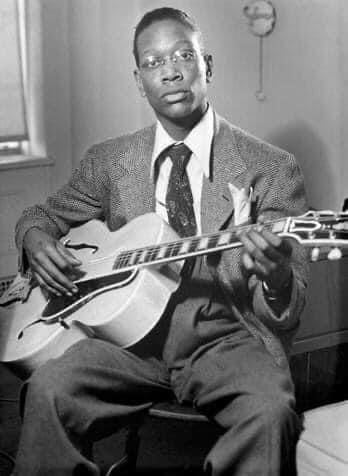

With Christian, the guitar found its jazz voice.

With his entry into the jazz circles, his musical intelligence was able to exert its influence upon his peers and to affect the course of the future development of jazz.

-Ralph Ellison

I have often thought about the odd way my jazz journey brought me to bebop. The more traditional journey would be to start with swing and then move into bebop and hard bop and then on to free jazz. However, for me, I was listening to the straight ahead Atlantic, Riverside, and Columbia jazz records discovered at “Ground Zero”, the hard bop of the 1980s Blue Note releases, and even Sun Ra’s live shows before I really ever listened to bebop. Then, many years later, I rediscovered the beauty of swing from 78rpm records that relatives passed on to me - in particular, my English uncle Ron had a very nice swing collection that my aunt Peg brought over to me from England. These records really brought me back full circle to the early Fred Astaire movie soundtracks I had watched on TV in elementary school - songs like The Carioca and Slap that Bass - that touched my heart.

So for me, the journey was actually more like: From Fred Astaire to hard bop to Sun Ra to bebop and then back to swing, if you know what I mean. An odd journey perhaps, but it was my journey.

I didn’t really listen to Charlie Parker until well after I had listened to Art Pepper, Dexter Gordon, Hank Mobley, and John Coltrane. I actually think I thought bebop was a little passé. But after hearing Frank Morgan playing with Cedar Walton’s trio in San Francisco in the late 1980s, I gained a new appreciation. It seems fitting that a fellow Minnesotan, Frank Morgan, would have a big hand in my discovery of bebop. I fondly recall after all his shows, he lifted his alto and with that big smile would say: “Bebop Lives!”

Frank Morgan was born in Minneapolis in 1933. He was the son of Harlan Leonard of the Ink Spots. When he was seven years old he met Charlie Parker after a Jay McShann gig at the Paradise Theater in Detroit, Michigan. The following day they met at a music store and Parker got young Frank started playing the clarinet. He soon moved to the soprano and then onto his signature alto sax, like his hero. For more information about the life and times of Frank Morgan, you can read about it here:

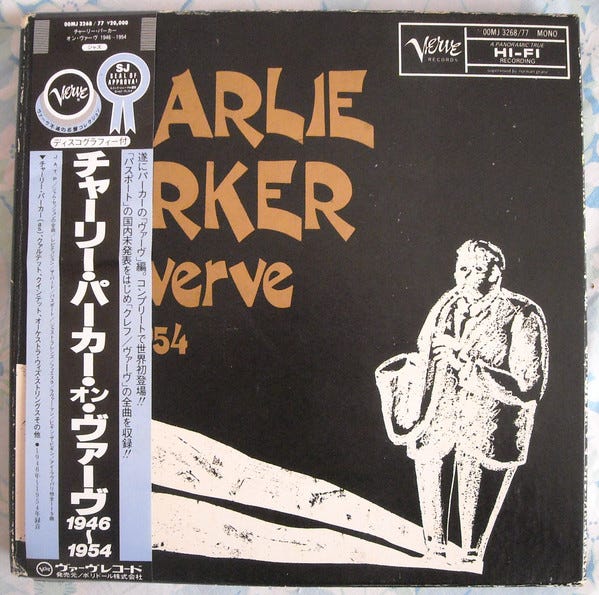

In 1988, while I was living in Cupertino, there was a lot of press about Frank Morgan’s musical comeback, after some 30 years in and out of prison. In 1985, he recorded Easy Living for Contemporary Records, his first album as a leader in 30 years. It was an unbelievable comeback. In 1986, he followed it up with Lament and Bebop Lives! Then, in 1988, at about the time I was seeing him with the Cedar Walton trio up and down the Bay Area from Santa Cruz to Oakland, he released Yardbird Suite. By then, I was starting to dig bebop more and bought this Charlie Parker box set.

