Wear it

Like a banner

For the proud--

Not like a shroud.

Wear it

Like a song

Soaring high--

Not moan or cry.

Color by Langston Hughes (from The Panther and The Lash)

Some time ago, the great record producer, Chuck Nessa, wrote this about Clifford Thornton, “My take is he was an interesting person/personality at the time with little musical consequence. Not a "dis" just an observation from someone living thru the era.” When I read it, I was struck by its frankness; however, I was also struck by its relative truth. It reminds me that Jazz is mostly made up of interesting and talented musicians who have had little musical consequence. Like all the arts, the superstars get the headlines, and the journeymen and journeywomen valiantly plug along waiting for the big break that never seems to happen.

In recent years, Clifford Thornton’s contribution to pan-African music and education has perhaps gained in consequence - even if it may be more historical and musical.

In his 1957 book Yallah, Paul Bowles wrote, “To lovers of the Sahara, its most fascinating inhabitants are the Touareg. There are obvious reasons for the interest they excite: they have chosen to live in one of the most distant and desolate regions of the world - the very center of the Sahara…. The Touareg were known as the ‘pirates of the desert’, and were hated and feared by everyone who had ever come within reach of their fast racing camels.”

I first read about the Touareg in Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky. Port’s wife Kit was kidnapped by them and held as a slave. Bowles’ description of the Touareg intrigued me. The second time I read about them was in his 1963 book, Their Heads Are Green and Their Hands Are Blue. In the chapter, The Baptism of Solitude, he describes the Touareg in a way that caught my attention again:

It is scarcely fair to refer to these proud people as Touareg. The word is a term of opprobrium meaning “lost souls,” given them by their traditional enemies the Arabs, but one which, in the outside world, has stuck. They call themselves imochagh, the free ones. Among all the Berber-speaking peoples, they are the only ones who have devised a way of writing their language. No one knows how long their alphabet has been in use, but it is a true phonetic alphabet, quite as well planned and logical as the Roman, with twenty-three simple and thirteen compound letters.

So, I knew about the Touareg before I noticed that they played on Archie Shepp’s BYG Actuel album Live at the Panafrican Festival, recorded in Algeria in July 1969. However, this album would be the first time I heard about Clifford Thornton.

The album opens with Brotherhood At Ketchaoua, in which Shepp, Thornton, and trombonist Grachan Moncur III play with Touareg and Algerian musicians in front of the Ketchaoua Mosque in Algiers’ Casbah:

Here is the entire album:

Incidentally, this album was engineered by French saxophonist Barney Wilen. You can read more about him here:

In 1961, after serving in U.S. Army bands in Korea and Japan, Clifford Thornton moved to the Williamsburg area of Brooklyn in an apartment building with other young musicians. He worked as a sideman for notable avant-garde jazz bands and in 1962 joined Sun Ra’s Arkestra. He performed on Sun Ra’s Art Forms on Dimensions Tomorrow:

In 1966, he recorded on another seminal album: ESP-Disk’s Marzette Watts and Company:

You can read more about Marzette Watts here:

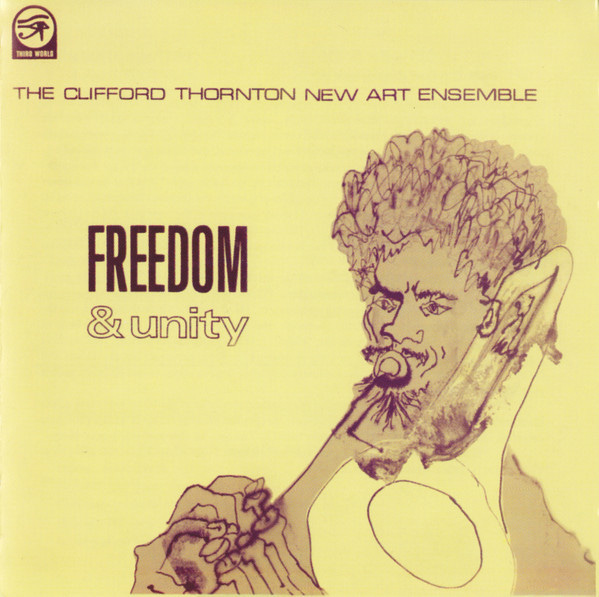

On July 22. 1967, Thornton recorded Freedom & Unity on his independent label Third World Records.

