My feelings and yearnings are those of a composer of the 19th century. I am completely out of step with the present.

-Bernard Herrmann in a letter to his wife

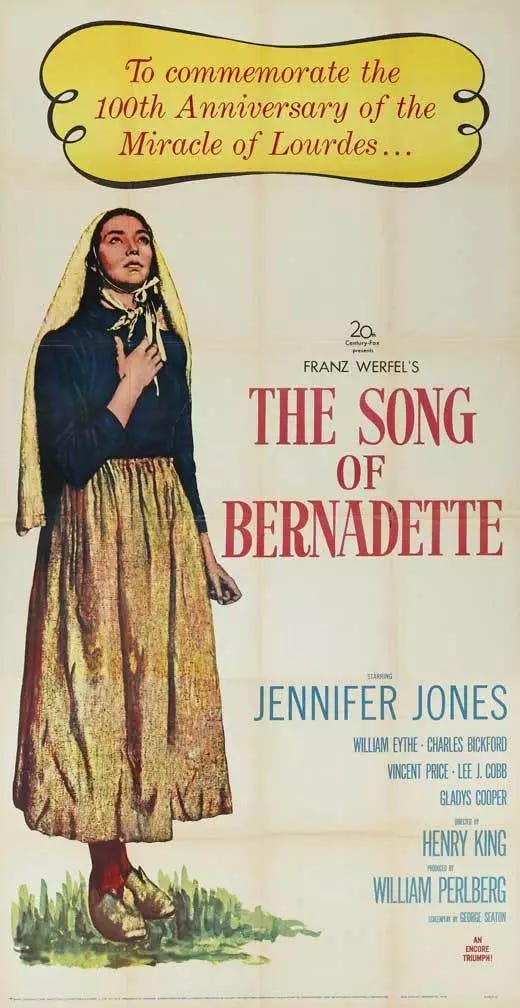

When I was in junior high school, I watched a movie in my basement that captured my heart. It was Henry King’s 1943 film The Song of Bernadette starring Jennifer Jones, which earned her the Academy Award for Best Actress:

I re-watched The Song of Bernadette the other day for the first time in nearly 50 years. It captured my heart again but for a different reason. The first time my attention was squarely on Bernadette’s suffering; however, this time I watched from the perspective of Bernadette’s parents and ultimately their suffering while she was dying in the convent at Nevers. With not even three months since my son passed away, their suffering was understandable to me, and nothing I can write gives any idea of it.

The Song of Bernadette is a remarkable film. It’s based on the 1941 novel of the same name by Austrian-Bohemian novelist Franz Werfel, who was born in 1890 in Prague then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. With the outbreak of World War I, he served in the Austro-Hungarian Army on the Russian front. After the war, he and his wife journeyed to British-ruled Palestine and encountered an Armenian refugee community in Jerusalem that inspired his novel The Forty Days of Musa Dagh. The novel was published in Germany in November 1933 and achieved international success. It is also credited with awakening the world to the persecution and genocide inflicted on the Armenian nation during World War I.

With the rise of the Nazi party, Werfel was forced to leave his position at the Prussian Academy of Arts, and his books were burned. He and his wife left Austria after the Anschluss in 1938 and went to France, where they lived in a fishing village near Marseille.

Fleeing for their lives before the Nazi invasion of France in 1940, the Werfels took refuge in Lourdes. While in hiding, Franz became interested in the history of Bernadette Soubirous - Our Lady of Lourdes. While he was there, he made a vow:

…if I escaped from this desperate situation and reached the saving shores of America, I would put off all other tasks and sing, as best I could, the song of Bernadette.

American journalist Varian Fry’s Emergency Rescue Committee, which also helped artists Hannah Arendt, Marcel Duchamp, Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, and André Breton escape persecution, organized for the Werfels a secret crossing over the Pyrenees on foot. They were then sent to Madrid and traveled to Portugal. They stayed in Monte Estoril, at the Grande Hotel D'Itália. On October 4, 1940, they checked out and boarded the S.S. Nea Hellas headed for New York City. They arrived on October 13th and eventually settled in Los Angeles, where they met other German and Austrian emigrants, including Arnold Schoenberg.

