurice Chevalier 78s.

Strangely, I didn’t start buying 78rpm records again until some 40 years later - first out of some nostalgic longing and then as a devoted collector. There’s something about holding an old pre-war 78rpm record. If it’s the 1936 Vocalion Jones-Smith Incorporated Lady Be Good, Lester Young’s first recording, it’s priceless. This was actually the Count Basie Quintet, but Basie was already under contract with the Decca label. Lester had just joined Bill Basie’s band before they went up to Chicago for that first recording session.

As a teenager in early 1920s New Jersey, Bill Basie had been a protégé of the great Fats Waller. He literally sat at Waller’s feet, observing him work the organ pedals in the pit of New York’s Lincoln Theater. During this time, Basie began playing the piano. He played the “stride” style - developed out of ragtime it was a quite formal and metronomic approach to piano popular at that time. The blues, which Basie would later learn from the Southwestern musicians and for which Basie would later become known for, had not yet penetrated black popular music of New York and the Northeast.

Before he was out of his teens, Basie was already touring as a professional pianist on the TOBA circuit with Gonzelle White and Her Big Jazz Jamboree vaudeville show. In the show, Basie played piano and a villain in a skit. In the streets, he also conducted what they used to call a “ballyhoo” to drum up interest in the show. However, in Kansas City in 1927, the show hit rock bottom. Stranded, Basie got a job as the accompanist for silent movies at the Eblon Theater.

While in Kansas City, Basie first made contact with the Oklahoma City Blue Devils, whose blues-inflected music had such a dramatic effect on him. Basie recalled fondly in his autobiography, “You just couldn’t help wishing you were part of it.”

Within a year, Basie had landed a job with the Blue Devils and when the Blue Devils dried up, he joined with Bennie Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra. Then, in April 1935, when Moten suddenly died, the victim of a surgical mishap during a routine operation, Basie took on a leadership role and secured a job at Kansas City’s Reno Club. While at the Reno club, Basie gradually gathered a little band of Blue Devils and Moten musicians around him and the rest is history….

Reno Club

In his autobiography, Basie recalled this about the Reno Club:

“...As long as I had been around Kansas City, I actually didn't know anything about (downtown). I had spent most of my time either on Eighteenth Street or Twelfth Street or down throughout in there.... Downtown Kansas City didn't mean anything to me. All of the real action was right where I already was.

“...Then I got my chance to go into the Reno Club all the way...at Twelfth and Cherry.... Somebody else was playing there, and he wanted to go somewhere for a few days...and asked me if I'd like to fill in for him.... I needed the job, and by that time I was curious about what it would be like to work in that part of town for a change....

“The manager of the Reno was a short little fellow named Sol Steibold, and we got along fine from the very beginning.... After I had been substituting in there for about a week, Sol...asked me if I would like to have the job on a permanent basis.... When I asked him about (the other pianist), he just shrugged his shoulders (and said,) ‘It’s your job if you want it.’

“...I started bringing in some of my old bandmates.... Since it was my band, naturally I wanted some guys down there that I was already used to playing with and who I also thought were the greatest....

“The Reno was not one of those big fancy places where you go in and go downstairs and all that. It was like a club off the street. But once you got inside, it was a cabaret, with a little bandstand and a little space for a floor show, and with a bar up front, and there was also a little balcony in there. There were also girls available as dancing partners. It was a good place to work. I liked the atmosphere down there. There was always a lot of action because there were at least four other cabarets right there on that same block, and they all had live music and stayed open late.”

Basie’s great saxophonist Buster Smith remembers: “(The Reno) was nothin’ but a hole in the wall. Just mediocre people mostly went in there, a lot of the prostitutes and hustlers and thugs hung out down there. And the house was packed. They had a show down there we had to play. Dancers and comedians and things like that.”

While at the Reno, Basie began the process of building his band. He recalls, “Lips Page and Jimmy Rushing had stayed in Kansas City (after Bennie Moten’s death), but when they came down to the Reno, they came as singles…. Lips was also the master of ceremonies and entertainer, and he would sit in with the band, but he was not a regular member of the trumpet section…. Jimmy Rushing...got a job as a regular single feature and as a part of the floor show, and he was such a hit that he could have stayed in there as long as there was a Reno Club….

“After a while, I had three trumpets, three reeds and three rhythms. So we called it Three, Three and Three. There was no trombone in there at first. I couldn’t afford one at the time. As a matter of fact, I didn’t have but two trumpets, because Lips Page made it three. The other trumpets were Joe Keys, who had been in Bennie’s band, and Carl Smith, better known as Tatti, who had once been with the great Alphonso Trent band out of Dallas….”

While at the Reno, Basie’s band became the Barons of Rhythm. Soon an experimental radio station was formed in Kansas City and Basie and His Barons of Rhythm began regular broadcasts. During one broadcast, the announcer, in the manner of “Duke” Ellington and “Fatha” Hines, wanted to give Basie’s name some style and called him “Count”. The name stuck.

