AACM

Great Black Music

There is an Afrikan proverb that says: "Children are the reward of life."

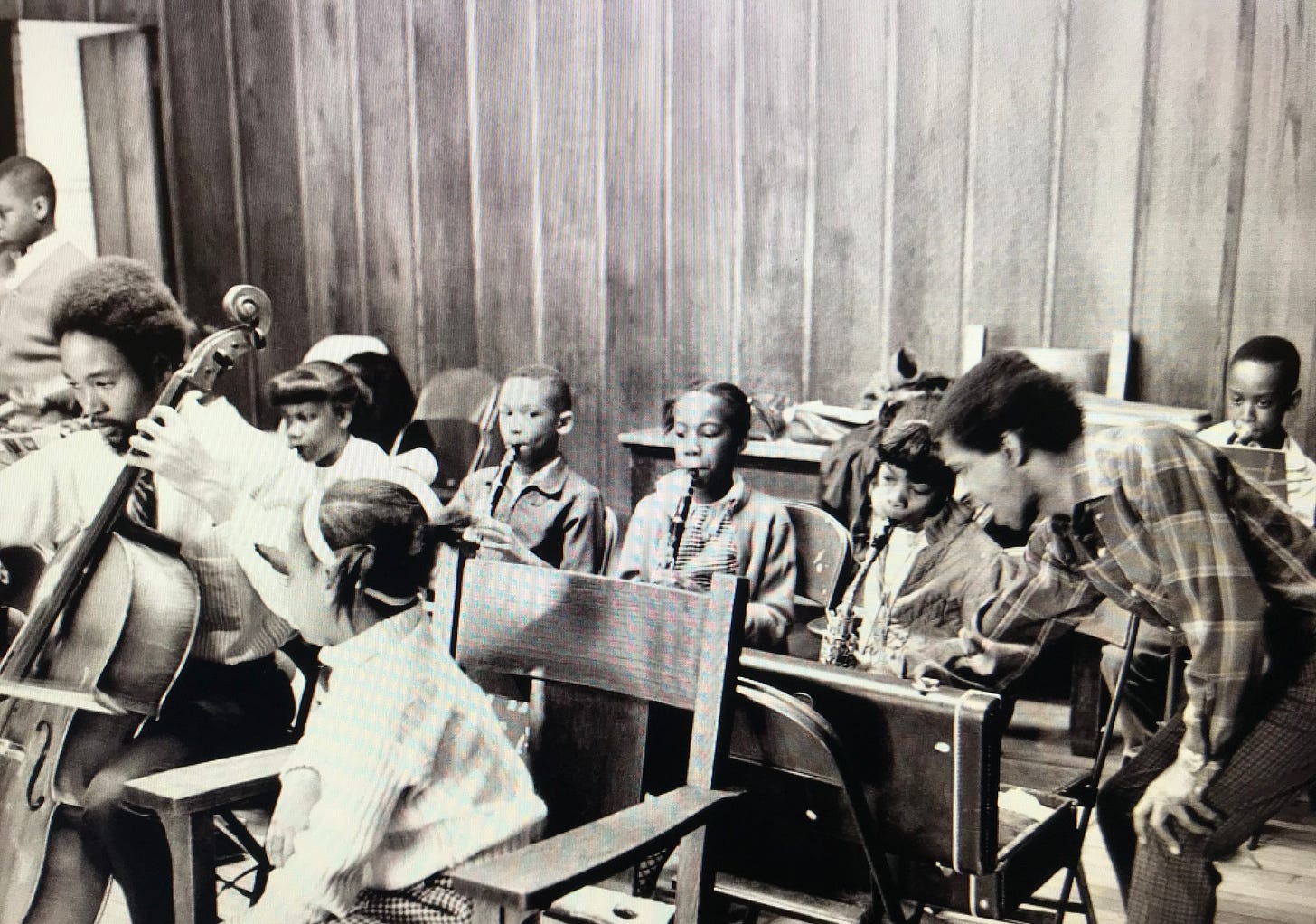

On the second floor of the South Shore United Methodist Church at 7350 South Jeffery Blvd. in Chicago, trombonist Steve Berry patiently teaches the movements of the instrument to Ester Spaulding, a pig-tailed 6-year-old who valiantly clutches the slide on an instrument that’s as tall as she is. She grapples with a mouthpiece that almost touches her nose.

By the front door of the church, young Brian Shelton waits impatiently for his parents to pull on their coats for the winter day. On his bulky parka is pinned a button proclaiming, “Great Black Music.”

In his hands, two drumsticks flail at the air. Brian, who has played at AACM concerts, is the youngest student in the school, yet he’s a veteran. He started taking classes when he was 5.