Recorded using a pianoless quintet and Karl Berger’s vibes, I find the album basically an extension of the work he did on Marzette Watts and Company. The album also features the debut of Joe McPhee on trumpet - sounding a lot like Ornette Coleman on trumpet.

However, Thornton’s music took a clear turn when he traveled with Archie Shepp to Algeria for the 1969 Pan-African Festival. The experience raised Thornton’s pan-African awareness, solidifying and invigorating his support for the nationalist revolutionary politics of the era. In his own words: “It was in Algiers, also in 1969, at the First Pan-African Cultural Festival (sponsored by the Organization of African Unity), that I made first-hand contact with this music on the ‘mother earth’.”

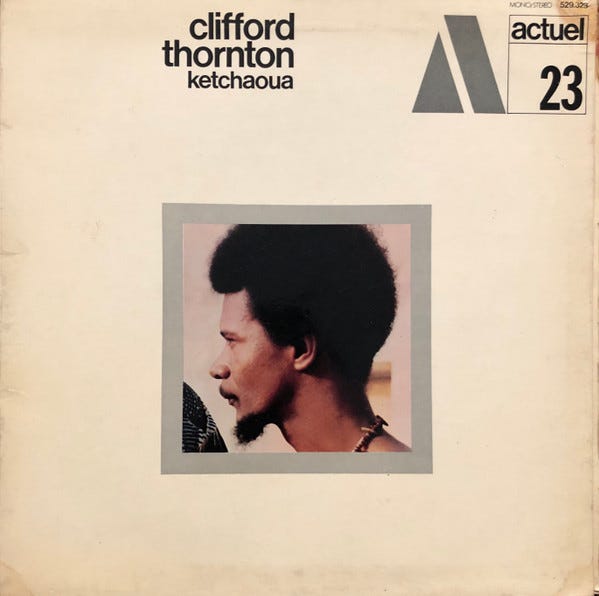

With the experience of the festival clearly still on his mind, he traveled to Paris and recorded Ketchaoua. He played cornet and congas on the album and is joined by saxophonists Arthur Jones and Archie Shepp, trombonist Grachan Moncur III, pianist Dave Burrell, bassists Beb Guérin and Earl Freeman, and drummers Sunny Murray and Claude Delcloo.

Here is the entire album - pay particular attention to the first two tracks:

On the BYG Records website, they state: “In many ways this introspective and even philosophical album immerses us in questioning, between dream and reality.” Although it never reaches the artistry or introspection of the Art Ensemble of Chicago’s People In Sorrow, recorded nearly a month earlier, the first side of Ketchaoua is compelling in its own way.

