Artie Shaw

The trouble with Cinderella...

I played three chords for beauty’s sake and one to pay the rent.

-Artie Shaw

Artie Shaw was to me the hippest clarinetist in that he played it straight. His ideas would come straight out. He didn’t sound like he was studying from the book.

-Wayne Shorter

I first saw Artie Shaw in the 1970s while watching TV in the basement of the house I grew up in. He played a musician in H. C. Potter’s 1940 Paramount film Second Chorus, starring Fred Astaire, Paulette Goodard, and Burgess Meredith. Here’s a still from the movie:

Here’s a scene from the film featuring Shaw on clarinet playing Everything is Jumpin’ - - Dig Paulette Goodard’s line at the start: “Artie Shaw, who’s Artie Shaw?”:

When I saw the film, I didn’t know who Artie Shaw was. I thought he was just another Hollywood actor.

Many years passed before I understood that Artie Shaw was not just another Hollywood actor but a great jazzman and mysterious bandleader. Because he achieved his first major success two years after Goodman, and his musical career was intermittent, his contribution is often considered secondary to Goodman’s. However, I find warmth and creativity in Shaw’s work and think many of his recordings stand alongside the best jazz ever recorded.

This week on that Big River called Jazz we’ll dig in our paddles and explore the world of Artie Shaw.

In a 2013 Wall Street Journal article, American author and music critic Will Friedwald offered a good description of Artie Shaw:

[He] could be called the Miles Davis of the swing era—a restless artistic spirit who was driven to re-invent himself regularly, and the whole of jazz as a result. When he dramatically walked out on his own highly successful band in November 1939, it sent a shock wave through the entertainment industry. Yet when he reemerged four months later, leading a 25-piece orchestra with strings, it was even more of a revelation.

Born in 1910, Art Shaw left New Haven, Connecticut when he was 15 to tour as a jazz musician. He started his career at the Golden Pheasant in Cleveland, Ohio, with the Austin Wylie Orchestra. In Wylie’s band, he met Claude Thornhill and they became good friends. In 1929 Shaw and Thornhill left Wylie, traveled to California, and joined Irving Aaronson’s Commanders. After touring the country, they settled in New York City, where they worked as studio musicians. Shaw also played in Harlem jam sessions with Earl Hines and Jimmy Noone at the Apex Club and came under the influence of Willie "The Lion" Smith. He decided to stay in New York and at the age of 21 became one of the city’s most successful reed players for radio and recording sessions.

In 1932 he joined Roger Wolfe Kahn and his Orchestra and is seen here playing a clarinet solo at the start of the song:

In 1934 Shaw was part of Red Norvo’s Swing Septet and on September 26, 1934, he recorded Norvo’s I Surrender, Dear with some nice work by Jack Jenny on trombone. Norvo’s group also included Charlie Barnet on tenor sax and Teddy Wilson on piano:

Although Billie Holiday would join Shaw’s band in 1938, the actual starting point of the Shaw-Holiday musical relationship was probably a Vocalion recording session on July 10, 1936, the first for Holiday as a leader with her name printed on the record label under Billie Holiday & Her Orchestra. That band included Bunny Berigan on trumpet, Art Shaw on clarinet, Joe Bushkin on piano, Dick McDonough on guitar, Arthur ‘Pete’ Peterson on bass, and Cozy Cole on drums.

That recording session was a milestone in Holiday’s career, but it was just another recording date for Art Shaw, who was then a free-lance musician and in the process of organizing his first band built around of all things a string quartet. Here is No Regrets from that 1936 session:

I dig Shaw’s playing on this one. Interestingly, although Shaw was just a session man, he was enamored of Holiday and asked her to join his band. If that assertion is true, she probably laughed it off, not likely to join a band that didn’t even exist yet, led by someone she really didn’t know.

In 1936, after an all-star concert where he featured a small string section, Shaw was asked to perform at New York City’s Imperial Theater and formed his first big band called Art Shaw and his New Music. They recorded some minor hits for the Brunswick label, and his booking agent Tommy Rockwell landed them a nice gig at the Hotel Lexington in the summer of 1936. From that band here’s the scorcher Streamline, Recorded on December 23, 1936:

Shaw’s string approach was ahead of its time, but he was unhappy with the result. He disbanded it and the next year, following the example of Benny Goodman, set up a full-size conventional swing orchestra with three trumpets, two trombones, four saxes, and the standard four-man rhythm section. The new band settled into the Roseland-State Ballroom in Boston. It was there that Shaw finally got Billie Holiday to join his band after she left Count Basie in early March 1938.

In October, the band started their first big-time New York City gig at the Blue Room in the Hotel Lincoln, where Tommy Dorsey made his name, and Harry James got his start. Years later Shaw remarked, “I guess I had the healthiest attitude when I was first coming up. All I cared about was that the band sounded good to me.”