Flutist Douglas Ewart is explaining chromatic scales to the 13 children in his theory class, urging them to concentrate, chastising them when their attention wavers. He tells them, “Take it home and when you’re riding on the bus, study it. You fool around all day, well, study it on the bus. That’s how I did it.”

In another room of the church, Roscoe Mitchell holds an improvisation workshop. As a member of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, the most highly acclaimed group ever to emerge from the AACM, he is accorded something just short of star status.

Since its original members were organized by pianist Muhal Richard Abrams in 1965, the AACM has a long history of pioneering revolutionary ideas for jazz. They expanded its language by devising symbols, creating sounds never heard before, and raising the art of improvisation. But for the AACM, it was always about more than just music. It was about community, and they knew the heart of the community was the children. Three years after its founding, they opened up the AACM School of Music.

Amina Claudine Myers grew up in Roosevelt Heights, a neighborhood in south Dallas. She headed to Chicago to teach music to seventh and eighth-grade public school kids. After she started playing piano and organ at a church on Chicago’s West Side, she met Ajaramu Shelton, who was a member of this new organization called the AACM. She found her home there and joined in 1966, a few years before the AACM school was started. In an interview, she recalls:

“It was a beehive of activity. When I became a member I saw what everybody was doing, there was so much love there. Nobody criticized you, they were just encouraging and everyone was respective of the work you put out. Joseph (Jarman) was multi-theatre. And Roscoe, he had a cigar box he would carry around and he would ask you to contribute to the box. Then the next week he would give you something out of the box. I got a little skeleton on a keychain. Haha, I was gonna keep that forever!

They were doing everything in the AACM. You had to be brought in, you couldn’t just walk up and join. But I moved there to teach school and I was brought into the AACM by Ajaramu. He was a drummer and my boyfriend at the time and that’s when I started to wanting to move the music, open it up more. You get great joy just being free playing that music, trusting. Of course, you practice for technique. But then it’s most important to be open and let the spirit come through you. That’s what I learned in the AACM.”

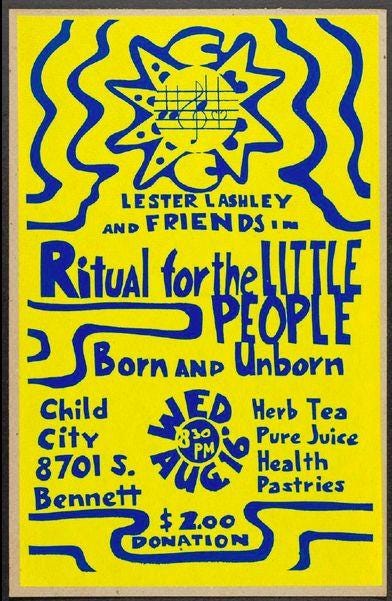

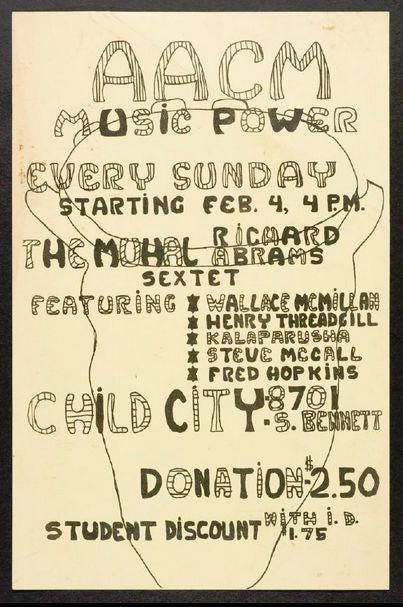

By the 1970s, Child City, located at 8701 South Bennett Avenue, now home to the Mayfair Academy of Fine Arts, was a daycare center run by AACM guitarist Pete Cosey’s mother. Child City was at the heart of much AACM activity and housed the AACM’s headquarters for a time. Child City has been described as a place filled with family, friends, and incredible experimental teaching and music-making.

Formed two years after Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, three years before his assassination, and in the same year as the Selma-Montgomery march, the AACM has clear ties to both King and the civil rights movement. Yet, instead of having to fight for their rights, the AACM asserted them from the very beginning. They weren’t waiting around and asking to be allowed in, but rather pushing to open the door, showing what was possible in the community and jazz.

And this is how they did it…

The Beginnings

Listen to this wonderful, short clip of Roscoe Mitchell talking about the AACM. No one can explain it better than him:

Here’s some of the music that came from the AACM community:

George Lewis, a second generation AACM member, has done an incredible job documenting the AACM and below I draw from his references.

