My growth, my aliveness, happens through my ear. As I tune myself up through that instrument - because it's got so many wonderful stories to tell me - then I really see my road in front of me, in terms of realizing the instrument. I get a very clear and solid picture of where I'm at, any time I want to check it out, from playing my instrument

-Barre Phillips

In high school in the late 1970s, while I did my homework, I listened to a local jazz station on the radio. They played almost entirely what the DJs called “smooth jazz” - the only jazz I knew existed then. So I heard a lot of Weather Report, Spyro Gyra, Grover Washington, Jr., and Bob James. I recall liking songs from Bob James’ albums One On One with Earl Klugh and Lucky Seven, both recorded and released in 1979.

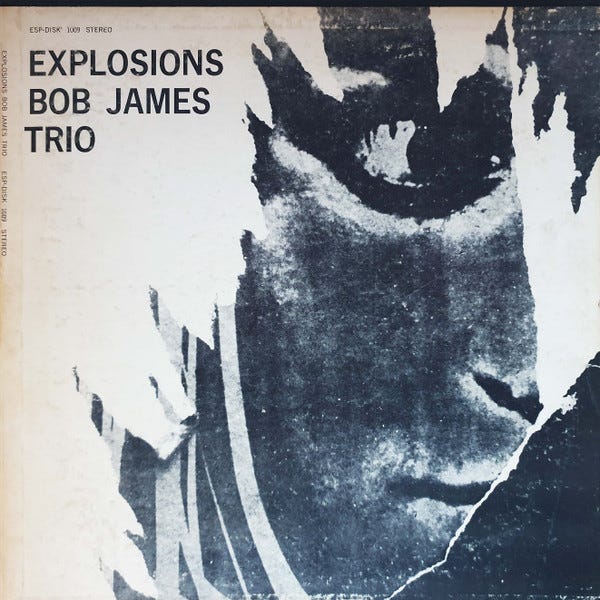

By the 1990s, I had moved on to heavier free jazz stuff and collected albums from labels like BYG Records’ Actuel Series and ESP. When I came across ESP’s Bob James Trio album Explosions, I couldn’t believe it was the same Bob James - there must be two.

From that album, here is Peasant Boy:

Explosions was recorded in 1965 at Bell Sound Studios in New York City, so it never occurred to me that he could have started as a free jazz musician. Well, I was wrong. It was the same Bob James, just playing a far cry from what I heard on One on One.