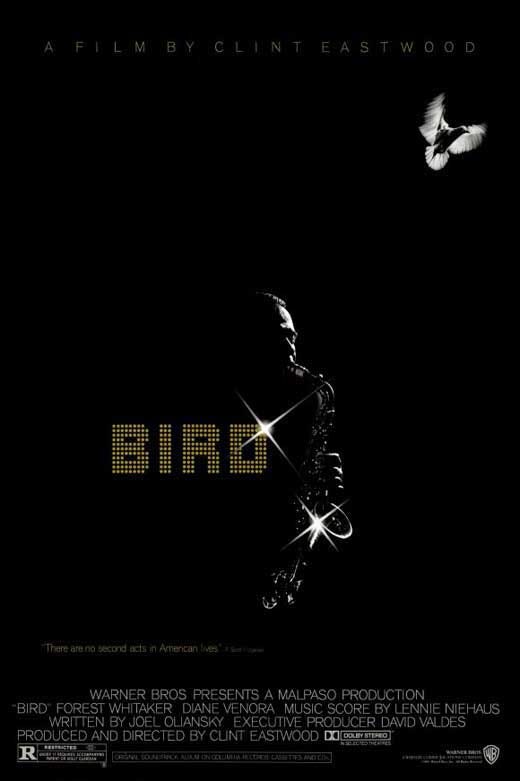

Also in 1988, Clint Eastwood’s movie Bird was released, starring Forest Whitaker.

This is really when I started to discover the music played in Minton’s Playhouse by Charlie Christian and the gang - the music that moved swing to bebop….

According to Wayne Goins and Craig McKinney in their book A Biography of Charlie Christian: Jazz Guitar's King of Swing, Charlie Christian was born in Bonham, Texas in 1916. In 1918, the musically gifted Christian family moved to Oklahoma and settled in the Deep Deuce area of Oklahoma City.

“The Deep Deuce is a working laboratory where [Christian] can hear the musicians coming through and play with them,” said Hugh Foley, professor of fine arts at Oklahoma’s Rogers State University. “Since he was a kid, he’s had constant on-the-job training.”

Charlie Christian’s early inspirations came from his creative family. His blind father was a singer, trumpet player, and guitarist, and his mother played piano. His two brothers, Clarence and Edward, also were musicians. Edward was once a member of the Blue Devils, the prominent Oklahoma City jazz group.

When their father was struck blind by fever, in order to support the family, he and the boys would work as buskers, on what the Christian’s called "busts." He would have them lead him into the better neighborhoods where they would perform for cash or goods. When Charlie was old enough to go along, he first entertained by dancing.

After his father died, Christian took up the guitar and achieved local fame performing with Anna Mae Winburn’s Cotton Club Boys and Al Trent’s sextet locally and throughout the Midwest, as far North as Minnesota and North Dakota. By 1936, he started jamming with major performers traveling through Oklahoma City, including Teddy Wilson, Art Tatum, and Andy Kirk. The Blue Devils and Western swing kings Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, which Christian listened to on the radio, were especially influential in shaping Christian’s music. Jazz artists from around the country came to Oklahoma City. Among them was saxophonist Lester Young in 1929, who Ellison recalled as “perhaps the most stimulating influence upon Christian.”