In his book, A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music, George Lewis, writes about the early, pre-AACM beginning:

Eddie Harris told an interviewer in 1994. “Trying to play around Chicago, you figured there are guys that never played first chair, there are guys that never played on a big band, and there are other guys that never had an opportunity to write for a large number of people, and there are people that wanted to sing, and sing in front of a band—so let’s form a workshop.”

Harris credits trumpeter Johnny Hines as cofounder of the workshop, which at first attracted over one hundred musicians: “You start meeting guys, like the late Charles Stepney . . . There became a group of us. Muhal Richard Abrams, Raphael [Rafael] Garrett, James Slaughter, [drummer] Walter Perkins, Bill Lee. There was a small group of us who were on the same wavelength in trying things . . . not just sit down and play an Ellis Larkins run or a Duke Ellington run . . . we all wanted to try some different things.” The C&C Lounge provided a minimal but absolutely vital initial infrastructure for the musicians. Chicago trumpeter William Fielder, the brother of Alvin Fielder, recalls that “the C&C Lounge was a school for young musicians. Chuck and Claudia, his wife (C&C), offered the musicians a wonderful musical opportunity. The club would be empty and Chuck would say, ‘Play for me.’”

After Harris left to pursue his fortunes from Exodus to Jazz, the rehearsal ensemble soon dissipated, but a new ensemble, consisting largely of the younger players who were gathering around Abrams, started regular rehearsals at the C&C. The ensemble, which gradually came to be known as The Experimental Band, became a forum for Abrams to test his new, Schillinger-influenced compositional palette. Abrams recalls simply, “I just gathered together some people around me, some younger guys, and started to keep things going.” Two of these “younger guys,” saxophonists Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman, played critically important roles in what was later to become the AACM.

In his essay Experimental Music in Black and White: The AACM in New York, 1970-1985, which appeared in Current Musicology, nos. 71-73 (Spring 2001-Spring 2002), George Lewis discusses how a number of Chicago musicians received a postcard from four of their mid-career colleagues: pianists Jodie Christian and Richard Abrams, drummer Steve McCall, and trumpeter Philip Cohran, calling for a general meeting, and specifying fourteen issues to be discussed in relation to forming a new organization for musicians. The meeting was held on May 8, 1965, at Cohran's home on East 75th Street, near Cottage Grove Avenue on Chicago's South Side. The proceedings were conducted using more or less standard parliamentary procedure, and were recorded on audiotape. Each participant stated his or her name for identification purposes before speaking.

The participants were diverse in age, gender, and musical direction. Some of the meeting's participants had taken part in the rehearsals of Abrams's Experimental Band from 1961-64. Cohran in particular had found sustenance in the work of Sun Ra, with whom he had performed until Ra's departure for New York in 1961. Others were more traditional minded.

In the wide-ranging discussions in these early meetings, the musicians spoke frankly among themselves, rather than to any outside media. Already on display was the radical collective democracy that later became a central aspect of AACM ideology. What the taped evidence does not support, however, is the understandable but erroneous notion that the AACM was formed to merely promote or revise "new jazz," "the avant-garde," or "free music." Rather, with the very first order of business, the focus of the meeting was on finding ways to foster the creation and performance of a generalized notion of what they called "original music" or what later became: Great Black Music.

I include here some excerpts from discussions at that first meeting:

Richard Abrams: First of all, number one, there's original music, only. This will have to be voted and decided upon. I think it was agreed with Steve and Phil that what we meant is original music proceeding from the members in the organization.

Philip Cohran: I think the reason original music was put there first was because of all of our purposes of being here, this is the primary one. Because why else would we form an association? By us forming an association and promoting and taking over playing our own music, or playing music period, it's going to involve a great deal of sacrifice on each and every one of us. And I personally don't want to sacrifice, make any sacrifice for any standard music.

Steve McCall: We've all been talking about it among ourselves for a long time in general terms. We'll embellish as much as we can, but get to what you really feel because we're laying a foundation for something that will be permanent.

Melvin Jackson: Original music, I feel, is really based on the individual. It doesn't necessarily mean that I care to play all original music, which would be all my music.

Roscoe Mitchell: I think, you know, it's time for musicians to, you know, let go of other people and try to start, you know, finding themselves. Because everybody in this room here is creative. I mean, I think we should all try to go into ourselves and stretch out as far as we can, and do what we really want to do.

Gene Easton: The [post]cards originally said "creative music" and what picture I hold is that creative music can only be original anyway, in a true creative sense. "Original," in one sense, means something you write in the particular system that we're locked up with now in this society. We express ourselves in this system because it's what we learned, and if you don't express in the system that is known, you're ostracized. But as we learn more of other systems of music around the world we're getting closer to the music that our ancestors played-sound-conscious musicians, finding a complete new system that expresses us. Because there are far better systems, and I feel that we will be locked up for the rest of our days in this system unless we can get out of it through some means such as this.