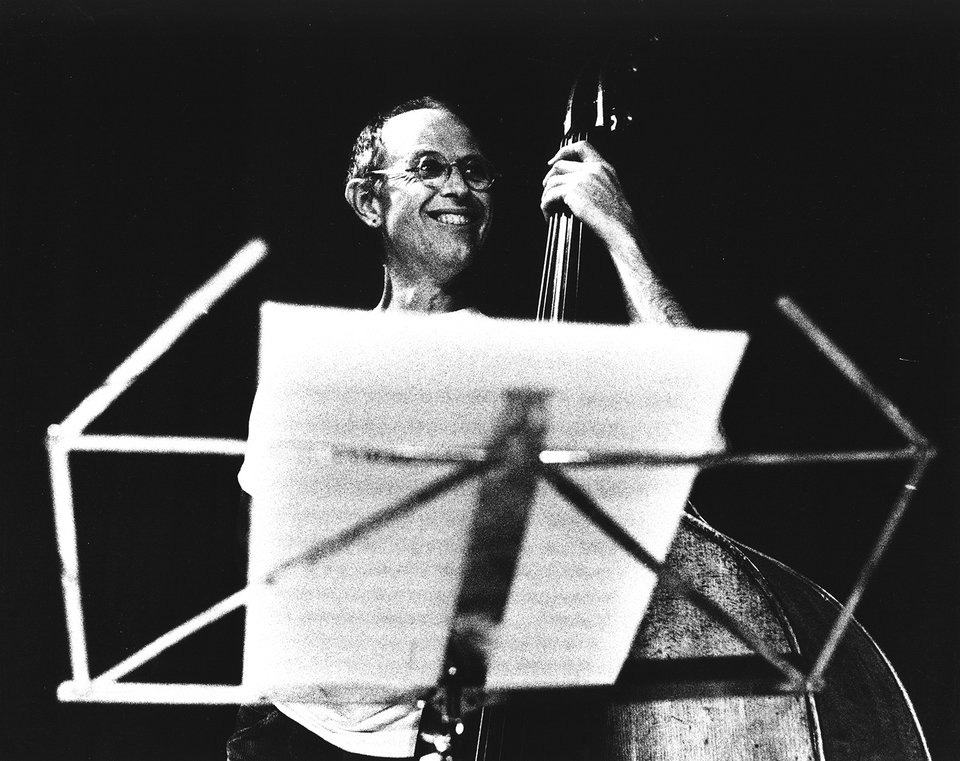

The bassist on Explosions is the late Barre Phillips, who passed away on December 28, 2024. He was 90 years old. Phillips was one of the most influential bassists of his generation. He was a true jazz pioneer and lifted the instrument to new levels of flexibility and expression.

This week on that Big River called Jazz, our journey is dedicated to the world of Barre Phillips.

Barre Phillips was born in San Francisco on October 27, 1934. When he was one year old, his family moved to southern Oregon, where he grew up. In junior high school, his family moved to Palo Alto, California, where he started playing bass. He played in the school's symphony orchestra. Later, he played Dixieland jazz in his brother’s band.

Self-taught for the first 15 years, he followed the typical jazz progression, moving from Dixieland into bebop and right into the mainstream jazz of the 1950s. He attended the University of California at Berkeley and formed a quartet. However, an early meeting with Ornette Coleman marked the beginning of a change he was feeling about his musical journey. In a 2000 interview, Phillips described Coleman’s impact:

It wasn't so much the music, which I loved very much. It wasn't a big discovery, the music itself. It was what he was talking. It was what he was saying with his words when you would talk with Ornette because I met Ornette in 1958, I mean, personally. It was actually four years later when I re-met him after he had made all those initial records and everything. I met him again and he gave me the message...

He came and sat in with a band that I was playing with out in California. He had been in New York for about four years at that time. He was out on the West Coast again. I was still on the West Coast and he sat in with us on a friendly basis. We were just playing standards and what was acceptable in the jazz repertoire at the time and he said, "Well, you guys played great. How come you're playing this school music? Why don't you play your own music?" And I was ready for the message.

Soon after that meeting, in 1962, Phillips moved to New York City.

It was a historical moment in New York and the contemporary music scene. He met Don Ellis very quickly and joined his experimental workshop, where he first started composing abstract music. However, there was very little work for this new music.

In 1964, he traveled to Europe for the first time with the George Russell Sextet - the first year American avant-garde jazz traveled to Europe in an official tour. In early 1965, he toured Europe again, this time with Jimmy Giuffre’s old Free Fall trio. However, it was an August 1967 trip to London when Phillips’ career took off.

The following year, he made a seminal recording at the Parish Church of St. James' Norlands in Notting Hill. The recording was set up by Max Schubel, whom he had met earlier in New York City. Schubel was in London to explore and record electronic music media with the intent of starting a new record label. Schubel approached Phillips to record source material for him to take into an electronic studio and compose with - just bass sounds. The engineer for the session was Bob Woolford.

Interestingly, Bob Woolford was the engineer behind Incus, one of the world's leading free improvisation labels. He engineered Incus's first release, The Topography Of The Lungs, by Evan Parker, Derek Bailey, and Han Bennink. Woolford was also active in the Canterbury Scene, a term used loosely to describe improvisational music in that area that blended elements of jazz, rock, and psychedelia. He later engineered one of my favorites from that genre, Soft Machine's album Third, released in June 1970.

Phillips’ solo bass recording session took place on November 30, 1968. After the recording, Schubel was amazed and wanted to release it as a solo album. In an October 1984 interview with Coda magazine’s Bill Smith, Phillips shared:

After much hesitation and hair-pulling and soul searching I agreed to it and we edited it all up and there you are. That was a very strong moment for me, because basically I was playing everything I could think of to play, from all this stuff I'd been doing for years and years on the bass.