Experimental Radio

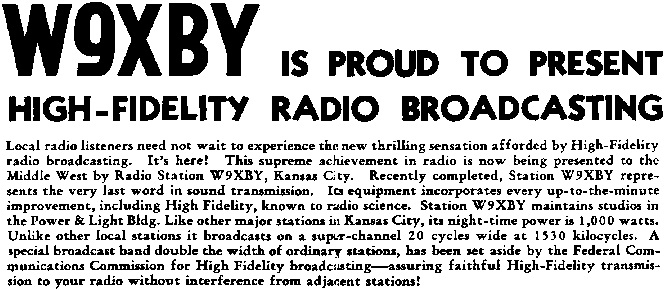

In late 1934, Kansas City was home to one of just four experimental high-fidelity AM stations in the United States.

On December 19, 1933, the Federal Radio Commission authorized three new broadcast-band channels above the previous upper bound of 1500 kHz. The three channels, at 1530, 1550, and 1570 kHz, were 20 kHz wide instead of the standard 10 kHz, thereby making high-fidelity broadcasting possible without interference from adjacent stations.

The Radio Commission assigned call letters to the four approved stations on May 25, 1934:

W1XBS, American-Republican, Waterbury, Connecticut

W9XBY, First National Television, Inc., Kansas City

W6XAI, Pioneer Mercantile Co., Bakersfield, California

W2XR, John V. L. Hogan, Long Island City, New York

In December 1934, W9XBY began operations.

In 1935, the tower for radio station W9XBY stood on the outskirts of Kansas City. From this tower, Count Basie and His Barons of Rhythm broadcast live from the Reno Club for a half hour six nights a week. Kansas City jazz was about to be discovered.

Here is how Basie’s Kansas City jazz sounded over the airways. This is Shoe Shine Boy recorded at their first recording session for Vocalion in 1936:

Hitting the big time…

On a clear night, the W9XBY signal could reach at least as far as Chicago, where record producer John Hammond heard them.

John Hammond tells about that night, “January of 1936, when I was out with Benny Goodman, I got so sick of listening to the same tunes every night that one night, I went out to my car and I went way to the end of the dial. I started to listen to some music from a band that I had not heard of, coming from the Reno Club in Kansas City. I couldn’t believe it. It was Count Basie and his orchestra….So I started writing Basie letters at the Reno Club. And I never heard a word.”

He decided to go on down to Kansas City to hear them for himself and recalls, “…I’ll never forget that first night I went to the (Reno). Basie had a show at eight o'clock...eight p.m. to four a.m. They did three shows a night. There were about four chorus girls, and there was a whorehouse upstairs, and Basie got eighteen dollars a week and the other guys got fifteen dollars a week….”

Count Basie also recalls that first meeting, “So finally, one night I looked up and John was sitting along side of me. That was really the first time that…we really ever got together, and we had a ball.”

Hammond invited Basie up to Chicago for his first recording session - the Vocalion Jones-Smith Incorporated session - and, by the end of 1936, the band moved from Kanas City to Chicago to start a long engagement at Chicago’s Grand Terrace Ballroom.

In 1937, the Basie band traveled from Chicago to New York City and took up residence at the Woodside Hotel in Harlem. He soon made his first record as the Count Basie Orchestra for the Decca label. Here is Honeysuckle Rose from that session:

The Count Basie Orchestra would finally hit the big time in December 1938 at John Hammond’s historic production From Spirituals to Swing performed at Carnegie Hall.

This was a highly ambitious and controversial concert documenting the history of “American Negro music, from spirituals to Swing” that spotlighted and celebrated the huge contribution Race Music played in popular American culture.

Intended as a tribute to Bessie Smith, who had died the previous year, the concert ended up being a memorial to Robert Johnson as well, who died shortly before coming to New York to appear as one of the featured acts. Hammond used Count Basie’s “Swing” Orchestra as the host band.

It had taken many years for that little band of Blue Devils and Moten musicians Basie gradually gathered around him to suddenly become the Count Basie Orchestra. After these early recordings, the Basie band would go on to follow its destiny, although it would still be two or three more years before it attained the fame we now associate with this iconic band.

Here’s one more for the road for Jeep up there in Vermont. Perhaps the tune Roseland Shuffle remains the archetypal example of what it was all about in the embryonic stage of the Basie orchestra, before it became one of the supreme American jazz big bands. Here is that song recorded in 1937 in New York City for the Decca label.

Next week, on that Big River Called Jazz, we’ll stay in New York City to explore trumpeter Frankie Newton and that kooky 1938 jazz experiment in Greenwich Village, Café Society.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button at the bottom of the page. Also, if you feel so inclined, become a subscriber to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe” button here:

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that….

Until then, keep on walking….