In New York City on July 24, 1938, Art Shaw and his Orchestra recorded his wonderful composition Any Old Time with “Billy” Holiday on vocals. Along with Holiday, Shaw’s band consisted of Chuck Peterson, John Best, and Claude Bowen on trumpet, George Arus, Ted Vesely, and Harry Rogers on trombone, Les Robinson and Hank Freeman on alto sax, Tony Pastor and Ron Perry on tenor sax, Lester Burness on piano, Al Lavola on guitar, Sid Weiss on bass, and Cliff Leeman on drums:

This would be her only recording session with Shaw and the RCA label. By November 1938 Holiday had left Shaw’s band and a month later Helen Forrest joined his band.

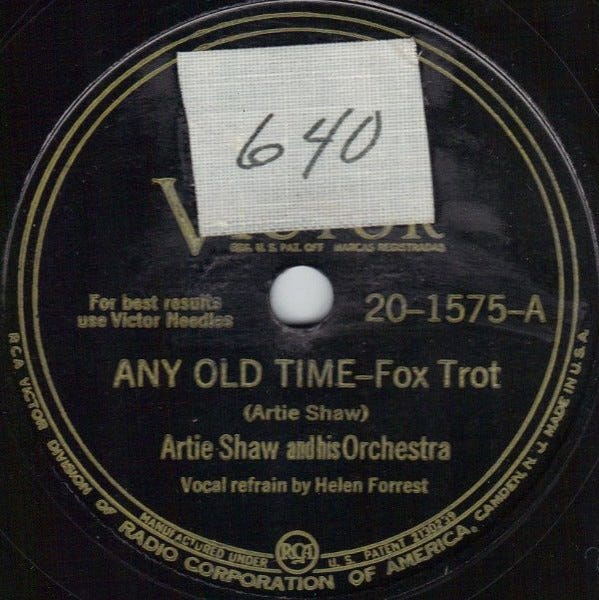

In 1939, Forrest recorded a new version of Any Old Time with Shaw’s band (by this time Shaw was no longer Art, he had become “Artie”):

Here is Helen Forrest’s version of Any Old Time:

Of these two versions, I think I like the Forrest version better. Forrest left Shaw in November 1939 and went on to stardom in the Benny Goodman and Harry James bands.

One of Shaw’s biggest hits was Cole Porter’s Begin the Beguine. The song was introduced in October 1935 by June Knight in the Broadway musical Jubilee at the Imperial Theatre in New York City. I wrote about Cole Porter here:

Shaw’s version of Begin the Beguine was recorded at the same July 24, 1938, session as Holiday’s Any Old Time. Here’s a wonderful video version of Begin the Beguine that shows the cool and debonair Artie Shaw at work:

By the way, that hard start at the beginning of the song was to get the attention of the dancers in the ballroom.

Interestingly, speaking of dancers, many years later when I first heard Shaw’s Begin the Beguine, I instantly recognized it from Norman Taurog’s MGM film The Broadway Melody of 1940, where the song was a prominent feature in the film, like this incredible tap dance by Fred Astaire and Eleanor Powell:

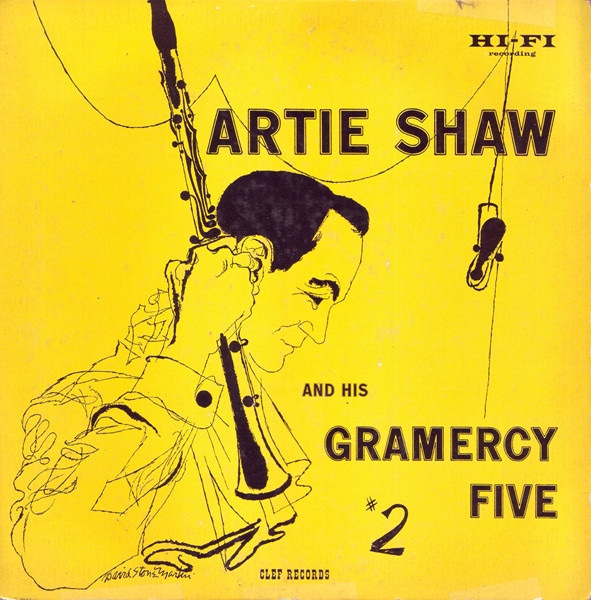

In the same vein as Ellington’s and Goodman’s small groups, Shaw configured his Gramercy 5 groups - a six-piece small group formed from his strongest jazz players. Shaw’s Gramercy 5 featured different line-ups while it ran between 1940 and 1954.