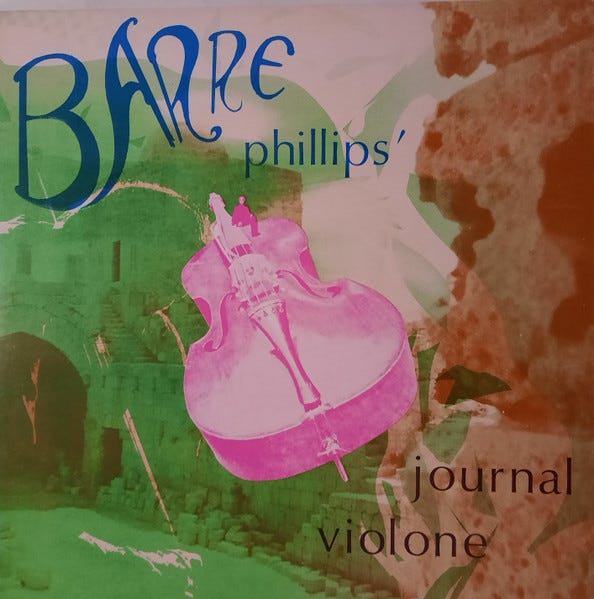

This was Phillips’ debut album and a masterpiece. Schubel released the album in the U.S. as Journal Violone, the second release on his new Opus One label:

Here is that entire album:

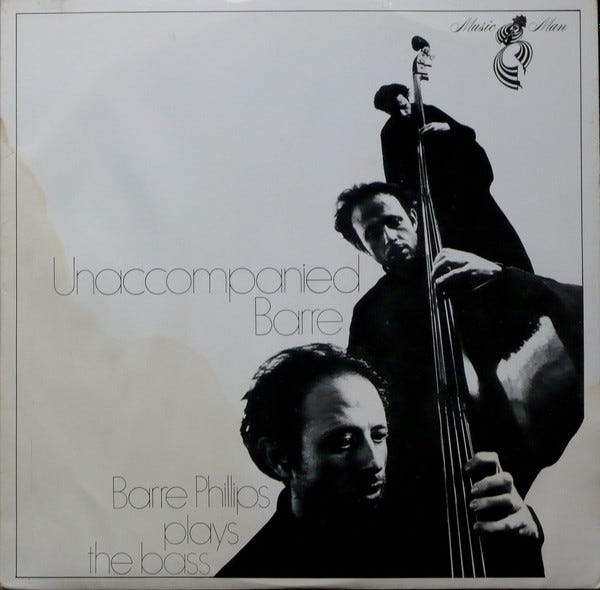

The recording came out the following year in the UK on the Music Man label as Unaccompanied Barre:

Schubel’s third release was Son Of Quashed Culch. The music was composed by Schubel with Alexander Kok on cello, cymbal, Averil Williams on flute, xylophone, gong, and Phillips on bass:

This session took place on January 2, 1969. It was also recorded at the Parish Church of St. James’ Norlands. Again, Woolford was the engineer.

In the fall of 1968, when Phillips travelled to London, he had not intended to stay. He was doing a little research, completely outside the music scene. However, after a couple of months, work was plentiful. He started playing with guys like Chris McGregor, Gunter Hampel, and the Spontaneous Music Ensemble. Soon, the creative work in Europe had replaced the more professional work he had been doing in New York City. Essentially, Phillips was finding more freedom with European musicians, who valued him more for his artistic expression rather than just a professional bass player who could do the job, as they did in New York City.

In October 1969, Phillips played his first gig with a new trio consisting of another American, Stu Martin on drums, and an Englishman, John Surman on horns. They called themselves The Trio.