Charlie Christian’s big break came when John Hammond heard about him through Kansas City pianist Mary Lou Williams and set up an audition with Benny Goodman in Los Angeles. I like how Stanford University’s Riverwalk Jazz describes the meeting:

On August 10th, 1939 the ‘King of Swing’ Benny Goodman was in a Los Angeles recording studio making his debut sides for Columbia Records. A young black guitar player walked in the door. Producer John Hammond described him as "a scared kid," wearing "a broad-brimmed Texas hat, very pointed yellow shoes, a green suit and a purple shirt." His name was Charlie Christian, 23 years old and fresh off the plane from his hometown, Oklahoma City. He had a guitar case in one hand and an amplifier in the other.

Classic. On first sight Goodman was not impressed with Christian, but later that night he couldn’t resist giving him a gig. John Hammond engineered a surprise audition for Christian on stage at Goodman’s club date. Irked to see the new guitarist on stage with him, Goodman signaled Christian to take a solo on “Rose Room”—thinking he would embarrass this ‘scared kid’ from Oklahoma. Charlie Christian’s spectacular solo stopped the show and the Benny Goodman Sextet was born.

Although Charlie Christian’s first recording was with Lionel Hampton and his Orchestra for Victor in September 1939, his guitar was used as the more traditional rhythm instrument. This is One Sweet Letter To You, one of my favorites from that session and features a few choice Christian licks in the middle.

To his credit, it was Benny Goodman, in the seminal Columbia recordings in October and November of 1939, who allowed Christian to use the electric guitar as a front line solo instrument. Here’s a more typical song from that earlier Benny Goodman Sextet, Seven Come Eleven, recorded in New York City on November 22, 1939, featuring Fletcher Henderson on piano, Lionel Hampton on vibes, Nick Fatool on bass and Artie Bernstein on drums.

As well as playing guitar for Benny Goodman, Christian participated in after hours jam sessions with other musicians in places such as Minton’s Playhouse and Monroe’s in New York City. On 12 May 1941, Christian played Swing to Bop at Minton’s, with Joe Guy on trumpet, Kenny Kersey on piano, Nick Fenton on bass, and Kenny Clarke on drums.

Without the time constraints inherent to 10” 78rpm records, live track recordings give us an idea of the longer solos Christian typically played in Goodman’s sextet that showcased his incredible improvisational skills. It is with recordings like these that we hear musicians, like Christian, doing what came naturally. They played what they had been playing pretty much their whole lives, but would be branded as a new music and given the name bebop. Here is Swing To Bop, with the new sound that would influence guitarists for years to come:

During the time Christian was jamming at Minton’s and recording with Benny Goodman’s Orchestra and Sextet, he also found time to record outside the Goodman band.

For example, I really like Christian’s acoustic guitar work on Profoundly Blue No. 2 with Edmond Hall’s Celeste Quartet, recorded in February 1941 for Blue Note. This was Christian’s only Blue Note session:

The terrific but short-lived Goodman Sextet came to an end in June 1941, when illness forced Christian out of the band. Less than a year later on March 1942, he died of tuberculosis. He was only 25 year old.

In a nice article about Charlie Christian from his website Swing & Beyond, I think Michael P. Zirpolo puts it best:

“It is difficult to overstate how important the Benny Goodman Sextet recordings featuring Charlie Christian were to beginning the process of the use of the electric guitar in jazz, popular music, and ultimately rock, where it is ubiquitous. Charlie Christian was the pioneer on that instrument, possessed of the right skills at the right time before the right people. He made the most of the opportunity presented to him by John Hammond and especially by Benny Goodman, and American music is richer because of that.”

Here’s one more for the road, On The Alamo, recorded for Columbia in NYC in January 1941. This is perhaps my favorite of all the Goodman Sextet sides with Christian:

Next week, On that Big River called Jazz, we’ll journey through the music of Bill Evans.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button at the bottom of the page. Also, if you feel so inclined, become a subscriber to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe” button here:

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

The various 1941 after hours recordings featuring Charlie Christian and Thelonious Monk were where I got my beginnings in more extensive jazz listening beyond a few stray tunes now and then. With some exceptions, I have been taking a more historically focused path back from that point in time.