The 1945 version of his Gramercy 5 was a proto-modernist outfit that included trumpeter Roy Eldridge and two young boppers, pianist Dodo Marmarosa and guitarist Barney Kessel. Here’s a photo of that band:

Regarding Dodo Marmarosa, Shaw wrote:

It was a great band. Maybe my best. The dancers hated us, but the critics loved us. Along with the modern arrangements from Tadd Dameron and Johnny Mandel, we had to play all the old favorites like Begin the Beguine and Frenesi. One night we got three requests to play that tune. After the third time Dodo comes up to me and says, “If we play that tune again, I’m going to have to leave the band.” Sure enough the next night we got a request to play it and after we finished I looked over at the piano and no Dodo. That was the last time I ever saw him. His head was so full of musical ideas that it was hard to have a conversation with him, but I have the highest respect for his talent.

From that group here is Mysterioso, a harmonically advanced Shaw composition, not to be confused with Monk’s tune Misterioso:

In 1954 for his final Gramercy 5 recordings, Shaw put together what he felt was his strongest group, which I agree was his best. From those sessions here is a beautiful take on the Gershwin tune I’ve Got a Crush on You:

Dig Joe Roland’s cool vibes throughout. Shaw was exceptionally proud of these last recordings. In a 2002 interview, he shared this about his 1954 Gramercy 5 unit:

Well, I think I played better clarinet than I ever played before. I didn’t have any regard for the public and whether they liked it or didn’t like it. And I was playing with peers. I had a guy like Tal Farlow, a guy like Hank Jones, a guy like Tommy Potter on bass. They were all good players, and you had to play very well in order to be what you were.

In 1954, Norman Granz recorded this band on two 10” albums and released them on his Clef label with cool album cover art by David Stone Martin:

Here’s one more for the road. Artie Shaw’s music was innovative and influenced many other musicians. For example, British film score composer and singer Monty Norman’s 1962 James Bond Theme vamp seems influenced by Shaw's 1938 recording of his theme song Nightmare:

I hear the Bond theme in there. Incidentally, Martin Scorsese also used Shaw’s Nightmare throughout his 2005 film The Aviator.

In a 2017 Wall Street Journal article, Will Friedwald poignantly wrote:

The most familiar kind of tragedy in American music is that of the great artist who dies young, like Bix Beiderbecke or Charlie Parker. Then there’s the artist who does all of his major work only in the early part of his career, as critics once said of Louis Armstrong (though hardly anyone would agree with that assessment anymore). Artie Shaw represents a unique kind of cultural tragedy: the major artist who gives it all up at the peak of his powers for reasons that seem baffling to everybody else.

This strikes at the heart of Artie Shaw’s unpredictability. After those stellar 1954 Gramercy 5 sessions Shaw retired from music and focused primarily on writing. Besides his autobiography The Trouble with Cinderella: An Outline of Identity (1952), he also wrote two books of short stories I Love You, I Hate You, Drop Dead! Variations on a Theme (1965) and The Best of Intentions and Other Stories (1989).

It seems Artie Shaw both fought with and reembraced the band business. When his second band hit the top with Begin the Beguine, he disbanded and published an article describing the whole business as a “racket.” He moved to Mexico for a bit but less than a year later he was back and busier than ever. In a recent discussion with Northwoods Improvisers’ great bass player Mike Johnston, he shared this to help me better understand Shaw’s dilemma and the loneliness of our relationship with sound and music:

In its best moments [music] is personal, and you can feel vulnerable opening that up and sharing it. But, when you do it’s the best stuff and is real. That's what makes most great music not a commodity as it gets presented and marketed and it’s part of what I believe messes with musicians who are in fact doing that and not businesspeople.

I teach music history courses, and I strive to try to pull people's private journeys out of them that they've experienced with music. It's by far the most interesting stuff to read and have people share with you. If it's good, it's difficult to "grade" because that seems almost the wrong thing to do. It sort of commodifies personal experience.

In the end, Artie Shaw was asked to play too much dance music and that was not the world he wanted to inhabit - that did not make him feel alive. He was asked too often to play three chords to pay the rent and one for beauty’s sake. The problem is he was paying someone else’s rent - he didn’t need the money.

Next week, on that Big River called Jazz, we’ll dig in our paddles to explore the world of the winter solstice.

If you like so far what you’ve been reading and hearing on our journey and would like to share this with someone you think might be interested in learning more about our great American art form: Jazz, just hit the “Share” button.

From Astaire to Sun Ra: A Jazz Journey is a reader-supported publication. If you feel inclined, subscribe to my journey by hitting the “Subscribe now” button.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that.

Please hit this link to buy me a cup of coffee, if you’d like to show your guide some appreciation for this and past journeys. Know in advance that I thank you for your kindness and support.

Until then, keep on walking….

Thanks for the great introduction to Artie Shaw. His band's version of Begin the Beguine sounds like a perfect song. However, Mysterioso blew me away. Was it light years ahead of it's time? I wonder what the critics thought of it? On second thought, who cares what they thought. 🤘😎🤘