The Trio’s first album was called simply The Trio. It was recorded in March 1970 in London and released by Dawn Records, Pye Records’ underground and progressive label. From that double album, here is Phillips’ smoking composition, Green Walnut:

During this time, on March 12, 1971, at Alster Film-Ton Studios in Hamburg, Phillips recorded For All It Is. The album was released in 1972 on the JAPO ("Jazz by Post"), a jazz album mail-order business started by Manfred Scheffner in Berlin in 1967:

This was one of the first albums Phillips recorded in continental Europe and features his compositions with American drummer Stu Martin and three excellent European bass players: Barry Guy (English), J.F. Jenny-Clarke (French), and Palle Danielsson (Swedish).

From that album, here is Y.M.:

It was in the European improvised music scene that Phillips flourished, and so he settled down in the South of France. This move symbolized the liberation of his music. In his words, “I was a two-headed person during the New York scene.” When he moved to the south of France, he considered himself a new musician, dedicated to playing improvised music.

Barre’s debut ECM recording was the history-making Music From Two Basses, recorded in February 1971 with Dave Holland. This was the first album released of mostly improvised bass duets.

In March 1976, Phillips reunited briefly with The Trio and, with the added effects of Dieter Feichtner’s synthesizer, recorded Mountainscapes at the Studio Bauer in Ludwigsburg, West Germany. It was released by ECM.

From the album, here is Phillips’ composition, Mountainscapes 4:

This is an excellent and underrated album. The final track is a nice bonus with John Abercrombie on guitar.

On November 14, 2024, on his Substack newsletter, Charlie Haden’s son Josh released a rare cassette tape titled Trio Basses 19-6-76:

This is terrific improvised music, and you can listen to the cassette here:

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Phillips continued recording in many different formats. For example, in 1998, he recorded an album with Joe Maneri and his son Mat. It was released in 1999 by ECM as Tales of Rohnlief:

From the album, here is Rohnlief - the spoken language at the beginning is completely made-up by Maneri, which I find very interesting and unique, sounding like some long-lost Viking dialect:

On May 23, 2003, Phillips, with bass players William Parker, Tetsu Saitoh, and Joelle Leandre, recorded a live performance at the 20th "Festival International De Musique Actuelle De Victoriaville” in Canada. It was released in 2004 by Les Disques Victo as After You Gone.

From that performance, here is PS-Te Queremos:

Another pioneering artist, Peter Kowald, passed away in 2002, and this release is a mournful requiem-like drone that truly honors the great German bassist, with whom in 1979 Phillips recorded Die Jungen: Random Generators on the FMP label.

Here’s one more for the road. In the summer of 2016, Phillips called Manfred Eicher to say he’d like to record a final solo album, to document “the last pages of a journal that began fifty years ago”. The result was End To End, simply a wonderful account of the art of solo bass. From that album, here is Quest (Pt. 2):

One thing I admire about Barre Phillips was his quest - his journey of discovery. In the liner notes of End to End, he recalls his time in the 1960s as a sideman back in New York City before he moved to Europe, “I started asking myself: is this your music now or not? What is your music? Am I on some road or other? Maybe I’m not a sideman anymore…” He confronted that no-man’s land between contemporary composition and improvisation. He broke free.

In 1980, Phillips told ECM’s Steve Lake, “It took four or five years until I discovered what it really was that got me going. I mean precisely what it was. And that was: sound. The sound of the bass.” Barre Phillips followed that sound, and it took him home. In the 1984 Coda magazine interview, Phillips shared:

Music is so much more than technique and knowledge and scales and this and that; it's the whole thing about life - and how do you teach that? Is it something that you want to teach?

I don’t think you can - it has to come from within.

Barre Phillips’ music and spirit inspired me and enriched my life. It has helped to take me home. For that, I will be forever grateful.

Next week on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig our paddles into the waters of Hans Reichel.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form, Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. To subscribe, please hit the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Until then, keep on walking….

One of those players whose presence guarantees the recording as worthwhile or more. I have a soft spot for The Trio's recordings. That "Son Of Quashed Culch" looks intriguing but I can't find an online sample anywhere, I may have to buy blind

I think “journal violone” was the second Opus One LP. The first was “Number 1” which appears to be a sampler. “Son of Quashed Culch” was third. But I could be wrong.