California and Los Angeles in the 1930s were very different from how they are today, and, apart from the hub of Hollywood, they seemed provincial compared to the East Coast. But opportunities were there and the relatively low cost of living attracted many Central European refugees from Nazism, many of them important artists. By 1942, European exiled artists in LA included, among others, Werfel, Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, Darius Milhaud, Thomas Mann, Bertolt Brecht, and Hanns Eisler. Although not a European refugee, composer Bernard Herrmann was there too.

This week on that Big River called Jazz we dig in our paddles and explore the world of Bernard Herrmann.

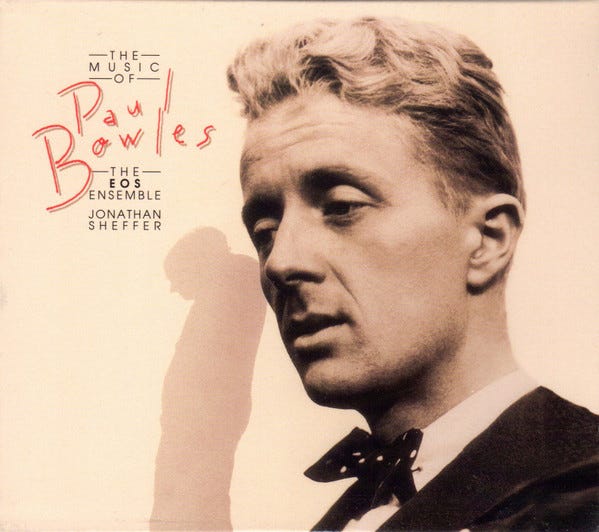

I first started following the Eos Ensemble in 1996 when they released the terrific The Music of Paul Bowles:

The Eos Ensemble made its debut in two sold-out concerts featuring the music of Paul Bowles at Lincoln Center in September 1995 and this CD was released as part of that program. From CD here is the beautiful Caminata from Pastorela: First Suite (1947):

…and Secret Words, a song Bowles wrote in 1943 and dedicated to his close friend composer Peggy Glanville-Hicks.

In 2001, in either Chicago or New York City - I can’t recall now - I saw the Eos Ensemble performing a concert of Schoenberg music combined with songs from Hitchcock movies composed by Bernard Herrmann. Although I had seen all the Hitchcock movies that Herrmann scored, I never knew who he was until that 2001 Eos Ensemble performance.

Bernard Hermann was born in New York City in 1911, the son of a Jewish middle-class family of Russian origin. After winning a composition prize at the age of thirteen, he studied music at New York University and also studied at the Juilliard School. At the age of 20, he formed the New Chamber Orchestra of New York and wrote his first dramatic score at the age of 22. In 1934, the aspiring composer, an active member of Aaron Copeland’s circle, joined the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) as a staff conductor.

At CBS, he met Orson Welles and wrote and arranged scores for radio shows in which Welles appeared, like the Columbia Workshop and two radio shows for adaptations of literature and film: Welles's Mercury Theatre on the Air; and Campbell Playhouse series (1938–1940). In a February 1938 Columbia Workshop - you can hear the entire workshop here - Hermann recorded John Keats’ La Belle Dame sans Merci - and with this performance, Herrmann hit the big time:

I first heard the music of Bernard Herrmann in grade school on a War of the Worlds radio show bootleg cassette tape. I bought it from a guy selling them in the ads section at the back of Liberty Magazine - of course, the music was just background noise and I had no idea who Herrmann was.

The cassette looked kind of like this, but even older and more do-it-yourself:

I played that tape on the tape recorder I wrote about on this journey:

Pierre Mariétan

I’ve been paddling hard for two years on that Big River called Jazz. It’s time to portage my canoe and take a walk in the field to areas of music not really part of the Jazz world, but still dear to me: field recording and musique concrète….