Fred Berry: Now before we vote on whether or not we're going to play original music there has to be a clear-cut definition in everyone's mind of what original music is.

Richard Abrams: We're not going to agree on what exactly original music means to us. We'll have to limit now the word "original" to promotion of ourselves and our own material to benefit ourselves.

At the next meeting on May 15, the discussion evolved toward an exploration of how "original music" might interface with the venues and infrastructure system that these musicians were about to challenge and eventually outgrow:

Julian Priester: Taking into consideration economic factors involved, as musicians we're going to be working in front of the public, and different people, club owners or promoters ...

Richard Abrams: No, no, we're not working for club owners, no clubs. Not from this organization. This is strictly concerts. See, there's another thing about us functioning as full artistic musicians. We're not afforded that liberty in taverns. Everybody here knows that.

The new organization moved quickly to fashion a formal organization, with by-laws, offices such as president, vice-president, treasurer, recording secretary, business manager, and a board of directors. During meetings, a philosophy of collective, one person/one vote governance included debating procedures in which members were addressed as "Mrs.," "Mister," and "Miss." The first board of directors were: Floradine Geemes, Philip Cohran, Jodie Christian, Jerol Donavon, Peggy Abrams, and Richard Abrams. Sandra Lashley was charged with creating a name for the new group. And the rest is history.

Here’s a poster for a 1965 Experimental Band concert at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Abraham Lincoln Center in Chicago:

Here’s a more modern look at the Lincoln Center

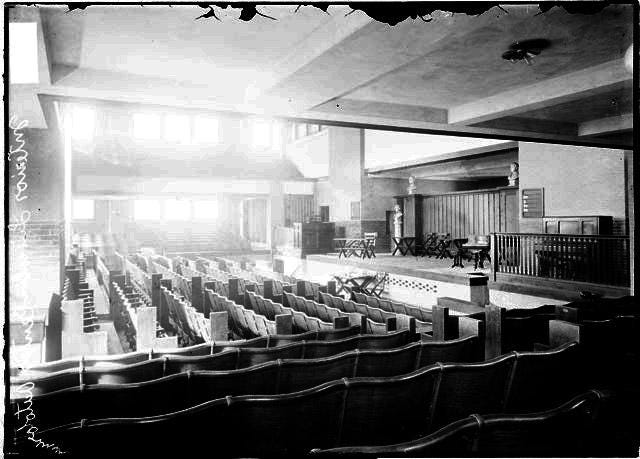

Here’s the interior of the building showing the stage.

and a photo from a 1967 AACM concert:

If you have an hour and a half, this is a must hear panel discussion with Roscoe Mitchell, Muhal Richard Abrams, Fred Berry and George Lewis at Stanford in 2014.

Sound

The AACM’s first album was recorded in August 1966. It has always been one of my favorites. According to Mitchell, "The musicians are free to make any sound they think will do, any sound that they hear at a particular time. That could be like somebody who felt like stomping on the floor... well, he would stomp on the floor. And you notice the approach of the musicians to their instruments is a little different from what one would normally hear... I always 'felt' a lot of instruments - and I feel myself being drawn to it. I'm getting more interested in music as strictly atmosphere, not so much of just standing up playing for playing's sake, but my mind stretches out to other things, like creating different sounds." That really sums up the ACCM’s definition of Great Black Music, which is very much NOT “Free Jazz”.

Chuck Nessa supervised the recording session and recalls that day: “August 10, 1966. Alto sax, trumpet, trombone, tenor, sax, bass, drums, cello, harmonica, alto recorder, and fruit juice cans filled with water - all causing recording engineers to worry. Six very confident young musicians go about the business of recording Roscoe Mitchell’s Sound, the first AACM music recorded for commercial consumption.” Here’s what that recording sounds like:

What I really like about this is how I find it often approaches a field recording, as presented by Chris Watson and Pierre Mariétan, who we’ll discover a little further down the river….

One more for the road….

Here’s another favorite from two early AACM members Eddie Harris on funky reeds and Muhal Richard Abrams on electric piano (buy the LP, it sounds sooo much better on vinyl). At the 9:00 minute mark this really soars to incredible heights:

The AACM school is still going strong - you can find them here

Next week, we’ll stay in the South Side of Chicago and explore the community that nurtured the AACM: Bronzeville.

If you like what you’ve been reading and hearing so far on our journey, please share my newsletter with others - just hit the “Share” button at the bottom of the page.

Also, find my playlist on Spotify: From Fred Astaire to Sun Ra.

Feel free to contact me at any time to talk shop. I welcome and encourage that….

Until then, keep on walking….