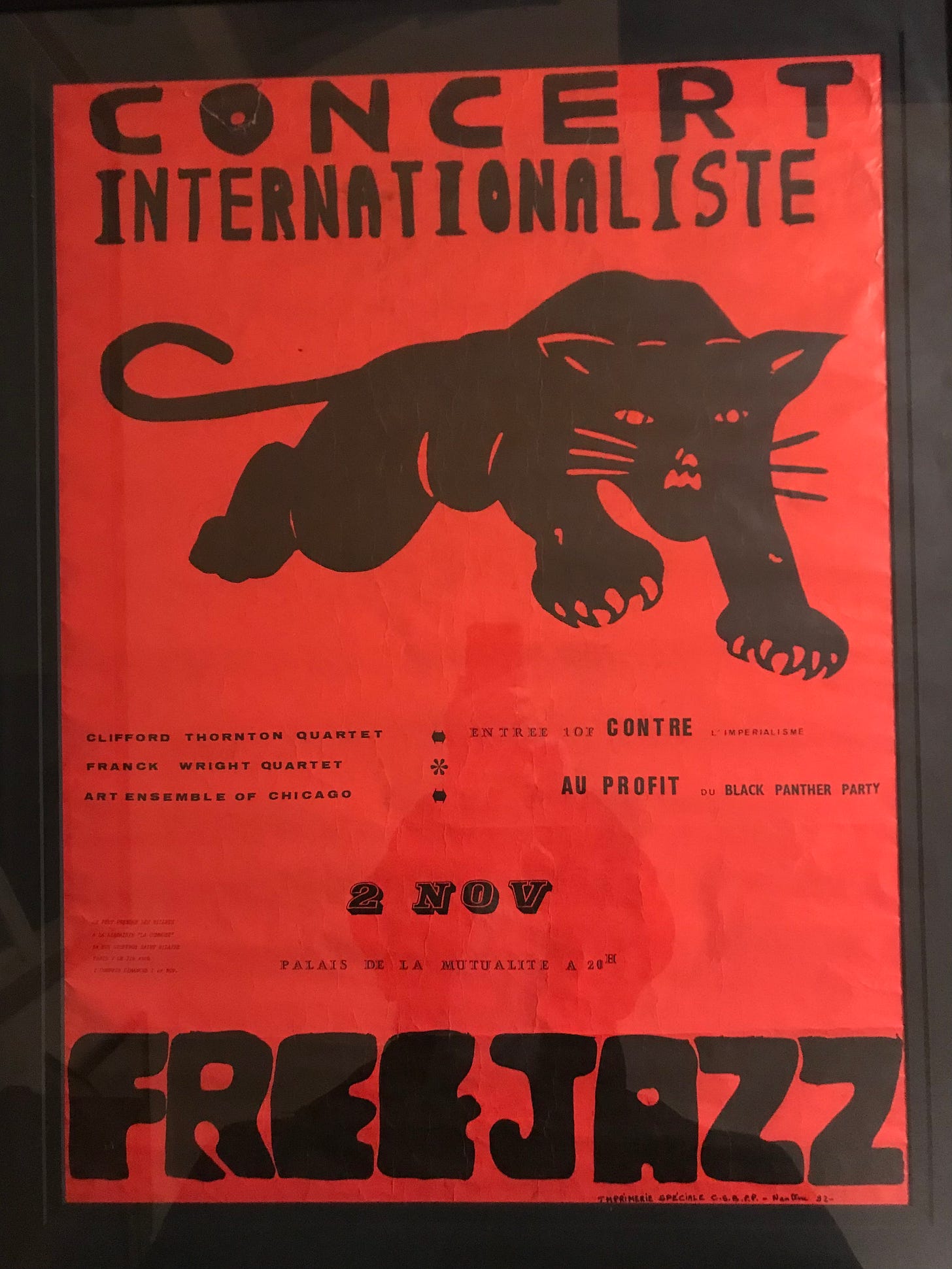

In 1970, Thornton briefly visited Ghana, Togo, Dahomey, Nigeria, and Cameroon, and performed in Tunisia before returning to Paris for a concert on November 2nd at the Palais de la Mutualité, organized as a benefit for the Black Panther Party. Here’s a poster from that concert:

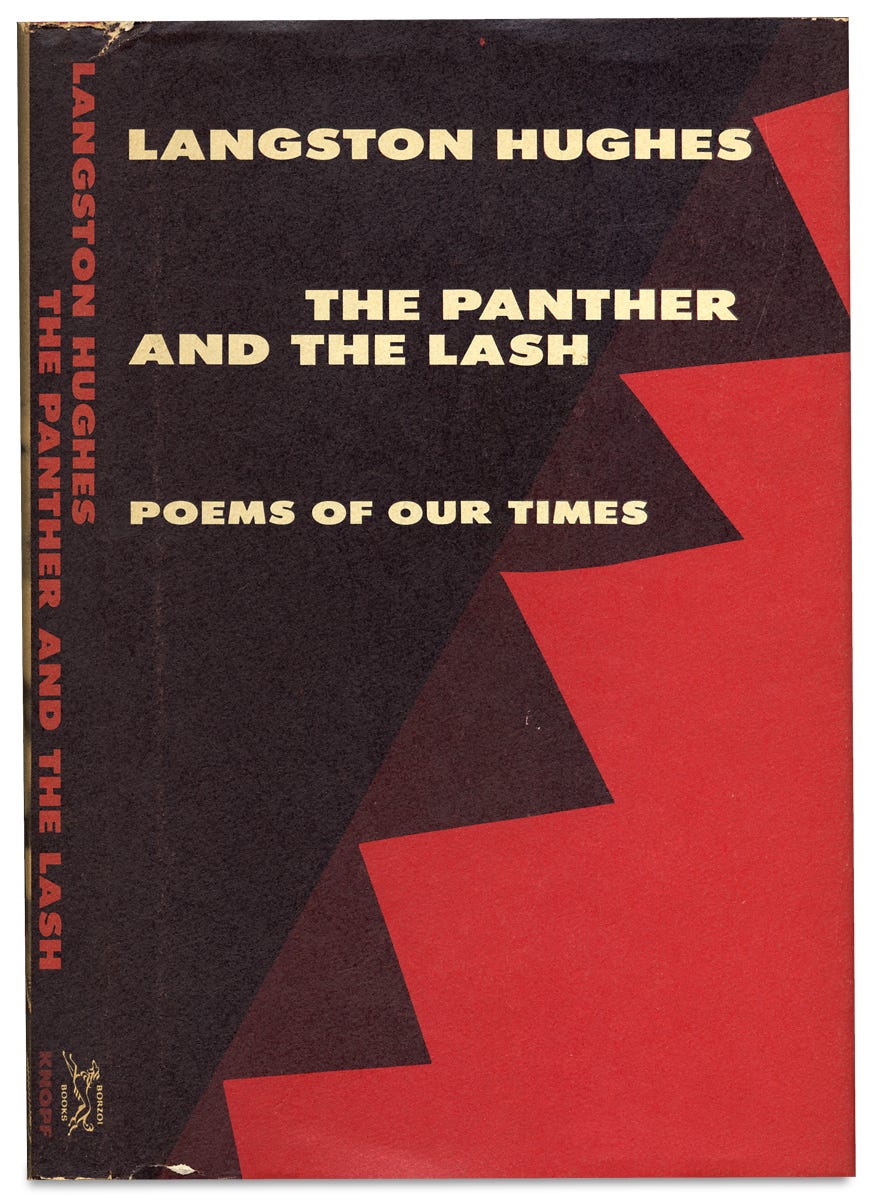

Five days after the concert, Thornton recorded The Panther and The Lash at La Maison de la Radio in Paris.

Thornton took the title of the album from Langston Hughes’ 1923 book of the same name - it was Hughes’ final book:

The book offers seventy poems reflecting “various aspects of the racial turmoil that has rocked this country in the last decade.”

Two of my favorite songs on The Panther and The Lash have their origins in Africa: Shango/Aba L’Ogun comes from the West Coast; and Mahiya Illa Zalab is a Tunisian folk song. Here is Shango/Aba L’Ogun:

French pianist François Tusques plays piano on this album. He is an artist worthy of more recognition, but we’ll discover him a little further downstream….

In 1968, jazz musician, composer, and educator Ken McIntyre recommended Thornton as a candidate for Assistant Professor in world music at Wesleyan University. He was hired in 1969 and his tenure ran through 1975. In 1976, Clifford accepted a position as an educational counselor on African-American education with UNESCO's International Bureau of Education and moved to Switzerland, where he spent his last 15 years. He died in relative obscurity in Geneva on November 25, 1983.

Although it may be true that Clifford Thornton’s mark on jazz may have had little musical consequence, I think his story and his music are still well worth telling. And his story is the story of most artists whose names never make it up on the marquee; however, they are all still important - consequential in their own ways. They all make up the waters that flow in that Big River called Jazz.

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles in to explore the waters of Oakland record label Black Jazz.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel so inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….