When I listened to that tape probably in 1974, this is what that show sounded like with noise in the background by the fictional conductor “Ramón Raquello”:

“Ramón Raquello” was Bernard Herrmann conducting a live performance for the broadcast, which aired on the CBS Radio Network’s series The Mercury Theatre on the Air on Halloween October 30, 1938.

Here’s a photo from that night, with Herrmann conducting behind Welles, who has his arms raised:

In 1939, when Welles signed his RKO Pictures contract in Hollywood, Herrmann worked for him and in 1941 wrote the score for Welles's first film Citizen Kane, which earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Score of a Dramatic Picture.

Years later, Herrmann was closely associated with director Alfred Hitchcock. He wrote the scores for seven Hitchcock films, from The Trouble with Harry (1955) to Marnie (1964), a period that included Vertigo, North by Northwest, and Psycho. I particularly like the score for Vertigo.

When I first met my wife in Chicago, her girlfriend worked at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO). At the time Daniel Barenboim was the CSO’s music director. She gave me a CD of Barenboim conducting the CSO’s performance of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Admittedly, I had zero interest in Opera then and no intention of playing it. As it turns out, probably ten years later, after reading about the opera I decided to play it. From the start, I was blown away.

Recently, in a strange coincidence, I learned that Herrmann’s leitmotif for the romantic song Scene d'Amour from Vertigo was based on Wagner's Liebestod (Love-Death) from Tristan und Isolde. Here is Waltraud Meier performing it with Barenboim conducting:

For some background on the significance of this, listen to Stephen Fry’s fascinating analysis.

Compare Wagner's Liebestod to Herrmann’s Scene d'Amour:

Brilliant. Like Wagner, Herrmann’s scores, as Fry says, “…keeps you on the edge of your seat.”

Herrmann was also known for using electronic instruments in his scores, including the theremin, electric strings, electronic organs, and the Moog synthesizer. Early in the production of The Birds, Hitchcock decided it would have no conventional music score, and so Herrmann is credited as Sound Consultant. This meant working with Oskar Sala and Remi Gassmann experts on the electro-acoustic Trautonium - the cries of the birds that punctuate the latter part of the film were created on the machine by Sala in West Berlin.

I wrote a little about Hitchcock’s The Birds here:

Had Bernard Herrmann only written the scores for Hitchcock movies his place in history would still be secure; however, he continued to write amazing scores like this one for Fahrenheit 451, the 1966 British dystopian drama film directed by François Truffaut:

…and for Brian De Palma’s 1976 American neo-noir psychological thriller film Obsession:

In 1992 Joshua Waletzky directed the documentary film Music for the Movies: Bernard Herrmann, which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature:

Here’s one more for the road. Bernard Herrmann died on Christmas Eve 1975, only hours after completing the final recording session for Martin Scorsese's 1976 film The Taxi Driver, which earned Herrmann a posthumous Oscar nomination for Best Score.

The alto soloist on the original movie score was Ronnie Lang, however; he was unavailable for the later soundtrack recording, which is played by Tom Scott. I prefer Lang’s version:

Given its heavy reliance on the jazz idiom, The Taxi Driver is an unusual score for the classically trained Herrmann, who once expressed a skepticism bordering on distaste for the use of jazz in film. Interestingly, I find this his best score.

From Citizen Kane to The Taxi Driver, Bernard Herrmann had spent the last 35 years of his career honing his genius for writing film scores of dark power, often employing unusual instrumental combinations. I have to admit for someone who has always been a big fan of European soundtrack composers like Ennio Morricone and Piero Umiliani, I’m a little disappointed that it took me so long to appreciate the scores of American Bernard Herrmann, the maestro of the macabre.

Next week, on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles in and explore the world of Terry Jennings.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

What a fantastic post. I love Hermann, Morricone, James Bernard (Hammer) & Carl Stallings. The list of exiles living in 1942 Los Angeles is hard to fathom.

Thanks for another great post.